Power Principals

What's better than a principal who rises above the odds to achieve excellence in the New York City public school system?

How about 35 such principals-all pooling their thoughts and experiences over a 15-month period?

That's the premise of TC's Cahn Fellows Program for Distinguished New York City Principals. Launched in 2002, this unique program seeks to improve the city school system by-as funder and long-time TC friend Charles Cahn puts it- "recognizing, stimulating and further educating high-performing principals."

"Our approach is to encourage a culture of learning in the fellowship where all principals acknowledge that they have something of value to contribute and something of value to learn," says J. Kirsten Busch, the program's founding director. "This has allowed principals to confront their leadership challenges with their peers while forging a sense of community in the process."

The Fellows are organized into four working study groups to address leadership challenges they face in their schools. This year's groups are focused on student and staff empowerment and accountability, adult development, and organizational change. TC Professors Henry Levin, Victoria Marsick, and Leslie Siskin, and Harvard's Ellie Drago-Severson, are guiding the group's research and practice work.

The Fellows also participate in an intensive two-week Summer Leadership Institute at Teachers College that includes a trip to the Gettysburg battlefield to discuss how its history and the military strategies employed there relate to their profession.

To date, 35 New York City principals have completed the Cahn Fellows Program. Collectively, past and current Cahn Fellows serve over 40,000 elementary, middle and high school students in the five boroughs, but the program also seeks to improve the educational system for all the city's students. The Cahn Fellows meet periodically with New York City Schools Chancellor Joel Klein, and also mentor selected new principals, known as the Cahn Allies.

One Day at aTime

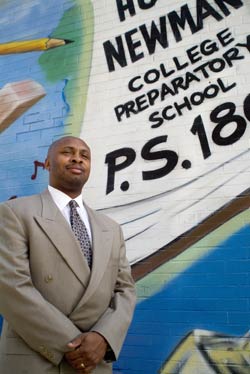

Star principal Peter McFarlane has led an effort to turn P.S. 180 from one of the worst-performing elementary schools in the city into a place where kids can start on the path to college.

As Peter McFarlane, principal of P.S. 180, walks the hallways of his school each morning, people wave, shake his hand or ask him how it's going. To which he unfailingly answers, "I'm struggling." McFarlane's high energy and warm smile provide thecrucial context: Here, in a Harlem elementary school the New York Times once named the city's worst, it's always a struggle to give the 445 students inside a better education. But it's a struggle the school is winning, and McFarlane is at the center of it all.

As a film major who worked in advertising, McFarlane might seem an unlikely candidate for this role. Still, he's paid his dues in the school system, from teaching at his alma mater, P.S. 128, to working as a research assistant for a special education coordinator. He also loves a challenge-and in 1995, when he arrived as principal, P.S. 180 more than fit the bill. Prior to his arrival, nine people had preceded him in the job, each cycling through "just long enough to get something on their resume and move on." Even as recently as 1999, not a single child at P.S. 180 passed the standardized reading tests and only 14 percent passed in math. The physical plant was dilapidated, and the entire school only had about 15 computers.

Fortunately, McFarlane had had some very direct preparation for the job. While a doctoral student at Teachers College, working with Thomas Sobol and Margaret T. Orr on issues of school improvement, McFarlane had joined a team of P.S. 180 faculty and staff who were trying to turn the school around.

"I learned there are four crucial steps to improving a school," he says. "Aligning its curriculum with standards, employing the best teachers, engaging in professional development, and building a community."

There has been significant progress on all these fronts during McFarlane's tenure. To name just a few of the highlights: 83 percent of his fourth graders scored at or above grade level on this year's citywide tests; the school recently secured a $1.1 million grant to improve an athletic field; and P.S. 180 was chosen as one of five Harlem schools to participate in the $50 million Say Yes to Education scholarship. And in September, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg called McFarlane "a star," adding, "The way he has turned his school around and given his students the foundation in learning, and the confidence that they are all on their way to college is a microcosm of what we need to achieve throughout the city."

McFarlane is quick to credit his faculty and staff for that success. He also says the Cahn Felllowship has helped him in a number of ways, from bridging academic research and practice, to exposing him to peers who bring fresh perspectives to the role of principal. "When you're around great people, you want to be great," he says.

So what's the next trick up McFarlane's sleeve? He wants to vanish (though not like his nine predecessors) by "distributing leadership" - that is, further empowering his staff to make decisions.

"You need to listen and learn from your colleagues because they have a wealth of knowledge to bring to the table," he says. "A lot of principals forget they're in this position because they're learners themselves." Not that McFarlane is one to stay removed from staff or students. After a morning of greeting, checking on students and pressing various organizations to help his school, he picks up a broom and starts cleaning up the cafeteria after the receding fifth graders. No one bats an eye.

"This is where I gather my head together," he says. "I get some of my best ideas here."

What drives him? That's simple: "When I got here, we had kids in the upper grades who were born here but couldn't read or write English. How can we let that happen in America?" He pauses to share a smile with a tall fifth-grade girl lining up for the next lunch period, and he moves on. The struggle continues.

Teaching on Principal

What's the secret behind the success of one of the city's best intermediate schools? The boss has had a little classroom experience.

In a time where we use fridges and phones, people may not realize that "principal" is an abridgment of "principal teacher." If so, they haven't met Janet Lynch-Aravena. Aravena has taught math in New York City schools for the past 29 years, continuing her classroom work even when she was named principal of the Hudson Cliffs School (P.S./I.S. 187), near Fort Tryon Park in northern Manhattan. Only this year, after five years in her "new" job, has she given up a regular class schedule to focus on projects such as mentoring principals. Still, she says, "my bookbags are ready at the door."

Teaching informs all aspects of her job, Aravena says, and you can see it in her laser-like focus on Hudson Cliffs' 835 students as she walks through the halls of the school. She has an easy but firm way with kids, whether she's fixing the collars of the kindergartners or checking the schedules of the 8th graders. Students' spines straighten when she enters a classroom, but she doesn't hesitate to mix it up with them-checking their progress or helping with group activities. "My favorite moment in this job," she says, "is when you go into the classroom and the children welcome you and want to talk to you about what they're learning and why they're learning it. It makes me smile, because it's what educating is all about."

Even outside the classroom, her background has helped her to be an effective administrator, particularly in dealing with her staff. "The teachers thought it was wonderful that I was a teaching principal," she says. Instead of being aloof, "I was sitting next to math teachers in their conferences, learning and growing along with them." She has used this familiarity to focus on teacher empowerment, creating what she feels is a stable organizational structure. "If I'm not in the building, everything still works like clockwork," she said. "As a leader, that makes me very proud."

With the ship that steady, the administration has had room to try some novel solutions to challenges. For example, after a recent wave of teacher retirements left P.S./I.S. 187 with more than 20 percent of its teachers in their first or second year, the school began using experienced teachers and even retirees to mentor the rookies. The result: significant gains in teacher performance and retention rates.

But Aravena isn't one to rest on her laurels-and that's where the Cahn Fellowship has come in. Her project as a Fellow is to facilitate the transfer of best practices in teaching. "I believe the culture of teaching has made teachers uncomfortable with sharing their practices, and I want to make that more open," she says. She's offered tours to other principals who are eager to see the workings of one of the city's best intermediate schools, and has started research centered on "learning walks," under the guidance of Teachers College professor Henry Levin.

"When you've been in the business for as many years as I have, you're constantly reflective, but the Cahn Fellowship has brought me to the next level," she says. "It's given me the opportunity to be part of a network of successful educators and allowed me to learn and share best practices. And that's made me more confident."

Published Tuesday, Apr. 12, 2005