Filed Under > Research/Publications

Eating Smarter

When patients relearn the seeming innate act of swallowing, their brains change -- and their lives can, too

Since suffering a stroke the previous January, Forrester had been unable to swallow food or drink without choking (the condition called dysphagia). He was being fed through a tube in his stomach, but he missed eating, especially jerk chicken and fish, specialties of his native Jamaica.

Now, after four weeks of trial therapy, Forrester was being reevaluated by Amy Ishkanian and Carly Weinreb, master’s degree students in TC’s Speech-Language Pathology program, which runs the Mysak Clinic. After performing some other tests, Ishkanian and Weinreb gave Forrester a few sips of water. He sputtered a little but got it down. They used a small, balloonlike device on the end of a tube to test Forrester’s tongue strength, and they pronounced his progress good. They swabbed different flavors – sweet, salty, sour and bitter – on his tongue, and he identified each. They checked his gag reflex and air flow – again, all signs positive. They asked him to repeat the word buttercup as quickly as he could, and he complied, until they all broke into giggles.

Georgia Malandraki, Assistant Professor of Speech-Language Pathology, who spearheads TC’s new swallowing therapy program, says that Forrester and four other patients in a pilot project at Mysak have all “improved remarkably” in their ability to swallow. But it’s what may be going on in their brains that she finds truly exciting.

In the small, utilitarian space on the ninth floor of Thorndike Hall that she established last year as TC’s Swallowing, Voice and Neuroimaging Laboratory, Malandraki has been analyzing functional magnetic resonance images (fMRIs) of the brains of dysphagia patients who participated in a postdoctoral research project she conducted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison under the direction of swallowing researcher JoAnne Robbins. Like Joseph Forrester, some of the patients in that project performed regular tongue exercises over an eight-week period in order to restore tongue strength diminished by stroke or other brain injury.

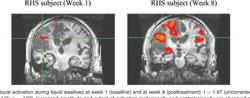

Initial images taken before the patients began their exercise regimen showed large brain areas where there was little to no neural activity. But images retaken halfway through the trial, and again at the conclusion, showed increasingly large multicolored splotches, indicating more brain activity (see images on pages 42 and 43). Malandraki says the results, which have been submitted for publication at the 2013 International Stroke Conference, appear to offer the field’s first true confirmation of what has long been suspected and hoped: Muscle exercises not only improve muscular function, but also can stimulate neuroplasticity – the actual rebuilding of injured areas of the brain or the transfer of brain functions to healthy areas.

“Nobody has ever shown before that swallowing strengthening therapy can lead to neuroplasticity,” Malandraki says.

Swallowing disorders are on the rise, and the demand for therapy is growing rapidly.

As advances in health care and nutrition enable people to live longer, rates of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other disorders that disproportionately affect the elderly have risen dramatically, and many of these conditions trigger dysphagia. Indeed, of all patients seen by speech-language pathologists in hospitals, nursing homes and rehabilitation centers last year, more than half received swallowing therapy, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. In New York City alone, up to 90 percent of patients seen by speech-language pathologists in acute-care facilities have swallowing disorders.

Many dysphagia patients lose their cough reflex, putting them in danger of aspirating food or liquid into the lungs and developing pneumonia or dying. While feeding tubes offer an alternative, they are expensive and inconvenient and raise the risk of infection. Moreover, eating is one of the few remaining pleasures for the frail elderly, and Malandraki and other experts say that many of those who lose the ability to eat lose their appetite and their will to go on living, as well.

More than 35 muscle pairs are involved in swallowing, including most of those involved in speech. Like all muscles above the neck, they are connected directly to the brain stem by cranial nerves that bypass the spine. Until the 1970s, doctors believed that the swallowing reflex is innate and governed largely by the autonomic nervous system. They believed that, although swallowing can be intentional, the throat muscles mostly work like the heart, which beats continuously without conscious direction from the brain. It was thought that someone who had lost the ability to swallow could never recover it.

By the early 1980s, Martin W. Donner at Johns Hopkins and, later, Jerilynn A. Logemann at Northwestern University (who has been Malandraki’s collaborator) and other researchers began to understand swallowing as a more complex, coordinated activity performed by muscles in the mouth, throat and esophagus that activates different parts of the brain. Their research led to a new hypothesis: By exercising these swallowing muscles, patients were transferring function to new brain regions.

In recent years, a range of technologies have made it possible to pinpoint which neurons come into play under different conditions and in response to different stimuli, enabling researchers to correlate observed behavior with brain function and development. The Dysphagia Research Clinic in the Mysak Clinic is newly equipped with many of these technologies, including high-quality fiber-optic endoscopes, which are used for the evaluation and diagnosis of swallowing physiology; electromyography (EMG), which is used for evaluation of the electrical activity produced by swallowing muscles; respiratory biofeedback and muscle-strengthening devices; and sensory stimulation equipment and materials.

Currently, Malandraki is working with doctors and therapists at Columbia Medical Center who treat patients with dysphagia caused by head and neck cancer. Using fMRI technology, she evaluates candidates for trans-oral robotic surgery, which can remove the tumors without an incision to the neck or throat, and measures how the tumors have affected swallowing physiology and brain function before and after surgery. Malandraki started the project in 2011 with Salvatore Caruana, Chief of Head and Neck Surgery at Columbia Medical Center, backed by a grant from TC’s Provost’s Investment Fund. The team, which includes Robert De La Paz, Columbia’s Director of Neuroradiology, and TC alumnus Winston Cheng, Chief Speech Pathologist, is attempting to raise more money to establish a swallowing and neuroimaging center at Columbia.

Meanwhile, Joseph Forrester has continued to come regularly to the clinic and to do his assigned tongue and neck exercises at home. By early October, he had made further progress in swallowing and tongue strength and had resumed eating many of his favorite foods. He had even gone, unescorted, to a friend’s house and eaten his beloved jerk chicken. The swallowing therapy at the Dysphagia Research Clinic “has given him his independence back,” says his son, Jason Forrester.

As of this writing, the elder Forrester was still using the feeding tube in his stomach to ingest water, a challenging substance for patients with dysphagia, but there was hope that the tube could be taken out in a few months. “When my father first had his stroke, the initial concern was the length of time, efficacy and danger of infection using the feeding tube,” Jason Forrester says. “That’s not something we’re even speaking about now.”

Link to: Fox Health News Features TC's Swallowing Clinic

Published Friday, Dec. 7, 2012