American public education is failing black and brown children, and “not because of some person or some political party gone awry,” but because “this disparity is baked into our society,” Gloria Ladson-Billings told an overflow audience in Teachers College’s Cowin Auditorium on Monday. “It is in our laws, our policies, our rules, our ordinances, our customs and our processes. And we must be willing to admit this reality.”

Ladson-Billings, Professor Emerita and former Kellner Family Distinguished Professor in Urban Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, delivered her talk – titled “It’s ALL de jure: Turning a critical eye on the Northern Strategy” – on the opening day of the Teachers College Reimagining Education Summer Institute, now in its fourth year. In attendance was Gordon, 98, TC’s Richard March Hoe Professor Emeritus of Psychology & Education, and founder of the College’s Institute for Urban and Minority Education, whom TC President Thomas Bailey hailed as a “preeminent psychologist of this or any era.” Following Ladson-Billings’ lecture the College unveiled Gordon’s official portrait, which will hang in TC’s Gottesman Libraries.

[Read a story about the Gordon portrait unveiling.]

Ladson Billings, known for her work in the fields of culturally relevant pedagogy and critical race theory, devoted much of her talk to demonstrating that northern states have been as complicit as their southern counterparts in maintaining racial inequity, from supporting and profiting from slavery through business dealings with the South to codifying discrimination in post-World War II housing law to creating a two-tiered public education system in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court decision that struck down legalized school segregation.

“My argument is that Northern schools’ segregation was as much de jure as Southern school segregation,” she said. “Although there were no laws on the books mandating separate schools, Northern states took advantage of restrictive covenants and proliferation of community-destroying interstates to create geographic barriers between whites and blacks.”

My argument is that Northern schools’ segregation was as much de jure as Southern school segregation. Although there were no laws on the books mandating separate schools, Northern states took advantage of restrictive covenants and proliferation of community-destroying interstates to create geographic barriers between whites and blacks.

—Gloria Ladson-Billings

Ladson-Billings described personally encountering those barriers when she was a high school student at a rare integrated school in Philadelphia. An excellent student, she took advanced classes in which all her classmates were white. But in one instance, she was mistakenly put in a lower-track English class where all the students were black. The subject matter was different – grammar and spelling tests instead of reading classics and writing essays – and she easily aced all the tests. Yet she received a “C” in the course, and when she questioned the grade, she was told that it was the highest mark one could be awarded.

Ladson-Billings said that such barriers are still in place 65 years after Brown, which she called “a vision of America that doesn’t exist.” As evidence, she cited New York City Department of Education admissions tests that will result in just seven black students joining the cohort of the 895 freshmen beginning classes at the prestigious Stuyvesant High School this fall.

In a city in which 26 percent of the population is black, “the very idea that only seven black students are eligible to attend Stuyvesant reflects the way the school system is aligned against blacks,” Ladson-Billings charged.

The very idea that only seven black students are eligible to attend Stuyvesant reflects the way the school system is aligned against blacks.

—Gloria Ladson-Billings

In other cities, Ladson-Billings argued, segregation has been maintained under the banner of “school choice.” In Milwaukee’s school system, which primarily serves black students, more than a third of the public school budget is spent on vouchers, which enable students to use their share of per capita funding to attend private schools. Yet there is no evidence that voucher students are better served or achieve higher performance at the schools they attend, and meanwhile the public schools are drained of resources.

And in New Orleans, where, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, public schools were replaced almost entirely by charters, the country is seeing what happens when “a disastrous public school system meets a natural disaster,” Ladson-Billings said. More specifically, “school choice” means that “it is the schools that do the choosing,” she said, because every family now has to apply to be admitted to a school.

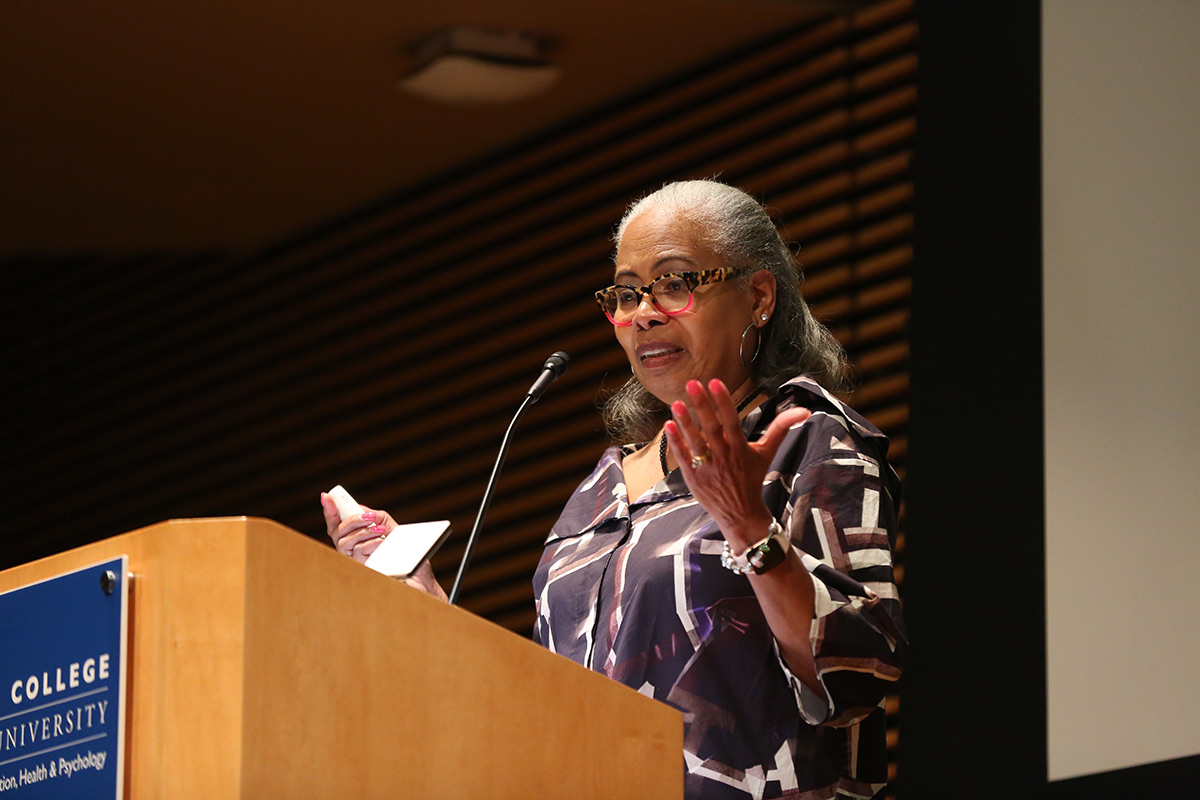

CAPACITY CROWD FOR CAPACITY BUILDING Cowin Auditorium was packed with educators from across the country and around the wolrd who were in interested in “reimagining education.” (Photo Credit: Bruce Gilbert)

“The pressure to meet state standards means charters schools can pick and choose to determine which students will enhance a school’s performance,” she said. “This attempt to enroll the more desirable students means that some students wind up on an enrollment merry-go-round shopping for a new school every year.”

Ladson-Billings said she is not optimistic about the prospects for change. It is clear, she said, that white Americans choose to live with other whites; to send their children to school with other whites; to resist and defy attempts at school integration and to fight attempts to equalize school resources. The result is that many black children ultimately end up in “the most segregated system we have – the prisons.” She reiterated her belief, expressed in previous writings, that while Brown was “the right decision,” in many ways “a real Plessy (Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court case that upheld separate but equal public schooling) would be preferable to “a false Brown.”

Still, she emphasized some positives. One was the enormous resilience of black Americans. “When you look at slavery, who else could survive this?” she said. “These are some of the most powerful people in the world. And we’re still here.”

When you look at slavery, who else could survive this? These are some of the most powerful people in the world. And we’re still here.

—Gloria Ladson-Billings

And another was the work of initiatives such as TC’s Reimagining Education Summer Institute, which each year gathers educators from around the nation to explore teaching and learning in racially diverse schools, and which represents a significant step in slowing and reversing the inequities blocking the potential of students of color.

“Hopefully,” she said, the professional development generated by the Institute and similar conferences will open channels for leaders and policy-makers to “think differently of who we are as a nation, particularly in these times.”