In an interview in 2009, the Teachers College anthropologist Lambros Comitas observed that phones, the internet and airplanes had turned his craft into a 24/7 proposition.

“Back in the good old days of Margaret Mead and the rest of them, you’d travel for months to some remote destination, stay for a year or two, and return home, often never to go back,” he mused. But in recent years, Comitas said, the Korean grocer near his apartment had employed “two guys — one Barbadian and the other Bolivian” — from communities where the anthropologist himself had done extensive field work. “I’d go by and one would tell me in Spanish what was happening that day in Bolivia and the other would tell me in English what was happening in Barbados. The communication flow now is so open that you can constantly expand your research and continue it longitudinally.”

The story says as much about Comitas, TC’s Gardner Cowles Professor of Anthropology & Education, who died in early March at age 92, as it does about the field of anthropology.

“From my perspective, if I’m running the State Department, and I’m interested in what’s happening in Iran at the moment, I’d call in all the boys who worked there back in the 1930s, 40s and 50s and use not just their advice, but also anecdotes and whatever else to try to piece together a strategy to deal with the problem at hand.”

— Lambros Comitas

Like Mead, Comitas helped shift his field’s focus from primitive peoples to communities functioning in industrial societies. Lampooning the stereotype of the anthropologist as “some clown in a pith helmet, wondering about the bumps on people’s heads,” he helped shape an applied anthropology that consciously sought to aid other disciplines, address societal issues of the day, and — through TC’s Joint Program in Applied Anthropology, which he founded, partly in recognition of the dwindling number of academic jobs — dispatch an army of graduates to a range of different fields.

NAVIGATING NEW TERRITORY Comitas focused new attention on the Caribbean with studies of fishing communities in Barbados and Jamaica in which he introduced the concept of “occupational multiplicity” — a framework that described the complex lives of workers who plied a variety of trades in order to survive in harsh post-colonial economies. (Photo: Lambros Comitas)

“From my perspective,” he once said, “if I’m running the State Department, and I’m interested in what’s happening in Iran at the moment, I’d call in all the boys who worked there back in the 1930s, 40s and 50s and use not just their advice, but also anecdotes and whatever else to try to piece together a strategy to deal with the problem at hand.” With typical irony, he also noted that the ranks of his profession included the Haitian dictator Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier and Jomo Kenyatta, whose presidency of Kenya ended in one-party rule and the suppression of ethnic minorities. “Getting a degree in anthropology may be the best way to understand high-level political figures, but not necessarily to be those people.”

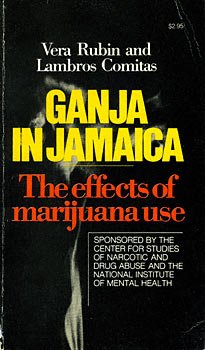

Comitas himself was recognized as one of the world’s great authorities on the Caribbean, a region that, as a former student, the anthropologist Gerald Murray, wrote in a tribute, had been “looked down upon by anthropologists as not having a ‘real culture’” because “the indigenous population had died out” and the countryside was “littered with Coca Cola signs and tourist traps.” Comitas’s own focus on societal issues included the use of marijuana, which he studied extensively. In a 1975 report, Ganja in Jamaica: A Medical Anthropological Study of Chronic Marihuana Use, which was the focus of a major article by science writer Walter Sullivan in The New York Times, Comitas and his coauthor, the anthropologist Vera Rubin, championed cannabis as a medically safe substance that should be decriminalized.

AHEAD OF HIS TIME A 1975 study by Comitas and Vera Rubin, which found that longtime marijuana users in Jamaica suffered no adverse health consequences, made headlines in The New York Times and across the United States.

More broadly, influenced by his mentor and frequent collaborator, the Jamaican anthropologist M.G. Smith, Comitas was an analyst of social organization, informal sector economics and education. Through his observation of fishing communities in Barbados and Jamaica, he developed the concept of “occupational multiplicity” — a framework that described the complex lives of workers who, to survive, also farmed, sold goods and services, and contracted themselves out as cutters of sugar cane. Occupational multiplicity was explicit refutation of more simplistic classifications by neo-liberals, Marxists, market economists and others who stayed within stricter disciplinary and ideological lines.

“The crux of Lambros Comitas’s work, and inner inspiration, was that he did not wish to present a lifeless structural analysis of Caribbean society — an anthropology of victimhood,” wrote Donald Robotham, Professor of Anthropology at the CUNY Graduate Center, in an essay presented as part of a session honoring Comitas at the 2007 meeting of the American Anthropological Association. “Lambros thought it essential to demonstrate that the individuals caught for hundreds of years in the net of British colonialism were not simply passive objects shunted hither and thither by larger structural forces which couldn’t care less about them.” Robotham — himself a graduate of the University of the West Indies in Jamaica — added that Comitas “wanted to show that Caribbean people made every effort to take hold of their own destiny and to seize whatever initiative they could eke out from the hostile world in which they found themselves. His point was to affirm the agency of people and to show that they in fact never accepted the subordinate positions which history had so far reserved for them.”

Jack of All Trades, Master of Many

Like the people he observed and wrote about, Comitas defied easy categorization. “Occupational multiplicity is an expression of his scholarship and also, I might add, of his personal pursuit,” wrote his longtime friend and Teachers College colleague, George Bond, who died in 2013.

“Lambros thought it essential to demonstrate that the individuals caught for hundreds of years in the net of British colonialism were not simply passive objects shunted hither and thither by larger structural forces which couldn’t care less about them. His point was to affirm the agency of people and to show that they in fact never accepted the subordinate positions which history had so far reserved for them.”

— Donald Robotham

A self-professed “wanderer” interested in “the differing nature of societies,” Comitas also conducted significant research in Spain, Canada, Bolivia, Costa Rica, his native Greece, Russia, and the former Soviet republics of Azerbaijan and Georgia, working in often-harsh conditions that nevertheless, as students recalled, did not prevent him from appearing for the evening meal in dinner jacket and silk cravat. He applied his theories to fields as diverse as education, the future of biology, and, in recent decades, the study of disasters such as Chernobyl, 9/11 and the California fire storms — an interest that, several colleagues and students have suggested, would likely have led him to explore Manhattan’s streets and supermarkets in recent weeks without regard for his own safety. He also was a prolific and talented photographer who, according to two former students, Renzo Taddei and Kenneth Broad, who both use film extensively in their own work, believed that “visual ethnography” was as important as written note-taking and whose style incorporated “the virtues of some of the best photographers of the 20th century: the sophisticated visual compositions that we find in Cartier Bresson, the tender view of everyday life of Doisneau and the use of counter-light that we see in Salgado’s work.”

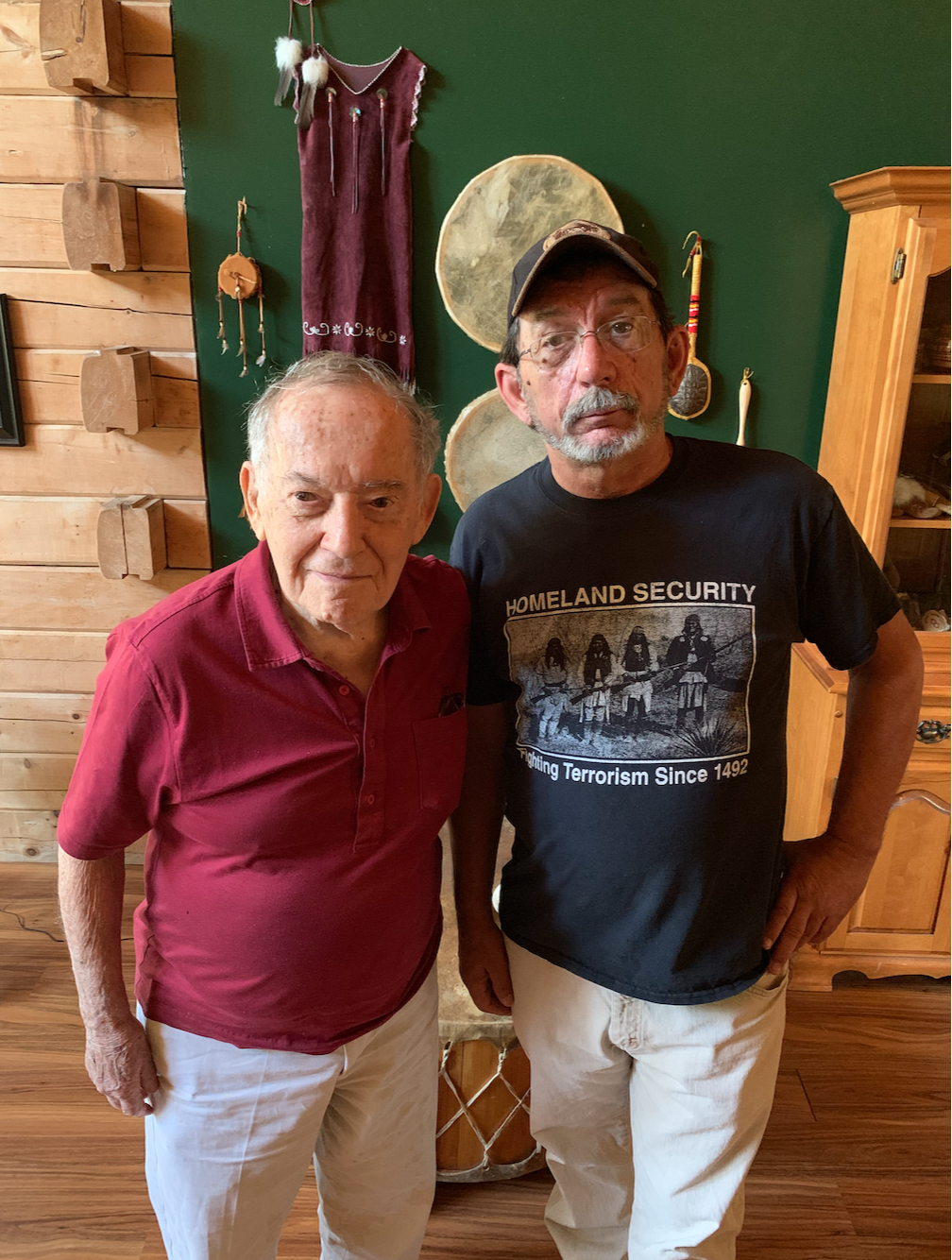

WISE GUY Comitas liked to poke fun at the world, himself included. On a recent trip to visit indigenous cannabis dealers in Canada, he fell in love with a pair of wraparound sunglasses. (Photo courtesy of James Hamilton)

A steadily widening group of other scholars has also applied Comitas’s concept of occupational multiplicity to political economy, informal economy studies, culturalist anthropology, post-structuralist anthropology and other fields. Many of them number among the more than 100 Columbia and TC students who wrote their dissertations under Comitas’s supervision. That group includes prominent academic anthropologists such as Murray, an emeritus professor at the University of Florida who is an authority on Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and more latterly, conflict in the Gaza Strip: Shirley Brice Heath, a linguistic anthropologist and professor emerita at Stanford University; Conrad Kottak, professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, an expert on Brazil and Madagascar; Bambi Schieffelin, a linguistic anthropologist at NYU; and the late Barry Chevannes, who was professor of anthropology and Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of the West Indies. But Comitas’s proteges have also included Ruth Lubic, a MacArthur Fellowship-winning nurse midwife who went on to become the leader of America’s home birthing movement; Melanie Dreher, former Dean of Rush University College of Nursing, who has studied medical uses of marijuana for pregnant women and other groups; and Broad, an ecosystem scientist at the University of Miami who is also a Coast Guard captain and filmmaker.

“I had never been to Jamaica, never used marijuana and never done anthropological fieldwork, so of course Lambros saw me as being perfectly qualified,” recalled Dreher, who was already a nurse when she entered TC’s anthropology program and subsequently assisted Comitas in the fieldwork for Ganja in Jamaica. “He understood that nurses acquire intimate and even illegal information about their patients, so he had more confidence in me than I had in myself. He took the same view of other fields, and today we’re seeing the results of his work — for example, CEOs in business hiring in-house anthropologists, not just to interpret corporate culture but also to assess the cultural value of their products and services.”

“He understood that nurses acquire intimate and even illegal information about their patients, so he had more confidence in me than I had in myself. He took the same view of other fields, and today we’re seeing the results of his work — for example, CEOs in business hiring in-house anthropologists, not just to interpret corporate culture but also to assess the cultural value of their products and services.”

— Melanie Dreher

Yet, modernist and changemaker though he was, Comitas was also very much a product of an earlier time in his field and in academia in general: a former student and colleague of Mead’s who spent a total of 76 years at Columbia and Teachers College, entering the university as an undergraduate when Nicholas Murray Butler, who had helped found TC, was nearing the end of his 40-year presidency. He took some of his first anthropology courses with the Americanist A.L. Kroeber, who had earned his doctorate (the first in anthropology ever awarded by Columbia) in 1901. He joined TC’s faculty, in 1964, at the urging of education historian and future TC president Lawrence Cremin, a believer in the synergy of disciplines who directed what was then TC’s Division of Philosophy, Social Sciences, and Education, and its Institute of Philosophy and Politics of Education. Comitas’s nostalgia for those times was unmistakable.

“When I was graduating with a Ph.D. in 1962, there were about 500 anthropology Ph.D.s in the United States, and despite the fact that I try to avoid reading as much as possible, being ultimately very lazy, you could read all the important things that were coming out in all of anthropology,” Comitas said in 2009. “Now it’s up to about 10,000 Ph.D.s — which is still minimal if you compare it with sociology or political science — and my students, who are very good students, do not even know the names of people 20 years ago, 30 years ago, 40 years ago. The explosion of publications that happened is both a very good thing and also creates a curious kind of literacy. It’s very narrow, without a general knowledge of the entire discipline, historically.”

His alleged laziness as a reader was belied by Comitas’ production, in 1977, of The Complete Caribbeana: 1900-1975, a four-volume bibliographic database topically organized to facilitate scholarly research on the non-Hispanic countries of the region. The product of more than a decade of work that was conducted largely by hand, this massive opus contains more than 17,000 complete references to authored publications such as monographs, readers, conference proceedings, doctoral dissertations, master’s theses, journal articles, reports, pamphlets, and more — including citations of works published in French, Dutch, German, Spanish, Papiamento, Russian, Swedish, Danish, and Portuguese.

“He was funny and brilliant and I learned a lot from him on how research could inform government policy for the most vulnerable.”

— Donna Shalala

As his anecdote about the Korean grocer’s suggests, Comitas was also a passionate believer in old-fashioned fieldwork who preached taking “notes, notes, and more notes.” In part, that insistence reflected his own coming of age in the era of “participatory observation” pioneered by the British school of social anthropologists such as Bronislaw Malinowski, and his adherence to M.G. Smith’s call for conceptual frameworks that were “free of unverifiable postulates.” But “being in the field” was also a natural extension of Comitas’s own protean powers of conversation and a gregarious nature that enabled him to connect with anyone and everyone, from the populations he studied in the field to the constant flow of visitors to his spacious office on the second floor of Zankel Hall, where the walls were adorned by giant ganja spliffs presented to him by fisherman in Jamaica and Barbados, adored him.

Lambros Comitas: Oral History

Interview conducted for Teachers College by The Narrative Trust

“He was so very social and the quintessential story teller,” said Dianne Marcucci-Sadnytzky, Director of Academic Administration in the Department of International & Transcultural Studies, who had worked with Comitas since 1983. “It was always, ‘come in and sit down.’ Everyone was welcome—there was never a dull moment, because his breadth was so amazing — he knew so much about so many things. And he touched many, many lives.”

“He was a wonderful colleague full of useful advice for a newly arrived suitemate,” recalled former TC faculty member Donna Shalala, who later served as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services under President Clinton and is now serving as the U.S. Representative for Florida’s 27th congressional district. “He was funny and brilliant and often had us in stitches with his stories from his research in the Caribbean. I learned a lot from him on how research could inform government policy for the most vulnerable. He was a marvelous human being beloved by his students and his colleagues

“Lambros was a powerful communicator — to watch him was to see a master at work,” said James Hamilton, an independent Canadian filmmaker who collaborated with Comitas during the past 20 years in documenting “indigenous resistance” among First Nation fisherman, loggers and dealers of medical cannabis. “His central characteristic was his sense of humor. And he always said, ‘you can find something in common with every person,’ and that was really his genius.”

FINDING COMMON GROUND Comitas with former Wolastoqiyik Chief Gerald "Cookie" Bear, who has defended indigenous participation in Canada's medical cannabis industry. Colleagues praised Comitas for his ability to connect with people from all walks of life. He was interested in indigenous medical cannabis operations in Canada in part because he saw strong parallels between entrepreneurs there and the Caribbean fishermen he'd studied earlier in his career. (Photo courtesy of James Hamilton)

Often, Hamilton added in a eulogy he delivered in March, those two qualities converged — such as during a recent trip when Comitas accompanied him to New Brunswick to interview indigenous First Nation medical cannabis dealers who, in the wake of Canada’s legalization, were resisting the government’s takeover of the business:

“Lambros established an immediate rapport with one young dealer when he asked about skin grafts on the fellow’s forearms: “Hash oil burns?” There was a pause, as the guy considered this little old man, then “Yes.” And a great interview followed. Another dealer told him: ‘This one’s a four-on-one blend. That’s 100 milligrams of THC to 400 milligrams of CBD. And I made it all with coconut oil.’ ‘Oh, that’s lovely,’ Lambros replied.”

A Nice Greek Boy from the Upper West Side

Lambros Comitas was born in 1927 in New York City, the son of Greek immigrants from the storied isle of Ithaca, a place to which he attached great personal and metaphorical significance. In 1989, he titled his inaugural lecture as Cowles Professor “Ithaca on My Mind,” in reference to the poem “Ithaka” by Constantine Kavafy, the opening lines of which are:

When you set forth for Ithaca

Pray that the journey be long,

Full of adventures, full of knowledge

“For me, an anthropologist with cross-cultural experience, the intellectual impact of this Kavafy poem is powerful and its philosophical message profound,” Comitas said in his lecture. “For an American of Greek descent, like myself, whose mother and father were born and raised in Ithaca, it also evokes memories of the past, bittersweet dissonances, emotional detritus of a family formed in cultural transition…Kavafy captures for me the illusive core of an anthropology I value and attempt to practice.”

“He was so very social and the quintessential story teller. It was always, ‘come in and sit down.’ Everyone was welcome.”

— Dianne Marcucci-Sadnytzky

Underscoring his family’s own immigrant journey, one of his stories, which he insisted was not apocryphal, was that his father swam to America — not all the way, but by literally jumping ship when the boat he was on began sinking near Manhattan.

True or not, the story illustrates Comitas’ claim that “serendipity played a great role in everything that happened to me.” He grew up on 84th Street and Broadway — “within smelling distance of Columbia,” as he put it, but unaware of that institution’s existence until a scoutmaster brought it to his attention on the eve of his graduation, at age 16, from New York City’s public schools. He entered Columbia College in 1943, was drafted in 1946, after World War II was officially over, and as the self-proclaimed “least veteranized veteran ever,” took advantage of the G.I. Bill to graduate in 1948 with a degree in Law and Politics.

“Being a nice Greek boy, I got married rather early, and it seemed to me I should go to work,” he recalled. He got a desk job with a steamship company, but, on the advice of his dentist, applied for a New York State War Veteran’s Scholarship and suggested he apply for it, dropping off an application just before the midnight deadline. He qualified, briefly attended Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service before concluding that he lacked “the pinstriped mentality” to be a diplomat, and returned to study anthropology at Columbia, where a friend from public school, Marvin Harris, was an assistant professor in the department.

There he took a methods course with Mead, became passionate about note-taking, and was eventually offered a teaching job when he happened to walk by the office of the department chair, Conrad Arensberg, just as the latter was learning that he needed a replacement for a junior colleague.

He also came into the orbit of Vera Rubin, a Russian immigrant and Columbia anthropology graduate who — with backing from her husband, the founder of Faberge Perfumes — had created an organization called the Research Institute for the Study of Man (RISM). Rubin was interested in the Caribbean and arranged to send Comitas, who had originally hoped to do fieldwork in Greece, on an all-expenses-paid, three-month summer fieldwork trip study fishing communities in Barbados.

“We weren’t the first to study that kind of place, but it was kind of a new wave that was beginning to look at modern society, complex society — and these little islands in the Caribbean were great for this because they were small enough that they lent themselves to traditional anthropological student — a single anthropologist could wander around and do a great deal of work,” said Comitas, who would later serve as assistant director of RISM for 30 years and director for 25.

Comitas wrote his dissertation on Jamaica’s fishermen and was subsequently recruited to expand on that work by the Institute of Social and Economic Research, based at the University of the West Indies in Mona, Jamaica — a group of scholars, including M.G. Smith, convened by Jamaica’s colonial government on the eve of the nation’s independence — to find ways of promoting greater cooperation within the Jamaican fishing industry. He toured more than 160 fishing beaches and eventually concluded that he was seeing something much more complex than had been immediately apparent.

“Back then the fisherman had no shoes, he had no teeth — he had a little canoe, he went out with four or five guys and dropped a fish pot down. But as you began to look at it, you saw some very interesting differences. Some guys went out late at night, some used different equipment. And it began to dawn on my colleagues and me that what they were doing on sea was related to what they were doing, or not doing, on land. And that put you in a larger scene, the economy — because you had fisherman who were working on principles of reciprocity and redistribution but also enmeshed in capitalist kinds of things, disrupting their family patterns and taking on different sets of values for a couple of months a year.”

Ganja in Jamaica

In 1969, Comitas and Rubin were asked by Eleanor Carroll, a program officer at what was then the Center for Studies of Narcotic and Drug Abuse at the National Institute of Mental Health, to study Jamaicans’ use of marijuana. Carroll, who simultaneously commissioned related studies in Costa Rica and Greece because some health officials were advocating for decriminalization of cannabis even as concern was growing the use of the substance by teenagers, sought to address what he termed “a Sargasso Sea of fragmented scientific study and partisan policy.”

But why conduct such a study in Jamaica?

“It was extremely difficult to do such studies back then and even now in the United States, because of the contamination of other substances — not only drugs, but all the other things people take,” Comitas explained. “So it would be extremely nice if you could find a population of people who didn’t pop aspirins or do heroin, led a fairly simple, traditional life, and the only thing of clinical importance was the cannabis — the marijuana.”

“He always said, ‘you can find something in common with every person,’ and that was really his genius.”

— James Hamilton

Comitas and Rubin focused their research on Jamaicans who were longtime, heavy marijuana users — people whose consumption was 10 to 25 times higher than that of high-volume American users. Jamaica marijuana was also considered to be more potent than the Mexican cannabis that was then prevalent in the United States. “The criteria were really very high — the person had to be a user for at least 10 years and had to smoke at least 10 spliffs a day,” Comitas recalled. “These were huge cigars of the stuff.” The subjects were sent to a hospital a suburb of Kingston where they underwent “every test known to mankind” and were then compared to control subjects from the same communities, who were the same age and from the same social backgrounds, but had never used marijuana. The only discernible difference found was that smokers experienced a slightly higher incidence of hypoxia, or reduced delivery of oxygen, to tissues by the bloodstream.

“The results were quite startling, at least to many people who held the stereotype view that cannabis use was harmful. There were no chronic effects discernible on this population,” Comitas recalled in 2009. “And that was subsequently confirmed in Costa Rica, with a Mestiza population, and with the Greek population, which was Caucasian. The results were benign. If you look at the damage done by cigarette smokers, our characters were much better than heavy cigarette smokers. One of the real problems in cigarette smoking is the prepared paper. The preparation. In Greece of course, they use hashish, which is putting it into a heavy oil substance. In Jamaica, you smoked the marijuana weed, the actual plant. But this is stuff that’s organically grown. And in those days, people would wrap it up in a bag and roll up the stuff in a paper bag. There were no chemical aspects to it at all. It had no nicotine. It wasn’t addictive. In fact, definitionally speaking, it wasn’t a drug.”

The researchers also refuted the popular conception of marijuana as a “gateway drug” that led users to harder stuff.

“What we discovered, essentially is that the acute reaction to the use of marijuana depends very much on where you begin to learn to use it and the group you’re using it with,” Comitas said. “In the United States, middle class kids would say “Well, it sort of calms you down, it makes you philosophical, and you talk about nice things.” And then of course it’s easy to go from that to the a-motivational syndrome, right? You’re too damned lazy, you never get up, and all the rest of it. But you go to Jamaica, you go to Greece and it’s exactly the opposite. They say, “It makes me work.” And we actually tested for this. We put these huge machines on people, caloric intake, all sorts of stuff, videotaped them to death, and we said OK, today, you smoke like you usually smoke when you’re out working. And you get these guys on 30-degree slopes in 90-degree heat, who are chopping away with hoes and they sit down, they smoke a spliff, they get up, and the productivity goes up. So these are cultural effects. It’s sort of an active placebo — you can get anything you want out of it, in many ways.”

LEADERS IN THEIR FIELDS Comitas with former Wolastoqiyik Chief Edwin Bernard in New Brunswick, Canada. Bernard has been a prominent defender of the right of indigenous peoples to continue operating in Canada's medical cannabis trade. (Photo courtesy of James Hamilton)

The findings, ultimately published in a book titled Ganja in Jamaica: The Effects of Marijuana Use, were reported on in more than 1,000 other newspapers in the United States. In Jamaica, it was discussed in Parliament and published in installments on the front page of the Daily Gleaner, the nation’s paper of record. Around the same period, a commission appointed by President Richard Nixon urged decriminalization of marijuana possession in the United States. The commission had interviewed Comitas and Rubin, and its chair, former Pennsylvania Governor Raymond Shafer, would later write the preface to a new edition of their book. However, the commission’s recommendations were ignored. In a soon-to-be published book called The Hashish Dialogues, Comitas writes that White House tapes reveal that Nixon, who had recently established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, needed to appease the right wing of his party “so he gave them the War on Drugs.”

For his own part, Comitas remained steadfast in his view that marijuana should be decriminalized.

“Listen, I’m not a marijuana user, I’m not a drug user. I come from a generation of alcohol, I don’t kid around with this kid stuff. But I’m quite serious — I don’t have a personal stake in this thing, but it would seem to me that some reasonable laying out of the facts and of coming to grips with this issue is needed. You’ve got to get rid of the illegality. Once you have the illegal thing and it crosses boundaries, then you have the situation where it becomes almost non-stoppable, because it leads to all sorts of corruption. We end up in situations where the drug dealers are literally able to control entire regions and states. In Mexico there’s a war going on between the government and the drug lords for control of the country.”

Unfinished Business

Comitas’s travels were curtailed in recent years, primarily because he was unwilling to leave his wife, Irene, who suffered from a debilitating chronic illness. Yet he was far from idle.

He created an entity called the Comitas Institute for Anthropological Study (CIFAS), which, among other activities, has hosted an annual field school for ethnographic research. The CIFAS site also houses some of Comitas’s photography and videography.

“He taught me the real meaning of a teacher’s love. By the way he showed up for people. The letters he wrote for his students, the way he believed in you when you doubted yourself. And he always, always kept his door open.”

— Shana Colburn

He saw to the publication of one book, Education and Society in the Creole Caribbean, a study of the impact of education in recently liberated post-colonial societies, that he coauthored with the late M.G. Smith, and was putting the finishing touches on another at the time of his death. That work, titled The Hashish Dialogues, includes a collection of translated conversations with members of a Greek demimonde called “hasiklides” — users who also worked as porters, carters, food vendors, butchers, pimps, and urban musicians. It will be published soon, either privately or by an academic press.

Above all, he continued to mentor former and current students.

“He had a way of asking these questions, and I wouldn’t immediately understand how relevant and helpful they were,” said Shana Colburn, a current TC doctoral student who was Comitas’s advisee. “I knew they would be at some point, but you needed to let it percolate. And then suddenly you’d be sitting there, and it would click — ‘Oh, I see why asked that.’”

But more importantly, Colburn said, was the sense that Comitas genuinely cared. “He taught me the real meaning of a teacher’s love,” she said. “By the way he showed up for people. The letters he wrote for his students, the way he believed in you when you doubted yourself. And he always, always kept his door open. To me, that said it all.”

— Joe Levine

Sources for this story include a collection of essays about Lambros Comitas by Bambi B. Schieffelin, Ellen M. Schnepel, Renzo Taddei and Kenneth Broad, Joan Vincent, Conrad P. Kottak, George C. Bond, Donald K. Robotham and Gerald F. Murray; a monograph by Gerald F. Murray titled The Comitas Phenomenon; and an oral history interview with Comitas conducted for TC by The Narrative Trust. Special thanks to James Hamilton for sharing his eulogy to Lambros Comitas and a wealth of photographs and other archival materials.