Three policy briefs issued this month by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) are co-authored by Teachers College faculty or recent alumni.

The briefs are part of an ongoing series by NCTE’s James R. Squire Office of Policy Research in English Language Arts that explore key issues that affect literacy educators and their students and offer student-centered policy recommendations.

In “Racial Literacy,” Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Associate Professor of English Education, addresses what others have termed a “pedagogy of discomfort” — the uneasiness and avoidance displayed by many White preservice teachers in urban schools when teaching students of color — particularly male students of color.

A desired outcome of racial literacy in an outwardly racist society like America is for members of the dominant racial category to adopt an antiracist stance and for persons of color to resist a victim stance.

— Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz, Associate Professor of English Education, in her NCTE policy brief

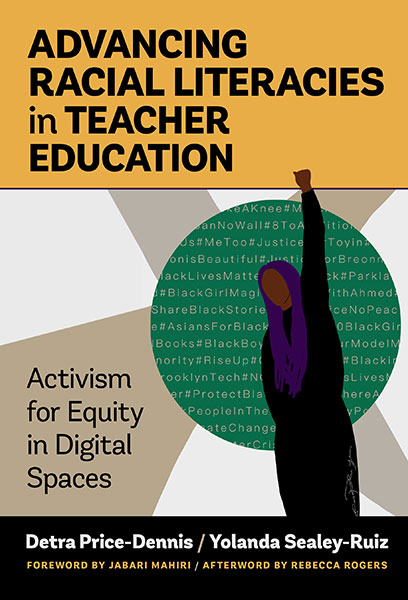

“Often this discomfort is expressed in the form of ‘color blindness’ as preservice teachers deny the salience of race by adopting a color-blind approach and view the experiences of students of color as if they were white ethnic immigrants who would eventually assimilate into mainstream society,” writes Sealey-Ruiz, who is co-author with TC’s Detra Price-Dennis, Associate Professor of Education, of Advancing Racial Literacies in Teacher Education: Activism for Equity in Digital Spaces, due out in early May from Teachers College Press.

TIMELY CONVERGENCE TC’s Detra Price-Dennis and Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz provide “theoretical and practical entry points into a conversation about race in the digital age.” (Photo courtesy of Teachers College Press)

The antidote, argues Sealey-Ruiz, is “racial literacy” — a concept originated in 2004 by Harvard University professor Lani Guinier — which Sealey-Ruiz describes as “a skill and practice by which individuals can probe the existence of racism and examine the effects of race and institutionalized systems on their experiences and representation in U.S. society.” Sealey-Ruiz argues that preservice teacher education programs are “critical sites for foregrounding the discussion of race and problematizing the ways in which the social and academic behaviors of Black and Brown students are misread.” She calls on schools of education to inculcate racial literacy as a core skill through six key practices: critical love, critical humility, critical reflection, historical literacy, archaeology of self, and interruption.

What would success look like? Sealey-Ruiz concludes:

“A desired outcome of racial literacy in an outwardly racist society like America is for members of the dominant racial category to adopt an antiracist stance and for persons of color to resist a victim stance.”

[Read a story in TC’s 2020 Annual Report about the recent racial literacy work of Sealey-Ruiz and Price-Dennis in local schools.]

ELA teachers must “critically engage media and popular culture to avoid continued harm” to students of color who continue to be “faced with a static literary canon within ELA classrooms that continues to prioritize white, Eurocentric texts.”

— from an NCTE policy brief co-authored by TC alumna Jamila Lyiscott (Ph.D. ’15)

In “Critical Media Literacy and Popular Culture in ELA Classrooms,” Jamila Lyiscott (Ph.D. ’15), Assistant Professor of Social Justice Education at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and co-authors Nicole Mirra of Rutgers and Antero Garcia of Stanford University offer strategies to help ELA teachers “critically engage media and popular culture to avoid continued harm” to students of color who continue to be “faced with a static literary canon within ELA classrooms that continues to prioritize white, Eurocentric texts.” With her co-authors, Lyiscott, who is also Senior Research Fellow at TC’s Institute for Urban and Minority Education and author of Black Appetite, White Food: Issues of Race, Voice and Justice Within and Beyond the Classroom (Routledge 2019), calls on educators to “center students as critically engaged members of a new digital social reality.”

[Read a story about (and watch a video of) a talk Lyiscott gave in Summer 2020 at Teachers College’s Reimagining Education Summer Institute.]

Schools must ascertain what language practices actually exist within the school community and then “commit to cultivating a multilingual ecology” in which the full range of those practices are “visible and palpable.”

— from an NCTE policy brief co-authored by Cati V. de los Rios (Ph.D. ’17)

And in “Understanding Translanguaging in U.S. Literacy Classrooms,” Cati V. de los Rios (Ph.D. ’17), Assistant Professor of Literacy, Reading, and Bi/Multilingual Education at the University of California-Berkeley Graduate School of Education, and co-author Kate Seltzer of Rowan University call for schools and teachers to “recognize bi-/multilingualism as the norm and leverage it for language and literacy learning.” They argue that schools must ascertain what language practices actually exist within the school community and then “commit to cultivating a multilingual ecology” in which the full range of those practices are “visible and palpable.”