Playing It Forward

Mary Skipper believes schools need to work together to succeed. She has a fan in the White House

Mary Skipper believes schools need to work together to succeed.

She has a fan in the White House

By Joe Levine

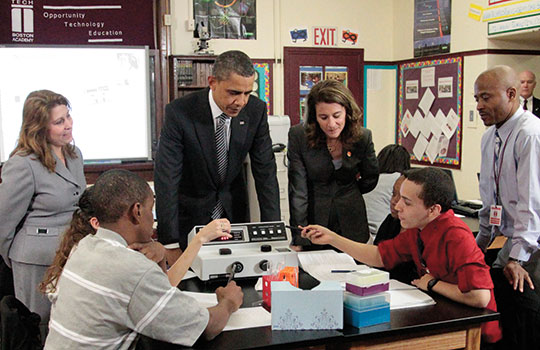

When President Obama visited TechBoston Academy this past March, he singled out founding Principal Mary Skipper for special praise.

Speaking to an audience of teachers, students and visiting dignitaries, Obama called the Academy, a high-achieving school in one of Boston’s poorest neighborhoods, “a model for what’s happening all across the country,” and added, “at the helm is Mary Skipper, who is doing unbelievable work. Love ya, Skip!”

It was a moment that any school leader would have savored. But for Skipper, a doctoral student in TC’s Urban Education Leaders Program, the day’s real highlight came later, when Obama cited TechBoston as an antidote to the nation’s educational inequities. “The motto of this school is, ‘We rise and fall together,’” the President said. “Well, that is true of America as well.”

“That really made my day,” Skipper, a petite, blond-haired woman of 43, said afterward. “It’s going to be the opening line of my dissertation.”

“Working together” may sound corny or superficial, but in Skipper’s hands, it’s a sophisticated entrepreneurial strategy that may indeed represent the best hope for improving the nation’s educational system in an increasingly cash-strapped era. The basic idea: schools too often function as isolated units striving only for their own success. They end up competing against one another for scarce resources instead of looking for ways to share in-house expertise—which costs districts money and penalizes students.

The antidote, which Skipper is detailing in her dissertation, is a systems-focused approach to leadership in urban school districts, centering on promoting collaborations between high-achieving schools and under-performing ones.

“In Europe there’s a real framework for working that way,” says Skipper, who attended a conference in China in 2006 with 100 other principals from around the world, led by David Hopkins, an architect of the United Kingdom’s widely admired systems approach. “But in the U.S. it’s kind of a fresh concept.”

But not totally unheard of. In 1998, Skipper and a colleague, Felicia Vargas, built a special unit within the Boston public school system that was dedicated to introducing advanced technology courses to schools across the city. Called simply “Tech Boston”—as distinct from “TechBoston Academy,” the school—it offered high school students professional-level certification in software programs such as Microsoft Office, Adobe Products and Cisco Networking. On the most immediate level, that enabled teenagers to command office wages of $25 per hour and up—but they weren’t just learning secretarial skills.

“We all think we know Microsoft Office, but most of us know about a tenth of what the program can really do,” Skipper says. “Professional certification puts you in a whole different league.”

Students learned graphic and Web design, certified network administrator skills and computer programming code. They also heard talks from representatives of industry partners—including Microsoft, Cisco, Intel, Apple, Adobe, Lexmark and Hewlett-Packard—about the kinds of opportunities a college degree opens up in their companies.

“We were particularly trying to reach kids at risk for dropping out,” Skipper says. “They were highly intelligent, but they didn’t see the purpose of school—the connection to the next thing. We were showing it to them.”

From an initial cohort of 20, the unit created by Skipper and Vargas grew to 2,000 students and 100 teachers at 10 Boston high schools and 15 middle schools. Skipper says that every student in the first cohort graduated from college and is now working in a job related to science, math or technology.

Skipper moved on from that work, creating TechBoston Academy in 2002 with a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. She weathered a bout with breast cancer, and the city nearly scotched the project because funding was tight, but today, the Academy is one of Boston’s top-performers, boasting a graduation rate nearly 20 points higher than the citywide average. Last year, 94 percent of the senior class headed off to college—most of them the first in their families to do so.

The secret? “We hire quality teachers who are certified in multiple specialties and are committed to lifelong learning,” Skipper says. Also, as head of a pilot school, Skipper has autonomy over curriculum and schedule. Technology obviously is a piece of the puzzle, too: the school, which equips every student with a laptop, offers the same kind of software certification programs as Skipper’s system-wide initiative. It also maintains a consulting group that hires students out to do real-world work, such as building Websites for local businesses, and a “job shadow” program that enables them to see what an engineer does, or a biomedical technician, or a computer scientist.

Skipper sees that kind of collaboration—with external partners—as another critically important strategy for creating system-wide success.

“If schools can offer corporate partners something in return, those companies are going to put down local roots,” she says. “It starts with giving them insight into why they’re not getting employees who can do the things they need, but it extends to convincing them that as a district or a city, you’re committed to education and technology and the kind of work they do. That’s why Google is committing resources to Kansas City right now, and it’s what we did with the companies we worked with in Boston.”

Ultimately, Skipper hopes to employ a systems-based approach from the vantage point of being a superintendent herself—not in a big city, but perhaps in a district of about 50,000 students, where she can stay focused on instructional issues rather than politics. Her advisor at TC, Carolyn Riehl, believes she is precisely the kind of person to take on that role.

“Mary is so bright and quick, and she’s already got such great experience under her belt,” Riehl says. “It’s typical of her to focus on an approach in which the advantaged help the less advantaged. That’s who she is in everything she does. It’s a real challenge for a university to add value for students like that.”

Back in March, President Obama seemed to agree.

“It used to be that we weren’t sure what worked to help struggling students,” he told his audience at TechBoston. But now, he said, there’s a growing consensus that “what’s needed is higher standards and higher expectations; more time in the classroom and greater focus on subjects like math and science” and “outstanding teachers and leaders like Skip. And all of those ingredients are present here at TechBoston.”

For her part, Skipper has been mulling over one of the particularly good ripples from the President’s visit.

“A lot of our middle school kids who met him and shook his hand passed on the handshake to their friends—and they, in turn, passed it on to other kids,” she says. “It went on for weeks. And that’s exactly what schools need to do with their knowledge base—they’ve got to pass it on to other schools.”

Published Thursday, May. 19, 2011