Lost in Translation

The United States is becoming a majority non-white nation. To truly level the playing field, non-whites will need to reclaim and recast their own narratives.

The United States is becoming a majority non-white nation. To truly level the playing field, non-whites will need to reclaim and recast their own narratives.

By Elizabeth Dwoskin

As a four-year-old arriving in the United States from Peru, Cyndi Bendezú-Palomino (M.A. ’13) saw her mother detained at the Mexican border. She lived through Proposition 187 (which was later overturned), which would have prevented all undocumented students from attending California’s public schools. She passed up a scholarship and a prestigious internship because she lacked a social security number.

“I got really depressed,” recalls Bendezú-Palomino. “I was angry at the system, but I blamed my parents, too, because I didn’t know who else to blame.”

In summer 2010, Bendezú-Palomino helped to mount a civil disobedience campaign to urge passage of the federal DREAM Act, which would create a path to citizenship for many undocumented immigrants who complete two years of postsecondary education or armed forces service. The Dreamers, as the organizers call themselves, lost that fight but successfully pressed President Obama to sign a memo enabling many undocumented youth to obtain a two-year work authorization and a stay of deportation.

“It was a big moment for us,” says Bendezú-Palomino, who is now a permanent resident. “Obama needed the Latino vote. We weren’t afraid anymore.”

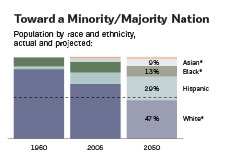

By 2043, whites will constitute less than half the population in the United States. In public schools, the tipping point is just five years away. The historical moment echoes the late 19th century, when Teachers College was founded to equip teachers to work with students from diverse backgrounds and cultures. Then as now, the country was absorbing waves of immigration, and many blacks were migrating from the post-Civil War South to northern cities.

Today the nation has its first black President, and Latinos and other groups are flexing increased political muscle. Yet other barriers must fall in the law, health care, language policy and education before these groups can win equal standing in American society.

At TC, many believe that the heart of that work has to do with telling stories.

“A huge part of being an immigrant and coming from an immigrant culture is the passing of oral traditions,” says Jondou Chen (Ph.D. ’12), whose parents came to the United States from Taiwan as graduate students. “A student tells the story of his mom telling him the story of what it was like to grow up in China during World War II. She told it to him while they were flying to the U.S. It brought tears to their eyes, and it still does.”

As with all diasporas, from the exile and dispersion of the Jews to the relocation of Africans through slavery, such stories memorialize not only “how we got here” but also “who we were.” The ideal of the melting pot has given way to that of the hyphenated American who draws strength from a sense of difference.

Two years ago, Chen led a project by TC’s Student Press Initiative (SPI) in which recent immigrants at special New York City high schools wrote personal histories. SPI staff interviewed the students in languages ranging from Mandarin to Gujarti and the students then wrote (and rewrote) essays from the transcripts. Their pieces were anthologized in Speaking Worlds: Oral Histories from GED-Plus.

“Those students might be judged as cognitively delayed because they hadn’t yet received a high school diploma and were above the age one is supposed to receive it,” says Chen, now a staff researcher with TC’s National Center for Children and Families. “But they have rich life histories and many are deeply reflective, so why not turn what’s seen as a deficit into a strength?”

Hope Leichter, TC’s Elbenwood Professor of Education, similarly argues for the power of family memories as a source of “creative intelligence for how to overcome hardship, adapt strategies employed in a different time and place to life in this country today and resist discrimination.”

At the Elbenwood Center, Leichter teaches courses on “The Family as Educator” and “Education in Community Settings: Museums.”

“There’s a plaque in Grace Dodge Hall that talks about ‘the ennobling arts of the home’ being taught to coming generations,” Leichter says. “At the Elbenwood Center, we’re looking at the modern version of the ennobling arts. How do we juggle work, family, community? Many of our grandparents and parents did it under more difficult and dangerous circumstances.”

Such stories also offer teachers a critical window into students’ minds.

“Difference in classroom communication styles is one of the biggest sources of misunderstandings,” says Derald Wing Sue, Professor of Psychology and Education. “For too long teachers have subscribed to negative stereotypes, such as ‘Asian students are too quiet’ or ‘African-American students are aggressive.’” These often unintended “microaggressions” can lower students’ self-esteem and hurt their academic performance.

Stories of shared experience not only transform a group’s own perception of itself, but others’ perceptions as well.

“Social construction of local histories is crucial in the process of domination and subjugation by rulers of those they rule,” writes George Bond, TC’s William F. Russell Professor of Anthropology and Education. “Authority and legitimacy are conjoined through the fabrication, inscription and recitation of historical narratives and are an essential part of governance.”

The corollary, Bond says, is that colonized people – whether tribes in Africa or blacks in the United States – must revise societal narratives to assume their own identity.

“Blacks within the U.S. have always been demeaned by other people,” says Bond, whose father and uncle were among more than 200 black intellectuals who earned their Ph.D.’s and conducted research with support from the Rosenwald Fund, a scholarship program created by the founder of Sears Roebuck and Company. Other beneficiaries included the poet Langston Hughes, the pan-Africanist W.E.B. DuBois and the political scientist Ralph Bunche. “Blacks have stuck as units to their families, hailed the accomplishments of their families. So I stand with my father, his brothers, my mother, my sisters, my cousins. So that if you write about me, I would like it to be contextualized.”

Younger African Americans fight similar battles, but they can draw upon role models like Bond.

“African Americans are not thought to value achievement, and when they do achieve, it’s seen as the exception,” says David Johns (MA ’06), Executive Director of the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans. “But we can look to history and sociology to identify the way in which people like James Baldwin and Richard Wright offer reimagined understandings of the very complex and complicated social beings we are.”

Members of other ethnic groups wrestle with the same underlying issues.

“The stereotype of the ‘model minority’ mistakenly assumes Asian immigrants can succeed in this country,” says Hong Kong-born Vanessa Li (M.A. ’11), who worked with teens in Chinatown while completing her degree. In reality, Li says, many Asian Americans who were professionals before immigrating work in restaurants and factories because of language barriers. Their children often drop out of high school to help support the family. “The biggest issue for me was helping Asian teens with their self-esteem.”

Michelle Knight, Associate Professor of Education and an expert on critical race theory, argues for formal curricula that provide the “reimagined understandings” cited by Johns.

“Cultural awareness of African Americans and a culturally responsive curriculum rooted in African-American traditions have been cited as solutions to some of the structural barriers that first-generation African-American students encounter in schools,” Knight writes. Such curricula could help offset the “loss of hope for a bright future” and the perception of “a hostile atmosphere” that many first-generation prospective black students feel when visiting predominantly white colleges and universities.

Often such curricula exist, but institutions need to make them visible. Thus Regina Cortina, Associate Professor of Education, established TC’s Latina/o and Latin American Faculty Working Group in 2007. Faculty and students share their research and have created an online resource for TC research on Latinos (www.tc.edu/latino-ed). They also have argued for more aggressive recruitment and enrollment of – and increased financial aid for – Latino students.

“We need to train teachers and leaders who can serve predominantly Latino communities and schools,” Cortina says. “TC has the bilingual/bicultural programs in education, school psychology and speech pathology,” as well as the concentration in Latina/o and Latin American education that Cortina directs.

Narratives aren’t only stories or curricula. Consider the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which defines the conditions that caregivers treat and that health insurers cover. Among the 52 examples of stresses listed in DSM-IV, race was not mentioned and discrimination was noted only once.

To Robert Carter, Professor of Psychology and Education, that absence negates the everyday experience of minorities. Carter’s research has convinced him that people experience nightmares, depression and physical ailments following abrupt or repeated incidents in which they are belittled or harmed due to race. Yet, he says, “You have to go through hell if you bring a claim for racial harassment.”

The barriers facing minorities in America can seem monolithic. But Hope Leichter believes change may begin to accelerate. “A generation of children was born with the current president in office,” she says. “I don’t mean to suggest that just because we have a black president, all racial problems have gone away. But for these children, this will be the baseline for what is normal.”

U.S. school systems are producing the nation’s most racially diverse generation. Some prejudices and stereotypes will disappear, Leichter says, as young people build on childhood friendships, choose careers and, especially, inter-marry.

“The increase in mixed marriages and mixed-race children is a tremendously hopeful development,” she says. “Ultimately all racial categories are social constructions. The more we mix, the more those constructions and the limits they impose are likely to fall away.”

In May, Cyndi Bendezú-Palomino received an M.A. from TC’s Higher and Postsecondary Education program, becoming the first member of her family to graduate from a master’s program in the United States. “My parents and family are the reason why I am here today,” she says. “They left their own country, families and lives to come here, where they were constantly exploited but always worked with dignity. And just to give us an opportunity to pursue higher education.”

Published Thursday, Jun. 13, 2013