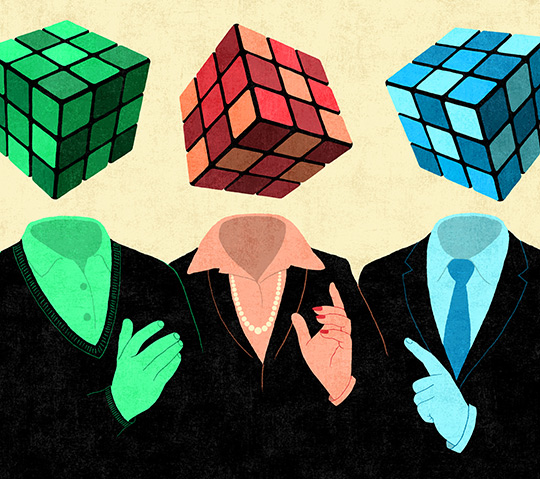

Great Minds That Don't Think Alike

TC seeks the right combination in building a faculty for the future

Teachers College has hired 50 new tenure-track professors since 2007 — roughly a third of its current faculty.

“We’re envisioning where education might be in a generation,” says TC Provost Thomas James, “so these are people we think will set the pace in their fields.”

New TC faculty members are shaping diverse approaches to new and longstanding challenges.

“Education policy used to focus on government, but with new players — nonprofits, Teach for America, charters — we have to understand markets, how nonprofits are funded, how that differs from what governments do, and how the presence of these new actors may change what government does,” says Jeffrey Henig, Chair of the Department of Education Policy & Social Analysis (EPSA).

Abroad, lenses such as ethnography are complemented by the tools of sociology, political science and economics.

“As donors and businesses target Africa and Latin America, and student performance assessments expand to developing countries, many of us are focusing on how ideas and reforms travel,” says Gita Steiner-Khamsi, Chair of the Department of International & Transcultural Studies.

Yet it is clear that the ethos behind faculty work remains emphatically unchanged.

“Beyond advancing knowledge, our people have always been uniquely committed to improving society,” says 51-year faculty member O. Roger Anderson, Chair of the Math, Science & Technology Department.

“I tell my students that leadership means ‘leadership for something,’ and that ‘something’ speaks to leadership’s ethical content,” says Anna Neumann, Chair of the Department of Organization & Leadership. “Leaders can lead toward goodness, but they also can lead for harm. Thinking through the underlying ethics of leadership matters.”

In counseling psychology, exploration of oppressed social groups’ experience “is thriving,” says Marie Miville, Chair of the Department of Counseling & Clinical Psychology. The department has launched a certificate program in Sexuality, Women & Gender and a concentration in bilingual Latina/o mental health services. A recent federal grant also supports preparation of mental health professionals to work with medical caregivers in treating HIV/AIDS, diabetes and other conditions that affect New York City’s under-served populations. TC also continues to attract funders who recognize that doing good can equate to doing well. In Asia and Latin America, there’s growing support for human rights education that empowers communities to advocate for themselves. In the United States, TC has won major funding for research and programs to support the mainstreaming of special-needs students into general education classrooms.

“TC has always been good at putting together people from different disciplines and saying, ‘Let’s figure out what we can learn from one another,’” says EPSA’s Henig.

Yet ultimately, finding answers is only half of what sets TC apart. “Disciplines are created by people, so they’re temporary ways of looking at the world,” says Hope Jensen Leichter, Elbenwood Professor of Education. “What’s important is to keep raising questions about fundamental premises — and to think beyond disciplines to identify the questions that are pertinent to a given focus of research.”

In the following pages, meet ten TC faculty members and two other innovators who are doing just that.

Learning Theorist: Nathan Holbert

Watching kids play a virtual car-racing game, Nathan Holbert quickly discovered their philosophy. “Braking is for losers,” says Holbert, Assistant Professor of Communication, Media & Learning Technologies Design. “The speed button is either on or off — it doesn’t respond to increased pressure. So kids understand acceleration as a feature of the car, not something they can alter.”

Holbert, a former high school chemistry teacher, explores how kids form perceptions of nature by playing with technology. He believes they rarely understand natural phenomena like motion through organized theories, but instead through bits of knowledge learned in different contexts.

“If you ask kids in a classroom about motion, they might recite Newton’s law, but outside school they’ll say, ‘My car was going fast, and it was really cool,’” Holbert says. “They’re excited about what they’re doing.”

Yet, children rarely apply game learnings to the real world. For that to change, Holbert believes, games should provide opportunities for personally meaningful exploration rather than “pre-defined lessons.”

To that end, Holbert has designed an experimental racing game in which kids first race using a motion-sensitive speed controller before progressing to “programming” the car’s motion by graphing the vehicle’s acceleration for each section of the track. In another game, kids explore the particulate nature of matter by designing the molecules that make up the surfaces of a game world. Through this construction process they soon intuit that an object’s hardness or softness depends not just on “what it’s made of” but also on the way the atoms are organized.

“It’s about starting where kids are at,” Holbert says. “Enabling them to do things they care about can nudge them toward more sophisticated thinking.”

Literacy for Deaf Education: Angel Wang

Born deaf in rural China, Angel Wang’s father worked in a printing house where his job was to match characters in handwritten manuscripts with those on thousands of wooden printing blocks.

“There were no deaf schools, so he didn’t know sign language,” says Wang, Associate Professor of Deaf & Hard of Hearing (DHH). “He taught himself to read and write by memorizing the characters on the blocks.”

Inspired by her father, Wang explores why, in an era of new technologies, average deaf high school students still read at a third grade level. One of the reasons: many never form mental representations of phonemes, the building blocks of languages. In a landmark 2006 study she co-authored with Beverly Trezek, “visual phonics” — hand symbols representing English language’s 44 phonemes — helped DHH kindergarteners and first graders significantly improve their reading skills. The method has since been increasingly used for children with a range of disabilities, and even for some typically developing kids.

“Middle-class kids learn phonics when their parents read to them and play word games,” says Wang. “But many special-needs or low-income kids need direct, systematic instruction.”

Wang has used that argument both to reinforce the notion that DHH students progress (albeit more slowly) through all the classic stages of language learning and to propose alternativenotions of literacy for many special-needs children.

“Literacy is the ability to access and use captured information,” Wang says. “So is a non-reading child really illiterate if she can understand a Harry Potter video with someone signing below the picture? Individuals learn in so many ways — so we have to keep an open mind.”

Desegregation’s Other Story: Ansley Erickson

"History doesn’t offer up ready-made solutions,” says Ansley Erickson, “but it does help us better understand enduring problems.”

Consider the black-white achievement gap, which Erickson, Assistant Professor of History & Education, probes in Making the Unequal Metropolis: School Desegregation and its Limits, her forthcoming book on Nashville, Tennessee. “Desegregation was an important lever for educational opportunity for African Americans, but its design also undermined black communities,” Erickson says.

As research assistant to education reformer Theodore Sizer, Erickson visited schools nationwide before teaching in Harlem and the South Bronx. Then she made a documentary about K-12 education in Nashville. Statistically the city’s school system was among the country’s most desegregated, but Erickson found that black children had been bused out of their neighborhoods three times as frequently as whites, and saw schools in their neighborhoods closed while new ones opened in the suburbs. And according to Erickson, a new emphasis on vocational education meant more black students faced “racist tracking.”

“Nashville lets you see that city planners thought of schools, housing and property values in relation to one another,” Erickson says. “So integration hasn’t failed only because white people, as individuals, didn’t want to go to school with black people. The state encouraged segregation between and within schools.” The consequences, she says, still reverberate. In the 1980s and 1990s, after witnessing busing’s toll on black children, black leaders focused less on achieving racial balance and more on securing schools for their communities. The conversation about integration’s possibilities had narrowed. “This country once saw education’s mission as broadly humanistic. But so much talk today is about preparation for work,” Erickson says. In Nashville, that focus often meant diminished opportunities for students of color. “History offers us important cautions.”

Empowering Students: Detra Price-Dennis

Most American teachers are white, middle-class and speak only English. How can they engage students who, increasingly, are of color, immigrants and from economically fragile communities? Through culturally relevant pedagogy, technology and literature, says Detra Price-Dennis, Assistant Professor of Elementary & Inclusive Education.

using digital tools to make movies and sample music, English language learners and kids labeled with learning issues can “become confident and capable producers of texts that others can interact with,” says Price-Dennis, who has studied technology use in classrooms in Austin, Texas and the Bronx. Thus teachers must become sufficiently technology-fluent to introduce digital tools and let kids run with them.

Meanwhile, literature can prompt students and teachers alike to question stereotypes, power relationships and their own thinking — in short, to care.

In an award-winning 2013 paper co-authored with Marcelle Haddix of Syracuse University, Price-Dennis chronicles the work of a former TC student, “Sam," who “complicates” the thinking of her mostly white, middle-class sixth grade students about immigration. Sam gives her students multicultural political cartoons, historical documents, poems, picture books, realistic fiction, newspaper and magazine articles and cable news reports. She asks them to contrast accounts of happy immigrants arriving at Ellis Island decades ago with the much darker narratives of many immigrants today. The students interview peers who are immigrants. They chart their own attitudes, which often evolve from viewing immigrants as invaders with language deficits to seeing them as people with different experiences and strengths.

These changes reflect what Price-Dennis calls literature’s “humanizing power” and how it serves as both a window into other people’s lives and a mirror that reflects back one’s own. Which sounds like a good description of teaching itself.

Probing Bias: Brandon Velez

In an era when identity is increasingly understood as a complex mix of biology, environment, social construct and personal choice, Brandon Velez is a researcher on the cutting edge. Velez, Assistant Professor of Psychology & Education, studies how prejudice affects people who identify as members of multiple minority groups. How is a Latina woman’s body image affected by sexual objectification and ethnic discrimination? Do racial- or ethnic-minority lesbian, gay and bisexual people experience more heterosexist stigma than white LGB people?

“There aren’t many quantitative studies assessing experiences of heterosexist stressors across racial or ethnic groups” says Velez. “However, many people believe that racial and ethnic minority communities endorse heterosexist prejudice, thus exposing LGB people of color to more heterosexism. There’s also an opposite belief that sexual minority people of color are less susceptible to heterosexism because they’ve learned to cope with racial prejudice. Until now, neither assumption has received substantial empirical attention.”

Social media has made it much easier to connect with people who identify in these multiple categories. Velez and his team use venues such as reddit and Tumblr to enroll study participants, who then self-report their experiences through online surveys.

“Online sampling has its limits, but when you lackfunds for a large-scale, population-based random sample, it’s very effective,” Velez says. “It also helps us get beyond using undergraduates, whose experiences may be less generalizable to the general population.”

Velez came to TC because “in counseling psychology, TC is one of the main hubs for multicultural research. There are fantastic people here doing great work, but just as important, there’s an openness that allows scholars to explore, regardless of whether or not their interests are ‘mainstream.’ And that keeps our scholarship cutting-edge.”

Inter-Connected: Susan Garnett Russell

The late Africanist George Bond drew from an eclectic variety of disciplines. So does Susan Garnett Russell, recently appointed Interim Director of TC’s newly named George Clement Bond Center for African Education.

Russell, Assistant Professor of International & Comparative Education, is a sociologist who applies both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to the study of education in post-conflict contexts. Her work has ranged from in-depth studies of how Rwanda and South Africa teach about their recent violent pasts to cross-national studies of textbooks that discuss the Holocaust, globalization, global citizenship, gender-based violence and nationalism, drawing on a data set of more than 500 textbooks published worldwide between 1970 and 2008. These studies find that, in general, nation-states are moving toward an inter-connected, “post-national” world culture in which participating countries are likely to teach about human rights and citizenship, regardless of their political systems. Social studies and civics are eclipsing history, a subject area often more tinged with nationalism, as the primary venue for such teaching.

Russell is building upon her earlier studies to advance research along several lines. With funding from a TC Global Investment Grant, she and her colleagues are shaping a professional development program for teachers in a United Nations refugee camp in Kakuma, Kenya. In another project, funded by a TC Diversity Grant, Russell is studying how diverse student populations in New York City public schools engage with global human rights education. In a third project, funded by a Provost Investment Grant, Russell, collaborating with TC colleagues, will lead workshops on civics education for teachers in Kenya, Malawi and South Africa. A second workshop will serve local teachers in New York City.

Somewhere, George Bond is nodding his approval.

School Readiness: Laudan Jahromi

Tapping fingers or jouncing a leg is distracting, but it may help kids with autism to “self-regulate” or improve concentration.

Laudan Jahromi, Associate Professor of Psychology & Education, builds on such insights to enhance social and emotional readiness for school among vulnerable groups of children and their parents. To that end, she’s followed children with autism in preschool and Mexican-origin teen mothers from pregnancy through their children’s entry to kindergarten.

“Inability to control outbursts or make transitions predicts bigger problems,” she says. “So how do kids learn to cope with frustration in the classroom or on the playground?”

Coping strategies often begin as joint behaviors with caregivers (think of singing a child to sleep), so “we want to focus on helping parents regulate their own frustration as we support them in scaffolding their children’s emotion regulation.”

For example, while most parents learn to sidestep battles by suggesting rather than commanding, “kids with autism respond better to commands, even when their language skills are on par,” Jahromi says. “We attribute that to perspective-taking ability. The speaker needs to be explicit when the listener can’t read between the lines.”

TC is a great place to adapt such insights for use in parenting and classroom-based intervention programs, Jahromi says.

“There’s a history here of appreciating how social context informs individuals’ development and learning, and the transdisciplinary innovation mirrors what’s happening in the autism field. We’re merging developmental and behavioral theories and strategies to maximize the benefits for kids.”

Empowering Black Girls: Monique Lane

Growing up in South Los Angeles, Monique Lane wished for a teacher who understood the trials of being black, female and serious about learning in a big, inner-city high school. She attended UCLA, where she discovered critical social theories that helped her better understand and articulate her experiences. “I decided I wanted to teach at my old high school and be the educator I’d wished for,” recalls Lane, now a Minority Postdoctoral Fellow at Teachers College.

Back at her alma mater, Crenshaw High School, Lane launched Nubia, a two-year initiative through which 28 young women (and three young men) met weekly to read black feminist literature and discuss pressing issues in their lives.

“These girls felt negatively positioned by the school’s curriculum and disrespected by many of their male peers,” she says. Each week, Lane held students accountable through a kind of tough, motherly love. “Using literature helped them challenge common stereotypes of black femininity, and most important,position themselves as agents of change. You’re offended by the portrayal of black females in hip-hop and rap culture? Well, how might you stand up against that?” Lane returned to UCLA to write a doctoral dissertation on her program’s impact on identity development and orientation to school. Soon she will publish some of her findings in a chapter in Black Feminism in Education: Black Women Speak Back, Up & Out, edited by Venus Evans-Winters and Bettina Love.

“There’s so little out there to counteract the negativity urban youth encounter in school,” Lane says. “What we did has implications for how to make teaching and learning in traditional spaces a more humanizing experience.”

Policymakers: Lighten Up!: Haeny Yoon

In a recent study, Haeny Yoon, Assistant Professor of Education, describes a typical kindergarten phonics lesson. After a half hour of sounding out words like “drum” and “crush,” a little boy named Joe propped himself onto his knees to look at the manual resting on his teacher’s lap and questioned, “Are we done with Heggerty [the publisher’s name] yet?”

Yoon, who emigrated from Korea at age two, challenges the notion of a single pathway to literacy. “My school discouraged immigrant kids from using their native languages, so no one knew about my life at home,” she says. “I was highly literate in Korean, but I was considered incompetent because of my English mechanics.”

Yoon went on to teach elementary school and earn a Ph.D. at the Universityof Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where she studied with Anne Dyson, the long-time research partner of TC Professor Emerita Celia Genishi. Like them, she believes that children develop language and literacy through creative play and that their play can be a rich source of information for teachers. At the University of Arizona, where she taught before coming to TC, Yoon studied kindergarten classrooms where children were beginning to write. While some teachers pounded home phonics and formalized writing, others embedded writing activities in play.

“The kids saw writing as a tool to enhance their play,” she says. “The more authentic and mindful writing happened around play through social relationships — including writing ‘love letters’ and birthday party invites.”

With universal pre-K in New York City prompting a stricter focus on basic skills, Yoon urges teachers to protect playtime. “Teachers must be researchers who gather information on kids beyond academic performance. That’s what play gives you.”

Integrity in Mathematics: Nick Wasserman

Imagine you’re weighing the truth of a mathematical conjecture. The conjecture, in fact, is false but appears to be true based on some initial cases. If you simply plugged in a few numbers to test the conjecture, you might quickly conclude that it is true. If you used larger numbers and discovered the conjecture didn’t hold, you still wouldn’t know why. Only through deductive reasoning — logic drawing on mathematical definitions and axioms — could you understand where the conjecture breaks down and why it is false.

In a recent study, Nick Wasserman (Ph.D. ’11, M.A. ’08), Assistant Professor of Mathematics Education, posed a few similar propositions to middle and high school math and science teachers. Many of the science teachers responded that the conjecture was true and reported feeling confident in their justification because their conclusions were empirically grounded. Some math teachers relied more on deductive reasoning, and those using more empirical evidence reported less confidence in their conclusion.

As U.S. education policy increasingly considers instruction that integrates the four math-related STEM disciplines (science, math, engineering and technology), Wasserman’s findings suggest that mathematical approaches drawing on deductive reasoning skills may be a casualty. Beyond the obvious practical consequences, Wasserman, who switched his major from architecture to math after enrolling in a STEM teacher preparation program, worries about broader questions of teacher education.

“Teachers need a sense of their discipline’s principles of inquiry — how new ideas get added and deficient ones dropped,” says Wasserman, who with TC faculty member Alexander Karp recently co-authored Mathematics in Middle and Secondary School: A Problem Solving Approach. “If STEM education is going to integrate the disciplines, teacher education must attend to the epistemological and ontological similarities and differences in each field.”

Setting The Beat In Education: Sarah Garland

In writing a book about Central American gangs on Long Island, Sarah Garland discovered that segregation and other school-related issues were part of the story. For Garland, now Executive Editor of The Hechinger Report — the award-winning news service of TC’s Hechinger Institute on Education and the Media, it’s been that way ever since.

"Journalists are curious about everything, and the education beat has it all," says Garland, a former reporter for The New York Sun and Newsday. "Politics, policy issues, social justice, people — there’s overlap with so many other issues."

As befits a media operation headquartered at Teachers College, Hechinger strives “to be more in-depth than other reporting and to look at the evidence,” Garland says. Yet in a field that has spawned a lexicon of acronyms and arcane jargon, “we also translate for the public. A Hechinger story takes you into the classroom, onto campuses or into someone’s home to show how issues like teacher evaluation or the Common Core standards translate into people’s lives.”

Under Garland’s editorship, The Hechinger Report has seen dramatic growth in traffic to its site and increasing success in placing larger stories in national and regional outlets.

“Sarah’s intelligence, sense of fairness, compassion and unfailing devotion to high-quality education journalism are a big reason for our success,” says Liz Willen, Hechinger Institute Director. Garland puts it more simply: “No one is getting tired of reading about education.” —Joe Levine

Published Tuesday, May. 12, 2015