Filed Under > TC People

Dreaming Local

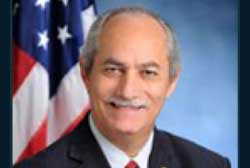

Guillermo Linares (Ed.D., '05) is leading the fight to make undocumented immigrant students eligible for state financial aid

By Siddhartha Mitter

On Sherman Avenue, just off of West 207th Street in Inwood, staff members in the district office of State Assemblyman Guillermo Linares (Ed.D., ‘05) greet constituents who drop by with a polite “Como está ustéd?”

“I’m trying to make myself Mr. Immigrant in the state Legislature,” says Linares, who represents the northernmost part of Manhattan.

That goal might seem obvious for New York City’s former Commissioner of Immigrant Affairs, but Linares nowadays is training his sights on a very specific goal: passage of the proposed New York State Dream Act, for which he is the lead sponsor in the Assembly.

“The Dream Act is the most important piece of legislation for me,” says Linares, who spoke at TC this past spring, along with the Act's co-sponsor, New York State Senator Bill Perkins, in a panel titled The New York State DREAM Act: Educational Equity for Undocumented New Yorkers." (Watch the videotape of the event below.) In the version under consideration in New York State, the measure would make undocumented immigrant students eligible for state financial aid for higher education.

NYS DREAM Act: Educational Equity for Undocumented New Yorkers