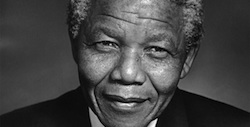

Mandela Remembered

Following Nelson Mandela's death on Dec. 5th, several Teachers College faculty members shared their reflections on the great South African leader and fighter against racism and apartheid.

Edmund W. Gordon, Jr., Richard March Hoe Professor of Psychology and Education

How fortunate the world is to have had among us for 95 years one Nelson Mandela!

We mourn his having died, but we should celebrate forever that he lived -- and the way in which he lived his life: with great dignity, personal integrity, respect for all of humankind, and a universal commitment to economic and social justice.

Janice S. Robinson, Vice President, Diversity and Community Affairs

There are insufficient words to describe the depth and breadth of the global changes Nelson Mandela brought forth. Despite being labeled and jailed as a terrorist, he led a successful movement for freedom and democracy. In November 1994, I was in South Africa lecturing at the University of Witwatersrand. It was just a few months after Mr. Mandela was elected president. There was still euphoria in the air despite the realities of the decades-long complex societal transformation that lay ahead. That work still remains today. I pray it continues to be addressed with the wisdom and non-violence of President Nelson Mandela.

Morton Deutsch, Professor Emeritus, Psychology and Education, and founder of TC’s International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution

I consider Mandela the most impressive leader of our time. His life provides important lessons for all of us in managing difficulties and conflict. There are two that I would like to emphasize:

- Despite the difficulties and hardships one has to confront, never give up hope and embrace cynicism. Despite many years of imprisonment, Mandela continued to hope that he could improve the world and he acted upon that hope whenever he could do so.

- Even during the course of bitter conflict do not view your adversaries as inhuman, not entitled to justice and care. Mandela, despite his horrible treatment by his adversaries, did not seek revenge when he came in power. Rather he sought to include them in an integrated, just society.

George Bond, William F. Russell Professor of Anthropology and Education

In human history there are few great men, especially in post-colonial states. The late Nelson Mandela was one of them. He was a man of the people and stood firmly for the basic principles of justice and equality for everyone, whether African or European, Asian or American. His past was one of struggle; his present was to honor and preserve the rights of us all.

I remember the day he was imprisoned. I was a student at the London School of Economics, and a group of us – the West African students and the few black Americans – were in the refectory when a fellow whose father was Prime Minister of a West African country made the announcement. We were devastated by the news; we were wondering when he would get out.

Of course, it took years. But when he did, he laid down the principles for an open, free and democratic South Africa. He structured and anchored a non-racial society and preserved the non-racial dimensions of justice. He collaborated with F.W. de Klerk [South Africa’s white president], a brilliant effort that many thought would explode, but which ended in peace. The white South Africans are African, too, and to exclude them or penalize them as white or as “Europeans” would have been the same as saying, in this country, that African-Americans are Africans, not Americans.

Perhaps as important as anything else, Mandela retired with grace.

Thus, we acknowledge his profound contributions. But now we must look to the future. We must be vigilant in protecting and preserving all that Nelson Mandela stood for. Now that he is dead we must strive to maintain his legacy as an active force in history.

Peter Coleman, Professor of Psychology and Education, Director of TC’s International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution *

Nelson Mandela, one of our world’s great leaders, was a man of many contradictions. Born the son of a village community leader, he developed an abiding respect for authority. Yet he spent decades of his life fighting doggedly against pro-Apartheid state authorities in South Africa. Having had consensus-based decision-making modeled for him by his father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, a local chief and councilor to the monarch, he learned to listen, facilitate, collaborate and unite. But having trained as a boxer and a trial lawyer, he also developed as a tenacious fighter, spending hours every day training his body and mind to be strong, disciplined and overpowering.

Years later Mandela became a leader of the African National Congress and shared their core value of non-violence. He was a master at methods of non-cooperation and civil disobedience, organizing scores of nation-wide mass marches and stay-at-home protests. But when these strategies failed and were met with brutal violence on the streets from government forces, he went underground for two years to start a militant wing of his party, and studied military strategy, munitions, sabotage and guerilla warfare. Yet Mandela had the foresight to target the use of violence against things not people; realizing that the destruction of objects like energy grids, bridges and communications towers – things that could make the country ungovernable – would be less alienating and consequential to South Africans and the international community than the annihilation of human beings.

Mandela was later incarcerated on Robben Island and served as a political prisoner for twenty-seven years. While in prison, he developed the fine arts of jujitsu tactics, learning to leverage his low position of power by using the rules and laws of the authorities to bring about their own undoing. He studied the prison handbook and committed the rules to memory and then would cite them chapter and verse and use them to control the actions of the more violent guards. However, he also quietly built relationships of rapport with many of his guards, learning of their personal circumstances and the names of their children. When he was eventually approached by the Afrikaner government of President Botha, who instigated negotiations over the terms of his release, Mandela bargained tenaciously, even choosing to stay at the table when he learned that the government was simultaneously attempting to derail his party, the ANC, by providing their enemies in the Inkatha Freedom Party with weapons. Later, when elected President of South Africa in 1990, Mandela displayed the compassion, grace and benevolence of a truly great human being – reaching out to unite all of the people of his fractured and damaged nation.

Mandela employed all of these seemingly contradictory competencies and strategies – as convener and boxer, non-violent activist and violent militant, empowered prisoner and embattled president – over the course of his decades-long struggle against Apartheid and journey towards a united, democratic, multiethnic South Africa. He needed them all to adapt to a rapidly changing world and to change the world for the better. He needed them to lead.

*excerpted from Coleman’s September 2011 piece, The Mandela Doctrine: Lessons for Obama, which appeared in The Huffington Post

Published Monday, Dec. 9, 2013