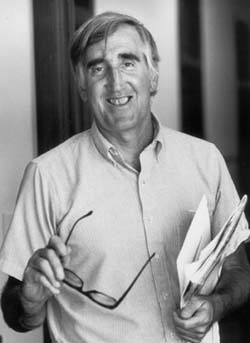

Larry Cuban Explores Good Schools in the Sachs Lectures

Larry Cuban, Professor Emeritus of Education at Stanford University, who teaches methods of teaching social studies, the history of school reform, and instruction and leadership, is the 2001 Sachs Lecturer. Cuban, Visiting Professor in Educational Leadership, will be concentrating on the question of "Why is it so hard to get good schools?" in his lecture series.

In an interview preceding his lecture on October 17, Cuban said, "I've been lucky. I've had two careers. As a practitioner, a teacher of social studies for 14 years, and as a school administrator, seven of which were spent as a superintendent. And then 20 years were spent being a scholar. I see myself as a practitioner and a scholar."

Prior to becoming a faculty member at Stanford, Cuban spent 14 years teaching high school social studies in urban schools, directing a teacher education program that prepared returning Peace Corps volunteers to teach in inner-city schools and serving seven years as a district superintendent.

Trained as a historian, he received his B.A. degree from the university of Pittsburgh in 1955 and his M.A. from Cleveland's Case-western Reserve University three years later. On completing his Ph.D. work at Stanford University, he assumed the superintendency of the Arlington, Virginia, Public Schools, a position he held until returning to Stanford in 1981.

His major research interests focus on the history of curriculum and instruction, educational leadership, school reform and the uses of technology in the classroom. Students at the School of Education have named him Teacher of the Year six times.

Some of his books include: Oversold and Underused: Computers in Schools; How Can I Fix It? Finding Solutions and Managing Dilemmas; Reconstructing the Common Good in Education: Managing Intractable Dilemmas (co-edited with Professor Dorothy Shipps); How Scholars Trumped Teachers: Change without Reform in University Curriculum, Teaching and Research, 1890-1990.

Speaking of his series of lectures, Cuban said, "All three lectures are built around the notion of good schools and why we have good schools-and the different kinds of good schools.

The first lecture, "Why Have American Schools Become an Arm of the Economy?" deals with why the business community, twice in this past century, has created one version of a good school that basically undermines all the different kinds of good schools."

"Twice in the past century, in vocational education at the end of the 19th early 20th century, and then in the past quarter century, ‘business-led coalitions' have basically converted public education into an arm of the economy. Because of fears of foreign competition public schools have basically taken on the singular goal of preparing students for the workplace. I argue with evidence that what has been created is a certain orthodoxy about what constitutes a good school in America. I also argue that we're living in the middle one of these orthodoxies right now."

Cuban explained his definition of "business-led coalitions." He said, "We're talking about a political coalition, of corporate leaders, public officials, unionists, and educators, who came together at the turn of the century, and said, ‘We have to have vocational education like the Germans do, or we're going to lose out in our products getting a share of the global market.' These were the 1890s and the introduction of vocational tracks in high school curricula-separate vocational schools-all with the notion of getting public schools to prepare people for the workplace."

"The coalition," Cuban added, "maintained the public schools were inefficient, in their governance, in their organization, and they had to become more efficient. These were the ‘efficiency progressives.'"

Since the late 1970's, he said, particularly since 1983 with the A Nation At Risk report, we've had another kind of coalition, made up of roughly the same kinds of people: corporate leaders, Fortune 500 companies, down to chamber of commerce, public officials, American presidents and governors, who demand that our schools have high academic standards-holding teachers, principals, and superintendents more accountable.

"In this most recent orthodoxy we have created a model of a 1950's traditional school, in which homework and high test scores are important, whether a student lives in Harlem or La Joya, California."

The second lecture, on October 29th, will lay out the different versions of good schools that we've had historically and contemporaneously.

The final lecture, on November 15th, will deal with this puzzle about why it is so hard to get good schools, and what type of schools we should have in a democracy.

Published Monday, May. 20, 2002