The patient is Warren Flagg, a 47-year-old high school graduate who works at the automobile plant in the town where he grew up. Flagg’s hand was lacerated in an assembly line injury and needs surgery — but his benefits were recently reduced, there are rumors of a plant shutdown and he’s afraid he can’t afford the procedure. Also, his brother died from a bad reaction to anesthesia a few years back, and Flagg has an elderly mom and two teen-aged daughters who depend on him.

Warren Flagg isn’t real. He’s a fictional character, played by an actor in a four-minute video and then represented by a manikin in an online teaching simulation. Both the video and the “sim” were created by Michele Roberts, a clinical learning facilitator at Rutgers University School of Nursing who, like many of her peers nationwide, has been using “virtual simulation” — trainings done entirely online — since the COVID pandemic began. Roberts, who also is a student in Teachers College’s online doctoral program in nursing education, is conducting a study for her dissertation to see if learning virtually about a patient’s personal history will lead her students to behave more empathetically in practice situations.

GETTING TO KNOW “THE PATIENT” An actor playing fictional patient Warren Flagg shares his character's personal story.

“We know there are better outcomes when nurses understand their patients’ perspectives,” she says. “It promotes patient buy-in and adherence to the care plan. But we move nursing students through simulation so fast — ‘this is Tom Smith, age 57, with pneumonia’ — that they end up viewing the hypothetical patient as just a manikin. So how can you promote caring toward a manikin? Will thinking beyond his condition to understand his cultural affect, his preferences, his social constraints, result in better, more empathetic care?”

Longstanding Practice

Nursing schools have used simulation since at least the early 20th century, when a Rhode Island doll company began marketing “Mrs. Chase” and “Baby Chase,” manikins with “stitched knees, hips, elbows, and shoulders.” [Read an article, “A Brief History of Simulation in Nursing,” on the website of the Connell School of Nursing at Boston College.]

Students have also continued to learn to carry out procedures on real patients during clinical rounds in hospitals, but nearly all major programs now also use sim labs — mock hospital rooms with fake patients that, according to the website Straight A Nursing, “have veins you can insert an IV into, urethras that can be catheterized, lungs that can be intubated and stomachs that can be decompressed with an NG tube” — valuable skills that nurses need that can be practiced without fear of harming patients.

As of 2019, 65 percent of all nursing education programs were also using some form of online simulation. But then the pandemic hit last March, driving nursing education largely online, and overnight, virtual simulation became, arguably, the field’s most important tool and the focus of most of the available research funding. Schools have been scrambling to adjust, and many in the field are asking: Just how good a tool is simulation of any kind when students spend less time on clinical rounds? [Read a story about a study on this topic that is being conducted at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center by TC nursing education doctoral student Wayne Quashie.] How effective are nurses who have been trained via virtual simulation, and what kinds of improvements does virtual sim teaching need to make? And how will this year’s nursing school graduates perform when they begin caring for live, flesh-and-blood patients?

A year ago, no one had heard of COVID, but now there’s a whole class of nurses who graduated last spring who had to finish their training primarily online, and this year’s cohort has been online from the start. That’s presented a huge challenge to the faculty who train them.

—Kathleen O'Connell, Isabel Maitland Stewart Professor of Nursing Education

“A year ago, no one had heard of COVID, but now there’s a whole class of nurses who graduated last spring who had to finish their training primarily online, and this year’s cohort has been online from the start,” says Kathleen O’Connell, Isabel Maitland Stewart Professor of Nursing Education at Teachers College. “That’s presented a huge challenge to the faculty who train them.”

Teachers College’s online doctoral program in nursing education, founded by O’Connell in 2016, enrolls nurse educators who teach nursing students. It has stressed teaching through simulation since its inception — and during 2020, the program and its students have moved to the fore in addressing those issues.

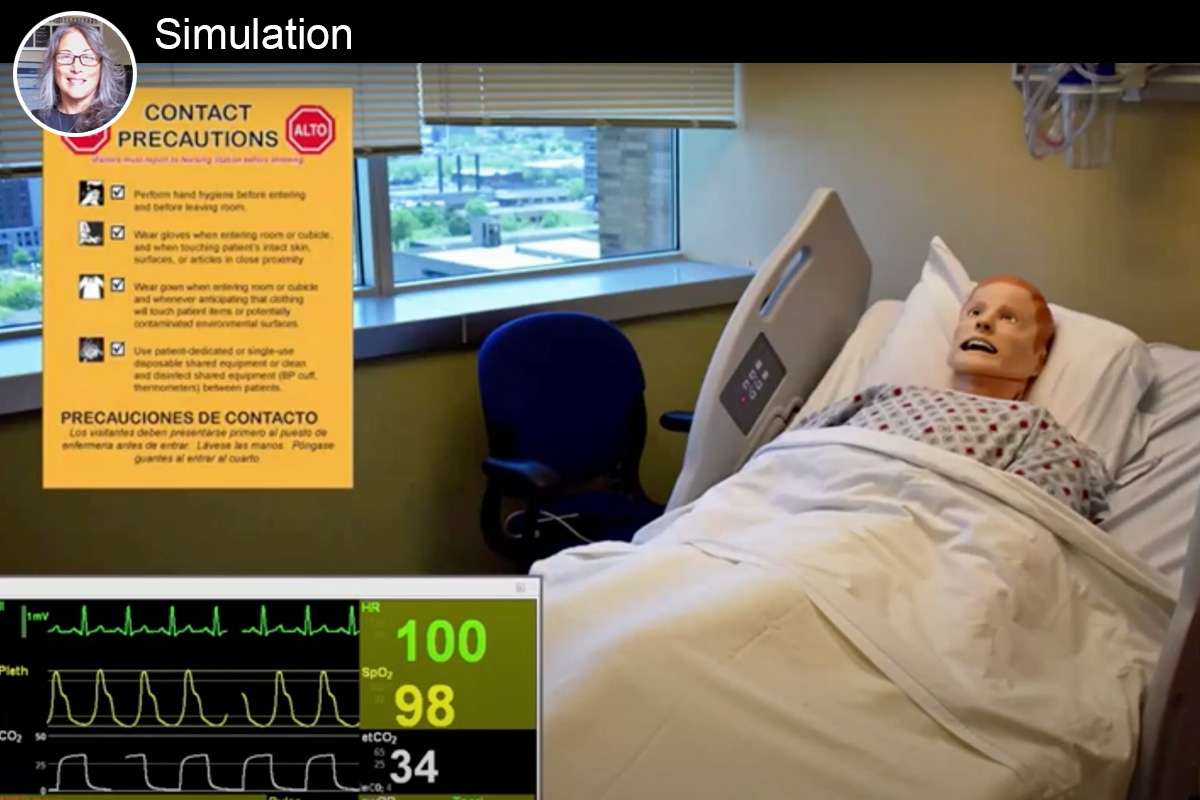

Watch a clip from a remote simulation exercise in which nursing students at Rutgers University work with a manikin who represents a newly admitted hospital patient.

“We’re an online program, which is a format that has catered to the needs of so many working nurses, so our curriculum hasn’t changed,” says Tresa Kaur, Lecturer, who teaches courses in simulation and innovations, including segments that deal heavily with online learning and virtual simulation. “But what also makes us unique is that we’re an Ed.D. program focused on research and education — our students are practitioners who are looking to improve patient care and academia through better education. Many of our students are frontline nurse educators and frontline clinicians who are taking care of COVID patients, teaching skills to their own nursing students and trying to complete their dissertations. They’ve had to make huge, rapid adjustments. It’s been very challenging for them, but the result is that now our students are really transforming virtual learning.”

Many of our students are frontline nurse educators and frontline clinicians who are taking care of COVID patients, teaching skills to their own nursing students and trying to complete their dissertations. They’ve had to make huge, rapid adjustments. It’s been very challenging for them, but the result is that now our students are really transforming virtual learning.

—Tresa Kaur, Lecturer in TC's online doctoral nursing education program

Thinking on Their Feet

A major component of their efforts centers around the use of “standardized patients,” or actors, like the one who plays Warren Flagg – an innovation that can actually provide students with more interactions with “patients.”

For example, in her day job as Nursing Simulation Educator at Columbia University School of Nursing, Nancy Spear Owen, another doctoral student in TC’s program, has created what sounds almost like a television mini-series for nursing students interested in mental health.

“Under normal conditions, our students used to go once per semester to observe a counseling session,” Owen says. “Now the Director of the Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Program and I have created an entire semester of family counseling — 45 minutes each week with an unfolding scenario at each session. It’s detailed, organic and very natural. And the students really have to interact with standardized patients and think on their feet.”

IN THE VANGUARD TC’s online doctoral nursing education program is a leader in shaping online simulation teaching. From left: Program founder Kathleen O'Connell; Lecturer Tresa Kaur; doctoral students (and nurse educators) Michele Roberts and Nancy Spear Owen.

Online sim works best with “cognitive, analytical kinds of activities” as opposed to “learning psycho-motor skills,” Owen says. “To learn to give injections, you still have to come to the sim lab and work with the equipment,” and that’s still happening, under very tightly controlled conditions.

But for experience in making quick decisions under tense conditions, she says, being online can be just as good. “We’ve flipped many manikin situations, so that the educator is in the lab, running the manikin, and students are viewing from home.”

By design, anything can go wrong with the patient in these sessions — and frequently does. In Roberts’ training session, Warren Flagg responds to an antibiotic by breaking out in a rash and becoming short of breath. A “code” team comes to his room, and for a few minutes, things feel very authentically touch-and-go.

Beyond helping nursing students in their own institutions, the work by nurse educators in the TC program is percolating outward.

In a separate effort, Owen is part of the SIPPS Trial research team that, as a public service, has created an online tool kit to guide students and new nurses through the basics of using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and other measures to prevent infection.

Learn about Teachers College’s Patricia Zirkel Lund Scholarship for Nurse Educators. Lund, who earned her Ed.D. in Nursing Education from TC in 1988), served on the faculty of Mount Saint Mary College, the Columbia University School of Nursing, the Hunter-Bellevue School of Nursing-CUNY, Western Connecticut State University, and Virginia Commonwealth University. Her specialty area was Parent-Child Nursing.

“Think of all these brand-new nursing students who’ve not been in a hospital before, and we need to get them to understand that, hey, what we taught you in the textbooks isn’t what’s happening out there in the workforce right now,” she says. “Hospitals are re-using PPE instead of disposing of it, because there isn’t enough of a supply.”

Michele Roberts and Julia Mazurak, also a student in TC’s program, have written a paper about virtual simulation, titled “Virtual Clinical Experiences: Applying a Technology-Enhanced Storyboard Technique to Facilitate Contextual Learning in Remote Environments,” which has been accepted for publication by the journal Nursing Education Perspectives. In it, they report that nursing students seemed as engaged in the virtual sim as they were during their experiences in the sim lab and stated that they felt the virtual sim was a valuable learning experience.

Part of History

Roberts also recently gave a webinar on the same topic for Laerdal Medical, a manufacturer of training, educational and therapy products that had given her a home computer license that enabled her to run her virtual sim.

I believe virtual sim will become much more widely accepted, and that it represents the future, even after the pandemic is behind us. Because without simulation we’re not giving students the ability to practice skills in a safe manner.

—Michele Roberts, clinical learning facilitator at Rutgers University School of Nursing and TC nursing education doctoral student

“You know, I never thought I’d develop an interest in technology — particularly to help improve empathy,” she says. “In fact, when I was an emergency room nurse, I noticed that the increased use of technology, along with other factors such as decreases in patients’ length of stay, seemed to contribute to a lack of empathy exhibited by nurses. But I believe virtual sim will become much more widely accepted, and that it represents the future, even after the pandemic is behind us. Because without simulation we’re not giving students the ability to practice skills in a safe manner. That’s why I chose TC’s program — because it’s really focused on improving education in ways that matter for the patient.”

And for the nurses who will take care of those patients.

I believe that the education we’re giving them right now is not less, it’s just different. We won’t know how it all plays out until they get out there, but they’re part of history, part of our response to the pandemic through their schooling.

—Nancy Spear Owen, Nursing Simulation Educator at Columbia University School of Nursing and TC nursing education doctoral student

“The students we have now are going through their entire prelicensure schooling during this pandemic — and they’re amazing,” Nancy Owen says. “I give them so much credit. They just want to learn and contribute.

“I believe that the education we’re giving them right now is not less, it’s just different. We won’t know how it all plays out until they get out there, but they’re part of history, part of our response to the pandemic through their schooling. And by rethinking how to teach them during this time, so are we.”