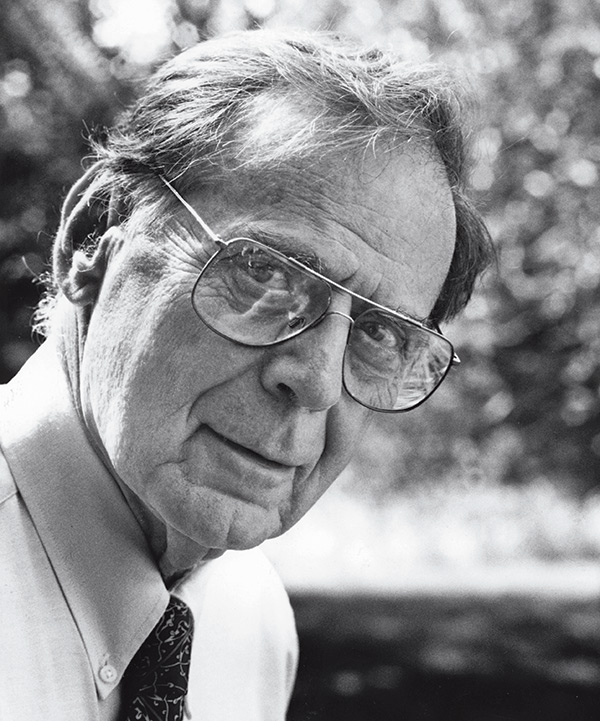

Deutsch believed that ideas validated by science could solve serious social problems (Photo: TC Archives)

(The following appears in the January 2018 issue of American Psychologist)

Morton Deutsch (1920 – 2017)

By Peter T. Coleman

Morton Deutsch believed in the power of ideas to rectify serious social problems, and in the role of science to refine our understanding of those ideas. Ranked among the 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century, he was a distinguished theorist and pioneer in the study of cooperation, conflict resolution and social justice, as well as a remarkably warm, wise and respectful mentor. He died at his home in Manhattan on March 13, 2017, at 97 years old.

Born in the Bronx New York on March 4, 1920, to Charles and Ida Deutsch, Jewish immigrants from Poland, Mort was the youngest of four brothers. A precocious student who skipped three grades in school, he entered The City College of New York at 15 where he was educated and trained to question and spar, honing his considerable intellect and skills as a scholar. As a Jew growing up in New York City and the youngest of his cohort, Mort often found himself in low power, sparking his interest in advocating for the disenfranchised. Upon graduating from City College in 1939, he went on to receive a Master’s degree in Clinical Psychology from the University of Pennsylvania. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Mort enlisted in the Air Force and became a highly decorated navigator flying more than thirty bombing missions over Nazi Germany.

“Deutsch’s theoretical work culminated in two ambitious papers: a general theoretical model of the psychosocial adaptation dynamics between people and different types of social situations, and his prophetic vision of the processes and institutions necessary for a more peaceful and prosperous world.”

Returning from WWII, stunned by the horrors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Deutsch turned his mind to addressing societies most daunting social ills. Recruited by Kurt Lewin to join the now famous Research Center for Group Dynamics at MIT as a PhD student, Deutsch took on a rigorous theoretical and empirical study of the conditions that could help the world avoid global thermonuclear war. His resulting theory of cooperation and competition became a foundational model for fostering constructive relations in all realms of human interaction. It has been applied across the globe from pre-schools to the United Nations, including being credited for promoting the nonviolent transition from communist rule to democracy in Poland in 1989.

Deutsch’s work on cooperation and conflict resolution was the beginning of a prestigious career linking theory with science to inform policy and practice. His classic 1951 study with Mary Evans Collins on interracial public housing has been credited with helping to end legally sanctioned racial segregation in the United States. In 1956, while at Bell Laboratories, he and Robert Krauss developed the renowned Acme-Bolt Trucking game, which facilitated his work on trust and threat in the context of bargaining situations. In 1962 he co-edited the book Preventing World War III, which was influential in shaping high-level U.S-Soviet dialogues on nuclear deterrence. Later in his career he turned his attention again to issues of social justice, looking to “interrupt oppression and sustain justice” by offering his 2006 Framework for Thinking about Oppression and its Change. Deutsch’s theoretical work culminated in two ambitious papers: a general theoretical model of the psychosocial adaptation dynamics between people and different types of social situations, and his prophetic vision of the processes and institutions necessary for a more peaceful and prosperous world.

Deutsch held numerous leadership positions, including faculty positions at Teachers College Columbia University and New York University and various presidencies, and accumulated dozens of awards, including eight lifetime achievement awards and the creation of four awards in his name. He also trained as a psychoanalyst and had a private practice for many years. In 1986, he founded the International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution at Columbia, where he continued to work and welcome students well into his 90s.

Mort was an avid lover of theater, chamber music, art and the restaurant scene in New York City, and spent many years entertaining friends, playing tennis and swimming in the Long Island sound at his summer home in East Hampton, New York.

But most important was the impact that Mort had on the people in his life. He was married for 70 years to the ever-remarkable artist Lydia Deutsch, was a caring father to his accomplished sons Tony and Nick, and a proud grandfather and great-grandfather. He was a mentor to over 70 PhD students, many of whom stayed in close contact with him and went on to become leaders in the fields of peace, conflict and social justice. Mort’s life, his work, his brilliance, wit and gentleness, fundamentally changed the courses of all of our lives.

Peter T. Coleman is Professor of Psychology & Education and Director of the Morton Deutsch International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution at Teachers College, Columbia University

The views expressed in the previous article are solely those of the speakers to whom they are attributed. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the faculty, administration, or staff either of Teachers College or of Columbia University.