Filed Under > TC People

Chartering Newark's Future

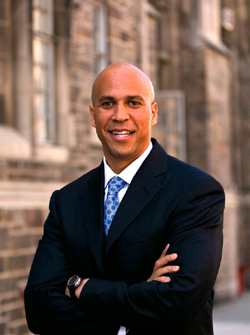

TC Trustee Cory Booker has made Brick City a much safer place, but his legacy there may rest on how much he can improve the schools

One night during Cory Booker’s eight-year stay in Brick Towers, a Newark housing project notorious for its drug dealers and violence, he came upon a 12-year-old boy named Wasim Miller who had been shot four times in the chest. Speaking in 2006 at Teachers College, where he is a trustee, Booker, who had just become Newark’s mayor, recalled that horrific experience:

“He fell backwards, and I caught him. I remember laying him down on the ground and watching his chest fill up with deep, red blood. I drew my hands into this boy’s chest, trying to stop the bleeding, and screaming at people to call an ambulance, call the police, asking his name, and when I got it, saying, ‘Wasim, don’t go, stay with me.’ He coughed and gagged and went silent, and I tried to clear an air passage, but he died.

“And I remember going home that night and giving up. I was so angry and so frustrated at the world, I just could not understand why this could happen—why, in a nation that professes to stand for what we stand for, would we allow this kind of reality to exist?”

After a sleepless night, Booker walked outside and spotted Virginia Jones, Brick Towers’ indomitable tenant president. He knew she had lost her own son, a soldier, to gun violence in Brick Towers while he was home visiting her on leave. Just seeing her snapped Booker out of his funk.

“I had asked her, not long after it happened, ‘Mrs. Jones, why do you live here?’” Booker recounted. “’Why do you choose to stay here in Brick Towers, where we’re both paying market rent, when there are so many other places you could live?’ And she looked at me, and she drew herself up and folded her arms across her chest, and she said, ‘Because I am in charge of Homeland Security.’”

An American Story

On a beautiful Saturday in early spring last year, a crowd had assembled for the reopening of a block-long, wedge-shaped park in Newark’s North Ward where George Washington and his troops rested in 1775. Most of the city council members were there, particularly those from the largely Latino North Ward, where Booker has always been popular with voters.

Some time before noon, the Mayor, flanked by aides in suits but wearing a short-sleeved shirt and sneakers, rolled up in a black van, jumped out and began shaking hands and hoisting children on his shoulders. Not long afterward there was an Easter Egg hunt, with Booker presiding. The winner, a little girl named Natalie, shyly collected her prize, a bicycle, then turned to run back to her family.

“Hey, where you going?” Booker called after her, grinning. “You gotta learn to be like a politician and always stay for the picture.”

The story of Cory Booker and his crusade to transform one of America’s most benighted cities has perhaps been more widely chronicled than that of any other modern-day politician. Booker’s first mayoral bid, when he lost to the incumbent Sharpe James in 2002 by just 3,500 votes, became the subject of the award-winning documentary Street Fight. His first year in office was the focus of a 10-part series in the New York Times, and more recently, he and members of his administration were real-life characters in “Brick City,” a docudrama on the Sundance Channel that was co-produced by the actor Forest Whitaker. He has been featured in a host of major publications.

Booker has star power, to be sure. He is just 41, black, strikingly handsome, a former high school football All-American (and All-Pacific-10), Rhodes Scholar and Yale law school graduate. He quotes scripture, Langston Hughes and Elie Wiesel. He has recruited show business personalities like Brad Pitt, Bon Jovi and Sarah Silverman to help Newark, not to mention hedge fund managers, intellectuals and wealthy philanthropists. And he has guts, shrugging aside an assassination plot by the New Jersey chapter of the Bloods after his victorious 2006 mayoral campaign.

He has needed all those assets as Mayor of Newark, a city he calls “the center of the fight for America.” Twenty-six percent of Newark’s 280,000 people live in poverty, and in some neighborhoods more than 40 percent, a level many experts view as the threshold for collapse. Unemployment, by official tally, stands near 15 percent, and as of the 2000 census, little more than half of Newark’s working-age adults held jobs or were looking for work.

The Newark public school system was so dysfunctional that in 1995 the state took it over and still retains control. Only one in 11 adults in Newark holds a college degree, among the nation’s lowest rates of college attainment.

Corruption has pervaded the city’s politics, with five of the past six mayors, including James, having been indicted during or after they were in office.

And then there is crime. Until the past two years, during which Booker and his police chief, Garry McCarthy, have presided over the nation’s most dramatic reduction in homicides and shootings, the city was among America’s most violent.

But it may be his obsession with accountability that best explains Booker’s grip on the popular imagination.

“I’m a Christian man who loves Judaism, because I love this idea of wrestling with God,” says Booker, who was elected to lead a Jewish student organization at Oxford. “And I love my own heritage, because there were people who believed that you never, never give up the fight.”

Similarly, at TC’s 2009 commencement ceremonies, he exhorted graduates to “Be the change you want to see”—a standard even his critics usually credit him for genuinely trying to meet. “He doesn’t have to be here,” a member of Newark’s school board told me last spring. “He could be running a hedge fund.”

Taking the hard way

Yet even before completing his Yale law degree, Booker, who grew up in the affluent New Jersey suburb of Harrington Park, had relocated to Brick Towers in Newark and took jobs as a staff attorney for the Urban Justice Center and program coordinator of the Newark Youth Project.

A political career may already have been on his mind, but there surely were easier ways to earn his street cred. In 1999, as a councilman representing the city’s Central Ward, Booker waged a 10-day hunger strike to protest police indifference to gang violence, sleeping in a tent across from another Newark housing project where just a few weeks earlier the security booth had been burned to the ground and the guards forced to flee by drug dealers. Later, he lived for five months in a trailer, parking each night on other blighted corners. Local gangs threw garbage and excrement at him, and other members of the city council denounced him for pulling a publicity stunt, but he stayed, leading neighborhood vigils that ultimately brought a public visit from Mayor James. Back in Brick Towers, he led a legal fight against the landlord that resulted in successful federal prosecution. The Democratic Leadership Council, Bill Clinton’s power base, named him as one of their “100 to Watch.”

As Mayor, Booker didn’t change his M.O., holding open office hours during which the public could meet with him personally to discuss everything from parking tickets to eviction notices. (These continue on a bimonthly basis.) He stayed in Brick Towers for several more months, part of a last group of tenants who held out against the demolition of the complex until a deal was struck to replace it with a better facility. He worked 14-hour days and spent his weekend nights riding out with the police to the scenes of shootings, declaring repeatedly that his administration would live or die based on its performance on public safety.

Meanwhile, the Booker team was directing $40 million through a public/private partnership to upgrade more than 20 parks and playgrounds; doubling construction of affordable housing; deploying 100 new surveillance cameras and 140 new police officers; creating programs to find jobs for ex-offenders; and creating a $6-million fund to support small business development.

These efforts have by and large earned Booker high marks from many close observers on the Newark scene.

“The biggest, most overwhelming challenge Cory Booker faced when he was elected was the perception of Newark as a nearly failed city—and, in some people’s minds, as a city that had already failed,” says Rutgers University historian Clement Price, who chairs the Newark Public Schools Foundation. “That was a huge challenge, and across the board, that’s been his greatest success—that through his personal magnetism and persuasiveness, he has encouraged a lot of people inside and outside Newark to give it a second or even a third chance to succeed as a city. Because of him, a lot of people—and I include myself as one of them—now see it as a city that has turned a corner and can be saved.”

Booker has his critics, too, particularly regarding unemployment, which has increased sharply during the economic downturn of the past two years, compounding the city’s persistent intergenerational poverty. Some—Price included —feel he should not have been part of the “Brick City” docudrama or a facetious on-air feud with Conan O’Brien. Booker is still considered a virtual lock to win reelection this June against Clifford Minor, an Essex County prosecutor who is backed by Sharpe James, but there is some speculation that turnout at the polls could be underwhelming. “The country has been in the grip of a tenacious recession for two years, and Newark has felt the pain,” Price says. “People could take out their idiosyncratic frustrations against Cory by voting for Cliff.”

A legacy in education

If public safety has been the bellwether for Booker’s first administration, education may well dictate the success of his second one and tell the ultimate tale of his legacy to the city. Booker has intimated as much from the beginning of his time in office, making it clear, in that same 2006 speech at Teachers College, that he understood Virginia Jones’ reference to “homeland security” in a broad context.

“I went to a conference where Colin Powell was talking about the Middle East, and at one point I raised my hand and asked him what he considered the biggest threat to our national safety,” he told his audience that day. “And he didn’t miss a beat. He said poverty and the education achievement gap. And I thought, ‘Wow, this guy really gets it.’”

Booker has repeatedly asserted that he would not only like Newark to regain control of its school system, but also that he wants the kind of mayoral control of schools achieved by Michael Bloomberg (New York City), Richard M. Daley (Chicago), Adrian Fenty (Washington, D.C.) and Thomas Menino (Boston). However, to win back local control of their schools, New Jersey municipalities must successfully navigate a murky process known as QSAC (for “Quality Single Accountability Continuum”)—a series of repeated evaluations that must culminate in a city meeting at least 80 percent of criteria in five categories just to become eligible. Then, when the state decides to give the go-ahead, the city must hold a referendum within the next 365 days to determine whether its school board will be an elected one or, instead, appointed by the Mayor.

To date, Jersey City is New Jersey’s only municipality to regain control of its school system from the state, and while Newark is expected to follow suit at some point during the next few years, no one is holding their breath.

For Booker, that’s essentially left charter schools as the one venue through which he can improve education opportunities for the city’s young people.

“I’ve become sort of the Malcolm X of education,” he said in an interview conducted at TC after he spoke at the College’s 2009 commencement. “Which is, by any means necessary we’re going to get there. And I’m not going to be an ideologue about this. I don’t think that charter schools are, by definition, good. I don’t think that public schools are, by definition, good. I don’t think that private schools are, by definition, good. The only good schools I know are the ones that produce good results. And I’ve got 45,000 school-aged children in Newark that I feel responsible for, even though I don’t run the schools. And I’m going to find a way to get great educational options for every single one of those children.”

Only the state can actually grant charters, but Booker has done everything in his power to create a receptive climate for charters in Newark.

During his first term, seven charter schools have either opened or expanded in Newark, with the number of students in charters increasing from about 3,500 to 6,400, or about 14 percent of the overall student population. Booker ultimately hopes to increase that figure to as much as 25 percent. He has laid the groundwork for that expansion by brokering the establishment of the Newark Charter School Fund, a coalition of four major national foundations—Gates, Walton, Fisher and Robertson—that has invested $18 million. Four local foundations—Victoria, Prudential, GEM and MJC Amelior have also signed on, committing another $4 million for future projects. Thanks to the creation of the Fund, two leading charter school organizations, KIPP and North Star, have pledged to open as many as 18 new schools in Newark over the next decade.

Largely through the Fund, the city also has signed contracts with several “non-traditional” organizations that prepare teachers and school leaders, including Teach for America, Building Excellent Schools, New Teachers for New Schools and the New Teacher Project, to create what Booker calls “a pipeline of human capital” into the schools. Last year, the Fund covered the full cost of each certified teacher placed in a district or charter school in Newark, and also covered the full cost of the one-year residencies required for teachers brought in by Building Excellent Schools and New Leaders for New Schools.

Most recently, the city and the Newark Charter School Fund have partnered with a private developer, Ron Beit, on an agreement for a project called Teacher Village, which will create three new charter schools—including one led by KIPP and another by Discovery, another successful group—and on-site housing for teachers across an eight-block downtown area in the Central Ward.

With New Jersey’s recent election of a Republican, Chris Christie, as Governor, and with Christie’s appointment of Bret Schundler—formerly Mayor of Jersey City, and an outspoken proponent of school choice—as state education commissioner, the long-term outlook for charter school development seems especially bright. Newark, too, has a new schools superintendent—former Washington, D.C., schools chief Clifford Janey—and he is much more open to charter school development than his predecessor.

But what really makes school development in Newark unique is that, ultimately, it is not all or even primarily about charters. Indeed, that was the city’s pitch to the four national foundations now represented in the Newark Charter School Fund.

“They had pooled their resources to prove that you could create a vibrant, highly successful charter sector to sit beside and hopefully help a traditional district,” says De’Shawn Wright, Booker’s top education advisor. “They had looked at the top 100 urban environments with charters and decided which would be most ready for significant investment, and initially they decided on Newark, Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. And we said to them, great, we support what you want—the Mayor does not see charters as a universal panacea, he believes a majority of kids will always be in traditional public school districts. But Newark is the only place to do it. Because in New Orleans, the charter sector is completely replacing the public school sector, which was essentially wiped out in Hurricane Katrina. And in D.C., 40 percent of their kids are already in charters, and they’ve been so aggressive about it that those schools are mirroring the traditional public schools. The kids are faring about the same. But Newark, in part because the state has been so stringent about approving charters, has a smaller number of charters and they’ve been doing a great job.”

Similarly, the Teacher Village complex will house teachers from both charters and traditional district schools, and the deal with the alternative teacher preparation organizations will provide teachers for Newark’s district schools as well as for charters.

“We said, the last thing we want is for there to be a fight for talent, and the district has to benefit from the influx of high-quality educators from this,” Wright says. “The superintendent didn’t have the resources to invest in it, so the Fund covered 100 percent of the first year for him.” Ultimately, Wright says, the city doesn’t care whether these new teachers end up in charters or district schools. “As long as you’re in a Newark school, our investment is paying off.”

Once a Brick Citizen…

Booker’s quest for mayoral control of Newark’s schools highlights perhaps the biggest question people have about him.

“I don’t think people are worried about him having mayoral control—it’s a question of who will come after him,” says Dan Gohl, Executive Officer for Innovation and Change serving under Newark’s schools superintendent.

It will take another four years, and perhaps longer, to judge the sum of Cory Booker’s accomplishments in Newark. There are those who feel that if, as he has indicated, he moves on after two terms in office, it will mean that the job was only a way station in his career. Perhaps they are grudgingly expressing the fear that, however unsatisfying life has been, the specter of a Newark without the idealism and energy of Cory Booker is a lot more frightening. By the same token, it’s hard to imagine Booker without the city he has made his personal quest.

“I feel like Newark has given me the greatest blessings of my life, beyond my family,” he said last year. “Newark is often called ‘Brick City.’ And people think it’s because of the architecture, but I always say it’s because of the people. That they’re strong, they’re hard, they’re resilient, they’re enduring. And when folks come together in Newark—like bricks—there’s nothing they can’t build or create. And so to have the chance to work on a daily basis with this spirit, it’s a gift.”

Published Wednesday, May. 19, 2010