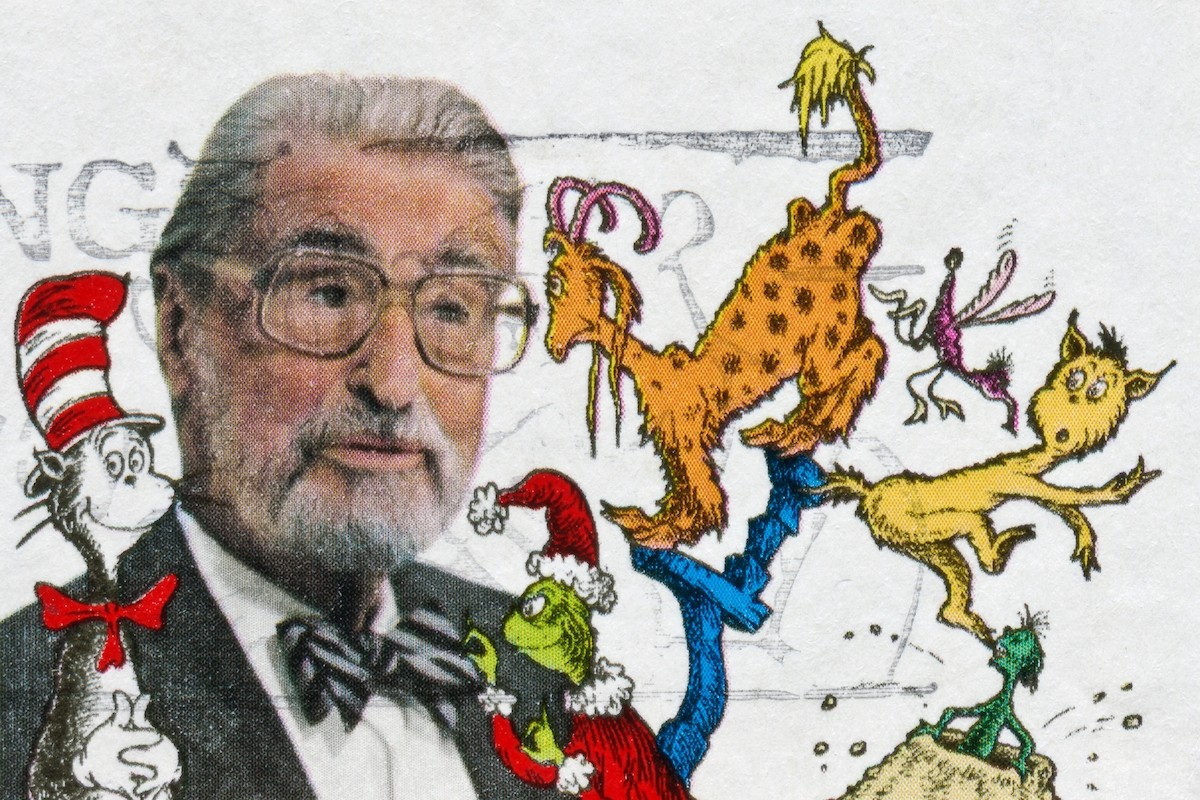

With over 600 million of his books sold during the past 80 years, the late Theodor Geisel — AKA Dr. Seuss — has revolutionized how generations of American children learned how to read. His 65 books continue to make bestseller lists 30 years after his death, and National Read Across America Day was celebrated on his birthday — Monday, March 2nd.

But young readers might never have enjoyed books such as Green Eggs and Ham and Yertle the Turtle without the scholarship of Teachers College alumnus Rudolf Flesch (Ph.D. ’43), whose 1955 bestseller, Why Johnny Can’t Read, popularized the use of phonics among educators and parents. Taking note of the growing phenomenon, publisher Random House challenged Geisel to apply Flesch’s method to a children’s book.

The result was The Cat and the Hat, a book hailed as much for its uniquely whimsical style as for its embrace of phonics. Today, the phonics method is widely accepted and applied, but in reviving and championing the idea that reading skills are built by learning how letters sound and decoding their combinations, Flesch, during the 1940s and 50s, was committing an act of rebellion.

PHONIC BOOM Flesch helped spark a revival of the phonics approach to teaching reading. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

“[Educators] believed a child could learn by osmosis. He sees a word over and over again until he learns it,” wrote the Austrian-born Flesch, who called this approach “word guessing.” But “[the theory] just isn’t so.”

As a student in what was then of TC’s library science program, Flesch tutored a sixth-grader who had been held back in school because of his struggles with reading. After realizing that the student didn’t know how to sound out words, Flesch began focusing on phonics, dramatically improving the child’s performance.

“All alphabetic languages except English are taught this way,” Flesch later told The New York Times. “Why do we do it differently?”

NOT TOO SHABBY Felsch wrote Why Johnny Can't Read and Why Johnny Still Can't Read, among other works. Photo by Morgan Gilbard.

Seuss clearly agreed, but as the children’s author grew more famous, Flesch faced continued resistance, telling The Los Angeles Times later in life that the “frustrating and unpleasant” debate among educators over his early phonics work resulted in his shift towards other kinds of language discourse.

Flesch would later return to phonics, and publishing Why Johnny Still Can’t Read in 1981, as greater efforts to measure literacy spurred additional studies and federal initiatives to confront what some saw as an emerging crisis.

Flesch passed away in 1986. While the public may not recognize his name, he holds a secure place in the field for focusing attention on phonics, paving the way for new generations of literacy scholars, improving the lives of countless children and helping to bring the world Dr. Seuss. His legacy may be best described by Seuss himself, who once said: “In these days of tension and confusion...books for children have a greater potential for good or for evil than any other form of literature on earth.”

Fortunately, thanks in part to Rudolf Flesch, many more people can read them, and draw their own conclusions.

– Morgan Gilbard