Filed Under > Research/Publications

Learning By Doing, Even When He Can't Do Much

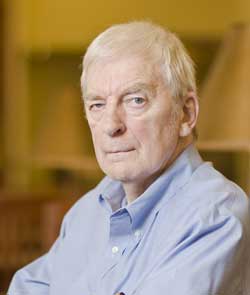

Former TC Professor Tom Sobol has been confined to his bed for the past three years, but his new memoir is about the fullness of life

By Joe Levine

The page that precedes Tom Sobol’s introduction to his memoir, My Life In School, is blank save for what appears to be an inked fingerprint. It’s an appropriate symbol for an author who was limited to typing with just one finger – Sobol, who suffers from a spinal cord disorder, has been confined to his bed for the past three years and was wheelchair-bound long before that – but the symbolism may have broader intention.

My Life In School does, in fact, chronicle the nearly 80 years that Sobol has spent in education – including an eventful eight-year tenure as New York State’s Commissioner of Education, when he ended up siding with plaintiffs from New York City who were suing the state for more education funding. But his real focus is on the kind of learning that disciples of John Dewey like to call “hands-on.”

In the book’s opening pages, Sobol recalls playing next to a creek behind his family’s home in Malden, Massachusetts, undeterred by warnings from his mother and aunt that a little boy had recently drowned there.

“The back and forth of the water made a powerful impact on me…Later on, grown-ups would explain about the moon and the tides, and I would try to get all that into my head. But all I really knew was that something very wonderful was happening, and I felt I was part of it.”

In the story that follows, Sobol – who retired as TC’s Christian A. Johnson Professor of Outstanding Practice in 2006 – repeatedly wades up to his neck into what he has elsewhere described as “life’s messiness.” In prose reminiscent of Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, he describes how, at age 12, he cooked meals and cared for his two younger brothers when his mother abruptly left the family for a year. He chronicles his escape from his tough Irish Catholic neighborhood through Jewish friends who led him to the prestigious Boston Public Latin School, which served as his springboard to Harvard. And with both an unsparing self-scrutiny and a penchant for literary allusion that will be familiar to anyone who took his law and ethics courses at TC, Sobol ponders his own moral choices.

“In church, I grew up with the language of Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer,” Sobol writes. “His cadence and poetry in English is stunning. How often I have recited in church, ‘We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done.’ If you read such prayers aloud, or hear them read aloud, year after year, throughout your most formative years, the texts gain a resonance that becomes part of your linguistic DNA.”

You can hear Cranmer in Sobol’s thoughts when he reflects on his conduct during three-year stint in Army counter-intelligence in Korea, where one of his assignments was to learn about the nation’s thriving prostitution industry.

“I got to know many girls and to talk to people who were part of that life,” he writes. “Young and healthy as I was, I never slept with any of them. I don’t know why I didn’t. I wondered about it then, and I’ve wondered about it in retrospect ever since. I don’t know whether it was morality, because I was married, or whether it was timidity, because I was young and relatively inexperienced. I don’t know whether I didn’t because I was strong, or I didn’t because I was immature. But for whatever reason, I didn’t.”

And Cranmer feels very much present in perhaps the most riveting section of My Life In School, in which Sobol recounts his harrowing induction as New York State’s Commissioner of Education. It was the job he’d long coveted, but the circumstances quickly turned nightmarish: the New York State legislature’s Black and Puerto Rican Caucus launched an all-out protest against his appointment, charging that the State’s Board of Regents had broken its promise to choose a person of color. (The Regents had originally offered the position to an African American who had turned it down.)

The controversy became a media story that wouldn’t die, and Sobol was only saved when Governor Mario Cuomo called a press conference and spoke on his behalf. But then came the backlash from the opposite quarter: Sobol immediately appointed four committees to investigate education issues affecting minorities and make recommendations about how to fix them. When their reports came in a few months later, Sobol, ignoring the advice of aides, went public with the results – and soon found himself the focus of a New York Post editorial titled “Sobol’s War on Western Values,” which accused him of issuing pronouncements that sounded “more and more as if they were written by Angela Davis.” It got so bad that at one afternoon, Sobol couldn’t work up the nerve to leave his Albany office to go out lunch. He thought about going home, but in the end, he writes, “Something stronger than public embarrassment wouldn’t let me go.”

Above all, Sobol savors the richness of life and the value of experience as a teacher. There is never a sense of a man writing under the house arrest imposed by his physical infirmity – never a note of self-pity, or any suggestion that he has ceased to “learn by doing,” or to enjoy learning, even though he can no longer do very much. In a speech of his that he includes in the book’s appendix, Sobol harks back to the neighborhood creek of his boyhood with an excerpt from Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, in which Water Rat takes Mole sculling on the river.

“Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats,” Water Rat says. “Nothing seems really to matter, that’s the charm of it. Whether you get away, or whether you don’t; whether you arrive at your destination or whether you reach somewhere else, or whether you never get anywhere at all, you’re always busy and you never do anything in particular; and when you’ve done it there’s always something else to do, and you can do it if you like, but you’d much better not.”

To which Sobol appends, in his own words: “The Water Rat knows what every child knows, that school is life, not just preparation for it; and he knows what every great scientist knows, that much learning and most discovery occurs through serendipity… There must be time for reading what isn’t assigned, for doing an experiment you thought up for yourself, for painting something the way you imagine it instead of the way it looks. There must be time for playing ball or hanging out in the school yard… for taking bike rides to nowhere on the way home… And there certainly must be time for daydreaming. As the body develops and consciousness grows, there must increasingly be time for sorting out your place in events and circumstances and relationships and for dealing with the central adolescent question which most of never fully answer – for wondering who am I.”

My Life In School is dedicated to Sobol’s longtime associate and amanuensis, Gibran Majdalany, and to his wife, Harriet Sobol. “Without Harriet, there would be no me,” he writes, in the book’s final line.

To order copies of My Life In School, email Harriet Sobol at hsobol4336@gmail.com or visit Bank Street Book Store at 610 West 112th Street in Manhattan.

Published Monday, Mar. 4, 2013