“How does it f-e-e-e-l” to win a Nobel Prize?

By Barry A. Farber

Though Dylan disliked being designated as the "voice of his generation," his lyrics did serve to define the sensibilities of the 1960s and those of many Baby Boomers who so identified (and still do) with his understanding of myriad social issues (especially civil rights) and always-relevant interpersonal ones (especially the need for, and elusiveness of, love).

But oh those lyrics. Those remarkable, poetic, searing, unforgettable lyrics. “A great poet in the English-speaking tradition,” according to Sarah Danius, the Swedish Academy’s spokesperson. And though Dylan disliked being designated as the "voice of his generation," his lyrics did serve to define the sensibilities of the 1960s and those of many Baby Boomers who so identified (and still do) with his understanding of myriad social issues (especially civil rights) and always-relevant interpersonal ones (especially the need for, and elusiveness of, love). Arguably his most famous line, “How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?”, has been said and sung so many times that it is easy to forget the essential profundity of the words or the ways in which they represented and catalyzed momentous (if terribly overdue) societal shifts in racial perceptions. This despite the fact that Dylan himself has consistently discounted the power or genius of the song, claiming it was written in five minutes and represents nothing special.

But Dylan’s lyrics are more than just politically progressive or sociologically deft, and they’re also more than clever combinations of words or inventive rhyme schemes—as socially and artistically valuable as those characteristics are. In a book I wrote that merged my life-long interests in music and psychology, Rock ‘n Roll Wisdom: What Psychologically Astute Lyrics Teach about Life and Love (Praeger, 2007), I suggested that Dylan “was and probably remains the single best lyricist within the general rock tradition.”

Arguably his most famous line, “How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?”, has been said and sung so many times that it is easy to forget the essential profundity of the words or the ways in which they represented and catalyzed momentous (if terribly overdue) societal shifts in racial perceptions.

My hypothesis, one exemplified by Dylan (and to a great extent, too, by Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Smokey Robinson and Bob Marley), was that while many, even most, lyrics within the rock tradition are banal, there are many notable exceptions—lyrics that are smart, creative, and reflect significant psychological truths. I started the book with one of Dylan’s lyrics, “Everyone one of them words rang true and glowed like burning coal” (from Tangled up in Blue) and included dozens of phrases from his songs in the pages of the book, even “nominating” five of his lyrics as among the top 50 lyrics ever generated within the broad field of pop-rock music.

In retrospect, I’d now add two more sets of great Dylan lyrics to these. The first is from an early Dylan song later covered by The Byrds, Mr. Tambourine Man: “Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free/silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands, with all memory and fate driven deep beneath the waves/let me forget about today until tomorrow.” Extraordinary imagery of the wish for life fully embraced; compare, if you will, to the great book and movie, Zorba the Greek. The second set of lyrics that belong within the pantheon of extraordinary words written by Dylan are those from Forever Young. (Some of these words were adapted from The Old Testament’s Book of Numbers; the song itself was later adapted and revised by Rod Stewart.) “May your hands always be busy, May your feet always be swift/May you have a strong foundation, When the winds of changes shift/May your heart always be joyful, May your song always be sung/And may you stay forever young.”

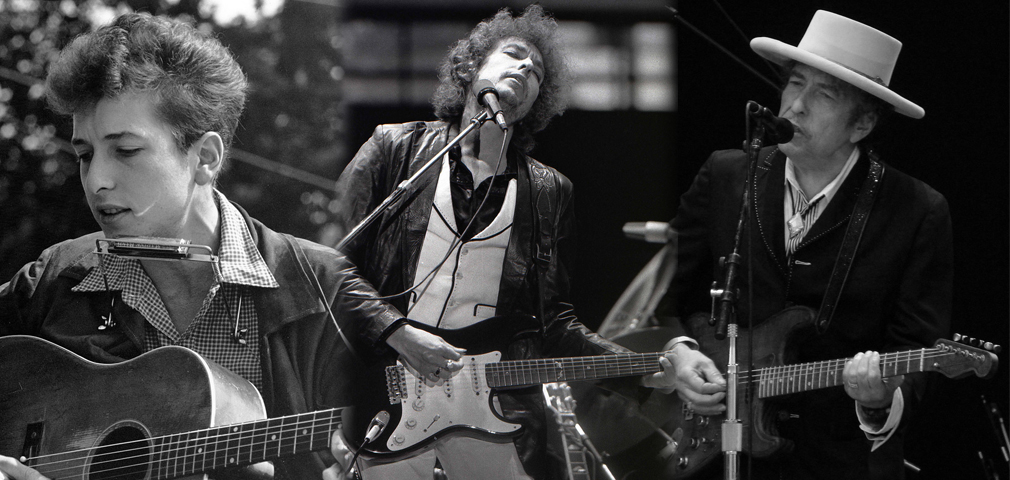

Bob Dylan is now 75, still touring, still being quoted, still in many ways forever young. And now he’s a Nobel Prize winner – one, I suspect, who still doesn’t quite know how he feels, but who is now forever displaced from the category of “a complete unknown.”

Barry A. Farber is Professor of Psychology & Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. He is the author of Rock 'n' Roll Wisdom: What Psychologically Astute Lyrics Teach about Life and Love (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007)

Published Wednesday, Oct 19, 2016