The late advertising guru Carl Ally famously dismissed consultants as people who borrow your watch to tell you the time.

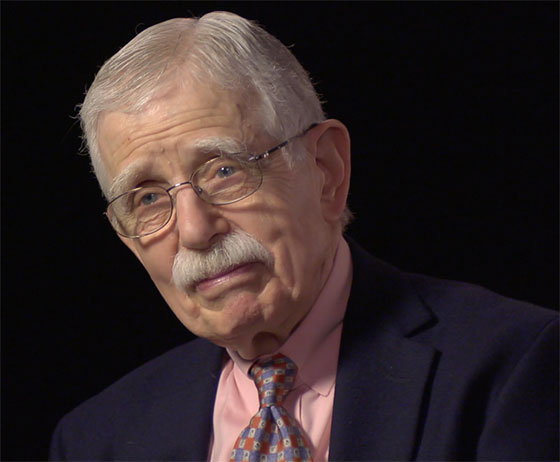

Robert Schaffer doesn’t agree, but the approach that has made him a legend in the business does indeed center on getting organizations to solve their own problems.

ALL ABOUT RESULTS Schaffer has helped organizations set and achieve goals such as saving millions of dollars or ensuring prompt customer service for an entire region.

Schaffer (Ed.D. ’52), who received Teachers College’s Distinguished Alumni Award in 2012, is the creator of Rapid Results – a system that calls for teams of employees to set their own goals, figure out how to achieve them and deliver results in 100 days. The goals aren’t process-y things like better communication or more teamwork. They’re concrete and typically formidable – like saving millions of dollars or ensuring prompt customer service for an entire region.For the past half-century, Schaffer Consulting (which Schaffer founded and where he still, though technically retired, serves as partner emeritus) and an offshoot venture, the Rapid Results Institute, have used the approach with clients that include the World Bank, AT&T, Merck, General Electric, the Veterans Administration and many more. The Harvard Business Review has written about the firm’s work and repeatedly published their papers and case studies.

[Read Schaffer’s article, Achieving Performance Breakthroughs: How a few core principles – first highlighted by Schaffer Consulting – have proved themselves over 50 years – and work even better today.]

If Schaffer’s method sounds as though it would make John Dewey proud, that’s no accident. Teachers College, where he studied organizational effectiveness with Ken Herrold and Donald Super, was a pivotal experience for him.

“The main thing that TC teaches is, you have to focus on learning, not on teaching. And I discovered early on that most consultants violated that rule with the worst of what used to be considered teaching – get an expert, pass on his expertise and then everything will be OK.”

“The main thing that TC teaches is, you have to focus on learning, not on teaching. And I discovered early on that most consultants violated that rule with the worst of what used to be considered teaching – get an expert, pass on his expertise and then everything will be OK.”

– Robert Schaffer

Schaffer was also powerfully affected by his experience, prior to founding his own firm, consulting for a petrochemical refinery called Bayway, a subsidiary of Exxon (then Esso). The parent company had dramatically downsized Bayway, and employees and even some senior managers were arguing that the cuts were too deep. Eventually, there was a wildcat strike that lasted for four months – yet during that period, Bayway kept things running, profitably and without mishap.

“It was amazing to look around and observe a few hundred managers, supervisors and engineers doing the bulk of what 2,700 people ‘couldn’t possibly do,’” Schaffer writes. “It was, you can imagine, a life-changing experience for a newly minted management consultant… We determined that we had to see what there was about that Bayway ‘magic’ that we could capture and use in our practice.”

Schaffer and his colleagues distilled four key principles from the Bayway experience.

GLOBAL IMPACT Schaffer at a meeting with staff from the World Bank.

The first is to “exploit the hidden reserve,” meaning that organizations should look in-house for the capacity to dramatically improve performance, because that capacity is almost certainly there – it’s just a matter of recognizing and empowering it.

The second is to create a sense of urgency. Neither the goals nor the deadlines can be optional – and management must not ask permission to set them.

The third is to experiment with rapid success through a pilot project in which a single group sets and achieves a measurable goal in a very short period.

And the fourth, once rapid success has been achieved, is to identify the “ingredients” that made it possible and more broadly apply them to other projects and areas of the organization.

It’s an approach that stands, in Schaffer’s words, in “stark contrast with the traditional consulting routine,” which he describes as “a long slow process to make anything significant happen: First diagnose the client’s weaknesses. Then decide on the cures for those weaknesses. Convince the decision-makers to go that way. Then create the programs that will overcome the weaknesses. Then implement those programs. Then wait for the results to occur – some day.”

Though Schaffer hatched Rapid Results 50 years ago, he believes it remains just as effective – a point he illustrates with two success stories that more or less bookend that period.

In 1967, Bell Canada pledged to provide immediate phone service to all customers in Quebec who relocated during May – a month when, owing to a tradition dating back to the Napoleonic code, one-third of the province's household moves took place. Bell delivered – even though Montreal, the province’s largest city, was simultaneously hosting Expo ’67.

In 2010, CalPERS (the California Public Employment Retirement System) set out to reduce its spending on outside investment managers. At Schaffer’s urging, one team that originally planned to merely “improve some contracts” instead “took a deep breath” and committed to saving $50 million per year. In the end, it saved nearly $100 million.

“Because the people themselves had to figure out the solutions and implement them, everyone associated with the projects developed new insights, new skills and new confidence from success, Schaffer writes. “And so it has gone for 50-plus years. The combination of the four principles are so powerful that it always works and the tangible results provide a very good (sometimes excellent) return on the investment – with the dividend being the development of new skill and confidence by everyone involved in the process.”

“You still hear about ‘change management’ as something distinct from business management, but that’s a bunch of bull. Management is change management.”

– Robert Schaffer

The Rapid Results process has been widely praised, and Schaffer’s books – High Impact Consulting (2002 Jossey Bass), Rapid Results: How 100-Day Projects Build the Capacity for Large-Scale Change (2005 Jossey Bass), The Breakthrough Strategy (1988 HarperCollins) – have become required reading in the field.

Still, Schaffer’s assessment is that “We haven’t had the impact that we were hoping for.” There’s been progress, for sure – the notion of using short-term successes as stepping stones to major advances is much more common today – but “managers hesitate to commit to achieving major improvements without the backing of tons of data and consultants prefer approaches that require more consulting effort than our approach.

“You still hear about ‘change management’ as something distinct from business management, but that’s a bunch of bull,” Schaffer says. “Management is change management.” – Joe Levine