Pavel Placido has always been drawn to medical emergencies. Spurred in part by the fact that his father, a doctor in the Dominican Republic, could not transfer his license when the family moved to the United States, the younger Placido worked as an emergency medical technician when he was 16 and in a hospital’s emergency department when he was 18. He became an exercise physiologist at NYU-Langone Medical Center, but has worked in the Cardiac Rehabilitation Unit, with people who have suffered heart attacks and other medical crises.

“You go into health care because you want to be of help in any way you can, and to try to make a difference,” he says.

But even Placido, a part-time master’s degree student in TC’s Applied Exercise Physiology Program, couldn’t have imagined just how powerfully he would be asked to make good on those words.

In March, when the COVID pandemic hit New York City, NYU-Langone temporarily closed the cardiac rehab unit and asked staff to volunteer for work on the frontlines. Placido was assigned to a hospital in Brooklyn, where initially his job was to help remove bodies of deceased patients and bring them to the temporary morgue.

“I’m a healthy person — I exercise, I eat right, I’m younger — so I was never really concerned about my own safety, especially because we were using all the right PPE — double gloves, N95 masks, Tyvek suit — and following the proper doffing procedure,” he says. “But you think a lot about being respectful to the bodies. You’re reminded that this is someone’s loved one. There’s a huge gravity to that.”

You see stuff on the news, but being there in person, you realize that the patients are by themselves, in the ICU, on a ventilator.

-Pavel Placido

More recently, working in the same Brooklyn hospital, Placido was asked to join one of several teams doing daily “proning” — a newly introduced procedure that involves turning patients who are intubated (on ventilators) onto their stomachs for 16 hours out of each day.

“The research has shown that when you lie someone on their back, their lungs can fill up with fluid,” he explains. “Putting them on their stomach opens up the airway and frees lungs from blockage.”

Each afternoon, starting at about 3:30, Placido and three other physical therapists, together with an attending nurse and an anesthesiologist who fully sedated the patient and managed all the body tubes, visited different intensive care units around the hospital, moving intubated patients into the prone position. In the mornings, at about 7:30, they returned the patients to supine positions. Several other teams were simultaneously doing the same work, and often the teams would help one another.

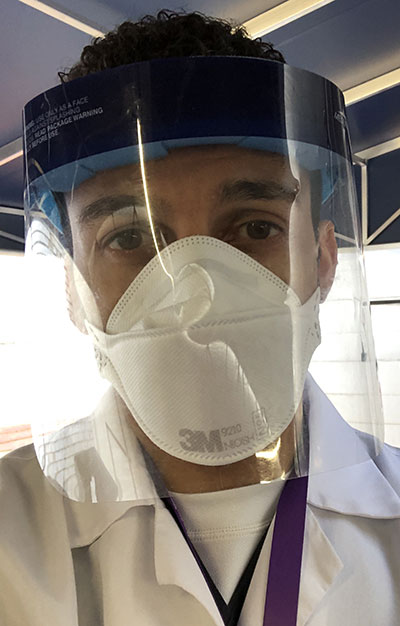

SAFE BUT SAD Placido was grateful for his protective equipment, but sad that he couldn't comfort patients. "They can't see your expression through the mask," he says. (Photo: TC Archives)

Each proning procedure took about 15 minutes, with the team changing all its protective gear in between each patient visit.

“You have to make sure all the I.V. lines and other tubes are coordinated,” Placido says. “It’s a little easier when you put people back on their backs, because the lines tend to fall naturally into place. Basically, the work is all about being as efficient as possible with your own movements — pulling, pushing, lifting. That’s why they enlist rehab specialists.”

Again, Placido says, he had to come to grips with the gravity of the work he was doing.

“You see stuff on the news, but being there in person, you realize that the patients are by themselves, in the ICU, on a ventilator,” he says. “Many of them die alone. It’s so hard. And you can’t really comfort them. They can’t see your expression through the PPE, only your eyes.”

Not all of his work was under such dire circumstances. Placido also spent several hours per day assisting physical therapists with patient care and working with non-intubated COVID patients who were recovering or in the earlier stages of the disease.

“They get physical therapy because we’re trying to assess their functions of daily living,” Placido says. “Can the patient walk safely without losing oxygen saturation? Can they be sent home, or do they need to be kept longer?”

With the numbers of new COVID cases and deaths beginning to substantially drop in New York City, Placido finished his Brooklyn deployment this past week. He’s working from home, doing telehealth sessions with recovering cardiac patients, and plans to return to NYU-Langone in about two weeks, when his clinic is expected to reopen.

But he knows that he hasn’t seen the last of COVID.

It’s really about what side of history you want to be on. That’s why I volunteered. I’d rather be helping than not.

-Pavel Placido

“Patients with cardiac issues are more susceptible to the virus — and then, there are pulmonary aspects to the work we do, too,” he says. “So, in my normal job, I’m going to be seeing a lot of recovering COVID patients coming in for rehab.”

That’s where his studies at TC will likely prove especially useful.

“One of the really great things about TC’s program is that it’s given me a deeper understanding of exercise physiology and how to apply it,” he says. “So, for example, with cardiopulmonary exercise testing — I wasn’t really that familiar previously with a lot of the unit measurements that are generated by our evaluation tools. But at TC I’ve learned in-depth what the values that patients are producing mean. And we’re likely to see some very severe pulmonary numbers when we do exercise testing on recovering COVID patients, because the virus is a restrictive lung disease by nature.”

For now, Placido’s family is heaving a big sigh of relief that he’s no longer on the frontlines.

“They were really freaked out at first, though very supportive — my mom and my aunt were texting me every day with their prayers, and now that I’m done, they’re telling me I’m a hero,” he says, smiling. It’s clear that he doesn’t look at it in quite that way. “It’s really about what side of history you want to be on. That’s why I volunteered. I’d rather be helping than not.

— Joe Levine