This past Tuesday morning, as thousands of mourners in Houston were assembling for the memorial service for George Floyd, the unarmed black man recently killed by Minneapolis police, more than 400 TC students, faculty, staff, alumni and friends came together for A Virtual TC Gathering: Rallying Against Police Brutality and Systemic Racism. [Watch the entire program here]

“I’ve been reflecting so much on the systemic and structural racism that is woven into the fabric of our country and thinking that this is the backdrop informing this moment of pain, confusion and outrage,” Stephanie Rowley, TC’s Provost, Dean and Vice President for Academic Affairs, told viewers in her opening remarks. The recent murders of Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and other black people have been compounded, she added, “by what we now call ‘Central Park Amy’ [the white woman who called the police on a black bird-watching enthusiast who had asked her to leash her dog, threatening to tell them that “an African American” was assaulting her] — a reminder of how liberal politics can end in white supremacy when we think no one is watching.”

I’ve been reflecting so much on the systemic and structural racism that is woven into the fabric of our country and thinking that this is the backdrop informing this moment of pain, confusion and outrage.

—Stephanie J. Rowley, Provost, Dean and VP, Academic Affairs

Yet, Rowley added, the current moment has also brought “a national and international response that I think has surprised many of us — and that renewed action on the part of our community has heartened me.” [Watch Rowley's full remarks below.]

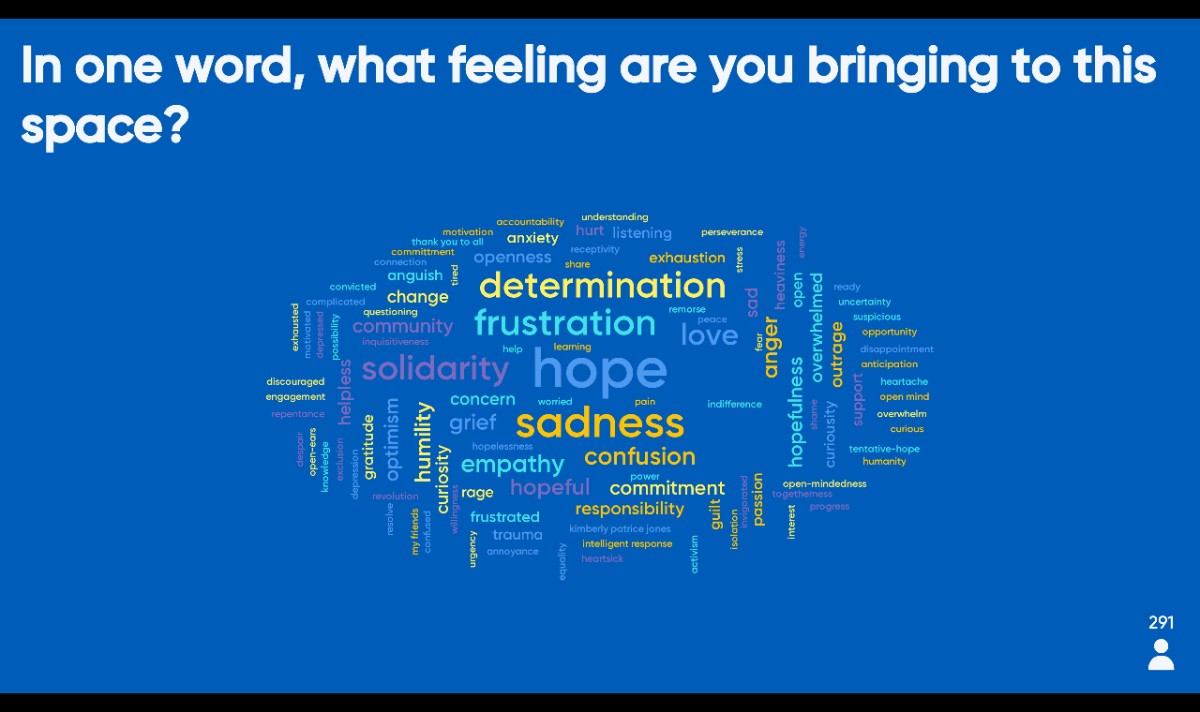

While the constraints of Zoom could not facilitate cross-talk and discussion, moderator Lily Ngaruiya, Academic Affairs Coordinator in the Provost’s Office, called on viewers to text in the words they most associate with their experience of the police murders and subsequent protests. The 200 responses included “heartache,” “peace,” “determination,” “helpless,” “accountability” and “solidarity,” but the most dominant element of the computer-generated word cloud that appeared on viewers’ screens was “hope.” [Watch Ngaruiya read an excerpt from the poem “C(h)ant: Breathe” by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, originally dedicated to Eric Garner, a black man on Staten Island who died after being choked in police custody in 2014.]

The other speakers who anchored the virtual gathering also shared their complex reactions to the recent murders and the larger context of racial injustice playing out through the COVID crisis.

Like Rowley, Associate Professor of English Education Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz said she has been struck by the global response to the killings.

“These tragedies, these murders, have taken place when the world is experiencing social isolation,” said Sealey-Ruiz, founder of TC’s Racial Literacy Roundtable Series. “There aren’t big-stadium sports to distract us, or bars and night clubs to drink and dance away the reality of what ails others. We are collectively sitting still and that has forced many to pay attention to things that ail their fellow humans. Things they would normally miss or ignore in the rapid movement of their lives.”

But she wondered aloud what the outcome would be.

A word cloud was generated based on live viewer submissions during the virtual event.

“If swift and adequate justice is not served, we will know America is not serious. In the same way, if, after all the protesters return home, people go back to their lives, living and teaching as they were before, not seeing, as they were before, we will recognize all of this as performance.”

On the broadest level, “black Americans need social justice and economic justice that is sustainable,” Sealey-Ruiz said. “And while that is our fight — though not one we asked for — I do believe it is incumbent on all of us as humans who share this earth to want for our brothers and sisters what we want for ourselves.”

Black Americans need social justice and economic justice that is sustainable. And while that is our fight — though not one we asked for — I do believe it is incumbent on all of us as humans who share this earth to want for our brothers and sisters what we want for ourselves.

—Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Associate Professor, English Education

In the meantime, she called on her colleagues to examine the racism that, she said, “is part of TC’s culture in the same way it’s part of our society’s culture. Faculty, she said “have to be willing to have honest conversations about ways they have ignored the practice of racism, about ways they have not always treated people of color with respect and kindness.”

She urged all TC community members to conduct what she called “the archeology of the self — a deep excavation of where these issues live within us and how it impacts how we live and serve” and to practice “critical love — a profound and ethical commitment to the communities we serve, rooted in care, in respect and in promoting a sense of belonging and liberation. Love that is fundamentally connected to justice” because “the two cannot be separated.” [Watch Sealey-Ruiz’s full remarks below.]

TC Public Safety Officer Dennis Chambers (Ed.D.’10; M.A.’02; M.A. ’99) described the current moment as “another tipping point in our history” and said that “the deaths of innocent black people at the hands of law enforcement and private citizens reflect a broken America where dreams can be extinguished before they can be born. And without the capacity to dream, hope dies.”

Chambers, who earned his TC doctorate in adult learning, said that “it is easy to romanticize the notion of being a change agent, but the reality is that change often occurs through discomfort or challenge” — or what the late TC adult education theorist Jack Mezirow described as “a juncture of disorientation.” Advising listeners that “you need to be the change agent” and not to “expect change from some other entity,” he suggested a focus on rethinking the nation’s “fractured public educational system” in order to foster greater understanding and knowledge.

The deaths of innocent black people at the hands of law enforcement and private citizens reflect a broken America where dreams can be extinguished before they can be born. And without the capacity to dream, hope dies.

—Dennis Chambers, Public Safety Officer II

“We all can acknowledge the power of education, but not everyone is given the same access to the same type of education,” Chambers said, adding that “uninformed and inadequate information leads to uninformed and inadequate action.”

Yet the roots of injustice go even deeper, he suggested.

“Our political, economic and social lives are all driven by the notion of being competitive and winning,” he said. “As a society, we need to reshape our competition from a win-lose economy to one in which we can all win.” [Watch Chambers’ full remarks below.]

Like Sealey-Ruiz, Associate Professor of Practice Amra Sabic-El-Rayess said she was “encouraged by the marches around the world in support of the Black Lives Matter movement” but wondered “if there will be a real change in our society.”

Drawing analogies with the period of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, which she survived as a young Muslim teenager, Sabic-El-Rayess said the answer to her question will depend not only on “the strength of the white supremacist movement that threatens black lives from the societal fringes” but also on “the everyday covert racism that lives and breeds amongst us.”

Sabic-El-Rayess says she worries about the “covert racists,” who include “our friends, our colleagues and our neighbors” and who are “the reason why the polls failed to predict the last election.

This silent, approving racism is what allowed George Floyd’s killers to steal his last breath uninterrupted. This kind of hidden racism is embedded in all domains of American life, and it’s that kind of racism that is our biggest impediment to change.

—Amra Sabic-El-Rayess, Associate Professor of Practice, Education Policy & Social Analysis

“This silent, approving racism is what allowed George Floyd’s killers to steal his last breath uninterrupted,” she said. “This kind of hidden racism is embedded in all domains of American life, and it’s that kind of racism that is our biggest impediment to change.”

Sabic-El-Rayess said she purposely refrains from using the phrase “institutional racism” to describe this kind of hatred, which she called “the kind of racism that ensures no change occurs even when thousands march in our streets.

“Institutions do not exist in a vacuum separate from our communities,” she said. “They are a reflection of who we truly are. Our police do not act in isolation, they represent our communities, policies and rules, and by calling this ‘institutional racism’ we allow the power brokers to hide behind a façade of rules and practices that have devalued black lives for 400 years.”

She closed by declaring that “we need to act now in unity with black people but need to go beyond protests and public statements, and demand their earned and rightful seat at the table at a new, equal and just America.” [Watch Sabic-El-Rayess’s full remarks below.]

Associate Professor of Education Leadership Sonya Douglass Horsford also focused on a core of attitudes that have historically resisted change.

“None of us can be free until all of us are free — or so the saying goes,” said Horsford, founding director of TC’s Black Education Research Collective (BERC). “Yet today, in the midst of the COVID pandemic and police killings, surrounded by loss, grief, suffering and death, and despite the great devastation that these major traumatic experiences are disproportionately having on black Americans in our communities, roughly 40 percent of our fellow Americans support the current administration in its policy agenda, reflecting a rejection of the belief in liberty and justice for all.”

What James Baldwin conceptualized as the ‘white gaze’ remains detached from the racial realities of growing up black in America, where innocent black children and youth are murdered at the hands of law enforcement without consequence and controversial is the declaration that ‘black lives matter.’

—Sonya Douglass Horsford, Associate Professor of Education Leadership

Horsford charged that “the field of educational research has in some ways failed us” in confronting that reality.

“Much of our work around educational equity remains a dilemma for the cause of African-descended people because it overlooks black voices, experiences and research perspectives on the purpose and values of education, which have always been linked to equality and freedom,” she said. “To its credit, education has brought some attention to the problem of inequality of schools, but the work has been conducted through the dominant white paradigm. What James Baldwin conceptualized as the ‘white gaze’ remains detached from the racial realities of growing up black in America, where innocent black children and youth are murdered at the hands of law enforcement without consequence, and controversial is the declaration that ‘black lives matter.’”

Research on race through the white gaze “lacks the capacity to create policy change for black education” because it is “incapable of seeing, knowing, much less understanding the nature of race and racism or experiencing it firsthand,” Horsford said, adding that “This methodological deficiency in education research is our inconvenient truth.”

She closed by calling for more work along the lines conducted by BERC.

“Let’s begin with those impacted by this moment. We need more research that centers the voices and perspectives of black students, parents, teachers, education and community leaders, believing that those who are closest to the issues and the problems are best equipped to tell their own stories and develop solutions.” [Watch Horsford’s full remarks below.]

Professor of Psychology & Education Marie Miville said she was heartened by the demonstrations and protests that have occurred worldwide in response to Floyd’s murder, describing them as evidence not only of solidarity with the black community, but also of psychological health.

Miville, who also serves as TC’s Ombudsperson, recalled that shortly after the Women’s March on Washington D.C. in January 2017, she described the concept of resistance “not as a negative defensive posture, but actually as a positive critical step toward wellness, empowerment, social engagement, advocacy and change.

“Then and now, the millions of people protesting in the streets and through tweets actually engaged in important psychological interventions that address social injustice,” she said. “In short, resistance is not futile. In fact, it is essential to our health and well being — even our lives.”

Nevertheless, she acknowledged that “the righteous anger and actions so bravely on display in the past few weeks highlight how pervasive these oppressive systems remain in American life.

Resistance is not futile. In fact, it is essential to our health and well being — even our lives.

—Marie Miville, Professor of Psychology & Education

“As a result of these harsh realities, I strongly believe that what is personal and political must become part of our essential work as educators, psychologists and counselors, health care workers and policymakers,” she said. As a psychologist, she said, she contends with how “systemic oppression and racism … enters our hearts and minds” and works to ensure that it never enters “our souls and our belief in our humanity.”

“By internalizing racism, you may come to believe negative connotations, lies, misrepresentations about who we are — who people of color are — or that something is your fault or your deficit that you need to deal with,” she said. “And sure, we all need to deal with our thoughts, feelings and behaviors — but it’s more about how we can figure out actions and strategies that change systems and not bring systems negative impact on us.” [Watch Miville’s full remarks below.]

The gathering closed with Janice Robinson, TC's Vice President for Diversity and Community Affairs, offering a poignant historical perspective that began during her childhood, with the death of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old African American boy who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955 after being accused of flirting with a white woman at her family's grocery store.

“I, too, am angry and tired,” Robinson said. “We keep calling the names over and over of our murdered black men and women. There is a sense of slow anti-black violence that affects each of us, that continues.”

I, too, am angry and tired. We keep calling the names over and over of our murdered black men and women. There is a sense of slow anti-black violence that affects each of us, that continues.

—Janice Robinson, Vice President for Diversity & Community Affairs

Robinson expressed the hope that “we not just keep talking,” but also that “each of us take the reasonable and swift actions which critical love dictates to do this work on anti-black racism, in our lives and in our programs.”

That work could begin, she suggested, by everyone taking, each day, a minimum of eight minutes and 46 seconds — the length of time that Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on George Floyd’s neck — “to reflect on where we are and what actions we are taking with others.” [Watch Robinson’s full remarks below.]

—Steve Giegerich

A Personal Response Creates a Public Forum

It began late last week as Stephanie Rowley, TC’s Provost, Dean and Vice President for Academic Affairs, sat looking at a Facebook feed of the names of black people — “uncles, brothers, sisters, grandfathers, grandmothers” who have died in disproportionate numbers from COVID-19. Outside her window, TC’s flag flew at half-mast, and across the nation and around the world, huge crowds were massing in protest of the recent murders of George Floyd, Breanna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery and others.

Moved by “a deeply personal experience of pain and loss,” Rowley picked up the phone and called Janice Robinson, TC’s Vice President for Diversity & Community Affairs, and within minutes the planning was underway for the community “safe-space” event that became A Virtual TC Gathering: Rallying Against Police Brutality and Systemic Racism.

Ultimately, a cross-section of people and offices across TC helped stage and conduct the event, from College Events and the Office of the Web to the principal speakers themselves. But Robinson offered special thanks to Rowley for her leadership in carrying forward the College’s tradition of supportive gatherings.

“It’s become very much a part of us, unfortunately for really difficult reasons — but it’s part of what we do,” she said. “I’m hopeful we will gather again soon. I’m sorry that we have to gather for these reasons, but to bring us here has been moving and important.”

—Steve Giegerich