When Mark Anthony Gooden conducts workshops with principals and superintendents on how to create equity-focused climates in schools, one exercise he assigns is frequently greeted with a distinct lack of enthusiasm, if not outright anxiety: the writing of a personal “racial autobiography” — an unvarnished reflection on one’s own status in the American racial hierarchy and the views one might hold as a result.

“White school leaders will often say, ‘This has nothing to do with the real work of school leadership,’” says Gooden, Teachers College’s Christian Johnson Endeavor Professor in Education Leadership and Director of TC’s Endeavor Antiracist & Restorative Leadership Initiative.

“At the end of the reflections, I ask, ‘Does anyone in this room seriously believe that race and culture do not impact the job you do as a leader?’ There’s usually a reflective pause. And then most of the time, the majority of them say it does — it’s just that they’re not sure how, or what to do about it.”

In the opening chapter of their newly released book, Five Practices for Equity-Focused School Leadership (Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2021), Gooden and co-authors Sharon I. Radd, Gretchen Givens Generett, and George Theoharis offer a vignette of just such a principal: “Ezra,” the thirtysomething head of a diverse middle school in the fictional town of Rolling Hills. Ezra is under pressure to improve his students’ performance on standardized tests. He’s also dealing with tensions that reflect events in the community, including a spate of anti-immigrant graffiti at the local mall and controversy over funding better library resources for recent immigrants.

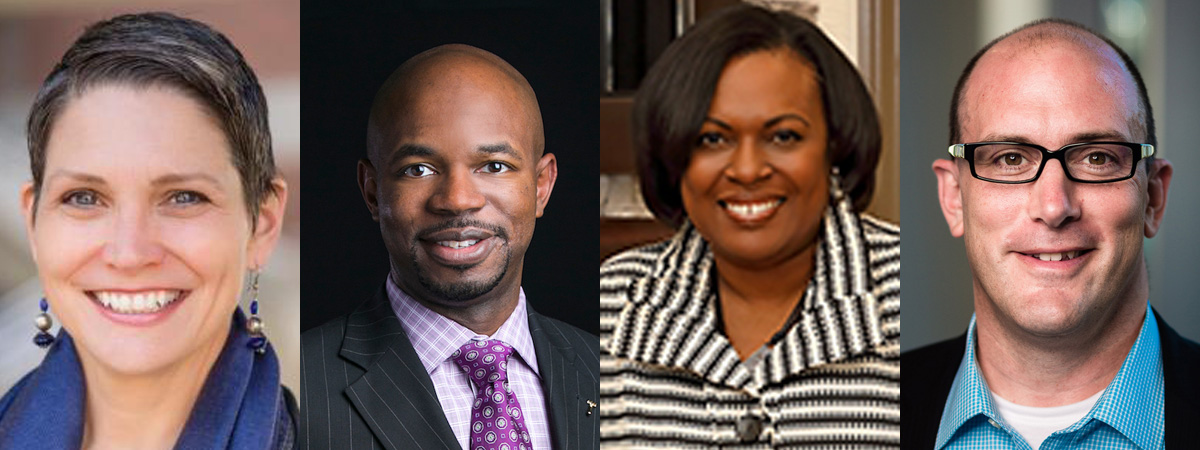

EQUITY TEAM TC's Mark Gooden (second from left) and coauthors (from left) Sharon Radd, Associate Professor of Organizational Leadership at St. Catherine University; Gretchen Givens Generett, Interim Dean and Professor of Foundations in the School of Education at Duquesne University; and George Theoharis, Professor of Educational Leadership & Inclusive Education at Syracuse University.

Ezra sees the relationships among these converging issues, but he has little time and is tempted to reach for the newest curriculum or other quick fix. Instead, Gooden and his co-authors offer a pyramid of factors he should consider. At the top are individual and interpersonal issues. At the next level down are issues playing out within the school. Next come broader structural issues in the education system and community. And at bottom are historical issues “rooted in centuries of human experience.”

Gooden and his colleagues offer school leaders like Ezra an array of “disruptive practices” that include conducting schoolwide equity audits, building equity leadership teams and introducing curricula that are of relevance to all students. But to effectively apply the pyramid, the book argues, principals must start with the individual. That’s where the racial autobiography comes in — and Gooden knows that undertaking it is often the hardest task of all.

People are afraid of being embarrassed for not understanding privilege, of feeling guilty about being a White person in America. We say right out that there are going to be steps that require you to be emotionally engaged. It’s going to be uncomfortable writing, but if you can stay with it, the results are well worth it.

—Mark Anthony Gooden, Christian Johnson Endeavor Professor in Education Leadership

“People are afraid of being embarrassed for not understanding privilege, of feeling guilty about being a White person in America,” he says. “We say right out that there are going to be steps that require you to be emotionally engaged. It’s going to be uncomfortable writing, but if you can stay with it, the results are well worth it. Because while leaders are often cognizant of inequities, they may not have recognized their own implicit biases and how those biases factor into a school’s climate, access to the curriculum, or discipline. They might come to realize, for example, that when it comes to school holidays, they may have strong leanings toward particular traditions and religious occasions. They might come to realize, too, that no one has sought student voice to see how students feel about it. Ultimately, there might be this new awareness of, ‘Hey, I’m a good person, but I’m not as good at seeing or eradicating inequities as I thought. How do I do it?’”

Watch a brief video about Mark Gooden's life and work.

In other instances, Gooden says, leaders have already done the internal, personal work but may not be taking the right approach to mobilizing others.

“Principals go through our programs and come out pumped to make positive changes, but then they get back to their schools and run into resistance,” he says. “And that’s where building your equity leadership team comes in — a team of like-minded people working with you. Because this is too hard to do alone.”

Ultimately, he says, the work of creating an antiracist environment is about implementing personal lessons learned.

How do you approach that teacher who is suspending Black and Latinx boys? How do you respond when she comes to you in tears and says, ‘Are you calling me a racist?’

—Mark Anthony Gooden, Christian Johnson Endeavor Professor in Education Leadership

“How do you approach that teacher who is suspending Black and Latinx boys?” he says. “How do you respond when she comes to you in tears and says, “Are you calling me a racist?”

Black leaders will likely face their own challenges, both external and internal.

“One principal we know identified as a Black woman and her assistant principal as a Jewish man,” Gooden relates. “In her racial autobiography, she shared how their predominantly White staff frequently looked to her AP for approval when she, as the principal, was saying what needed to be done. At a certain point, she allowed that to happen, in order to get things done. And I said, ‘You can do that, but ultimately you’re giving them a pass and endorsing the troubling belief that a Black woman can’t lead without a White man signing off.’ Her assistant principal, who was a true ally to her, felt the same way. So, we become afraid to address the folks who are doing the bad behavior, and we try to work around them. But in the end, that comes back to bite us.”

Gooden, whose resume includes more than two decades of research and culturally-relevant academic leadership at the confluence of race and law, knows that, just as in his workshops, many readers will feel defensive or even resentful when race issues are “revealed.” He doesn’t take it personally, he says, because many leaders reflexively resist interrogating race.

“Our aim is not to find how many teachers and leaders we can label as racist,” he says. “The goal is to build a community of trust and racial awareness so that we can work together to ultimately reimagine and build an equitable system. And I do think change is possible. People are going to make missteps, but if we know they are committed and courageous, we can come together to do incredible work.

No one has ever told me that the United States in the future is going to be more homogenous. We have to be prepared to work with folks different from us by working on ourselves.

—Mark Anthony Gooden, Christian Johnson Endeavor Professor in Education Leadership

“What we argue in the book is that this really is good leadership, this is good teaching, this is how we change our systems to be prepared for the future,” he adds. “No one has ever told me that the United States in the future is going to be more homogenous. We have to be prepared to work with folks different from us by working on ourselves.”