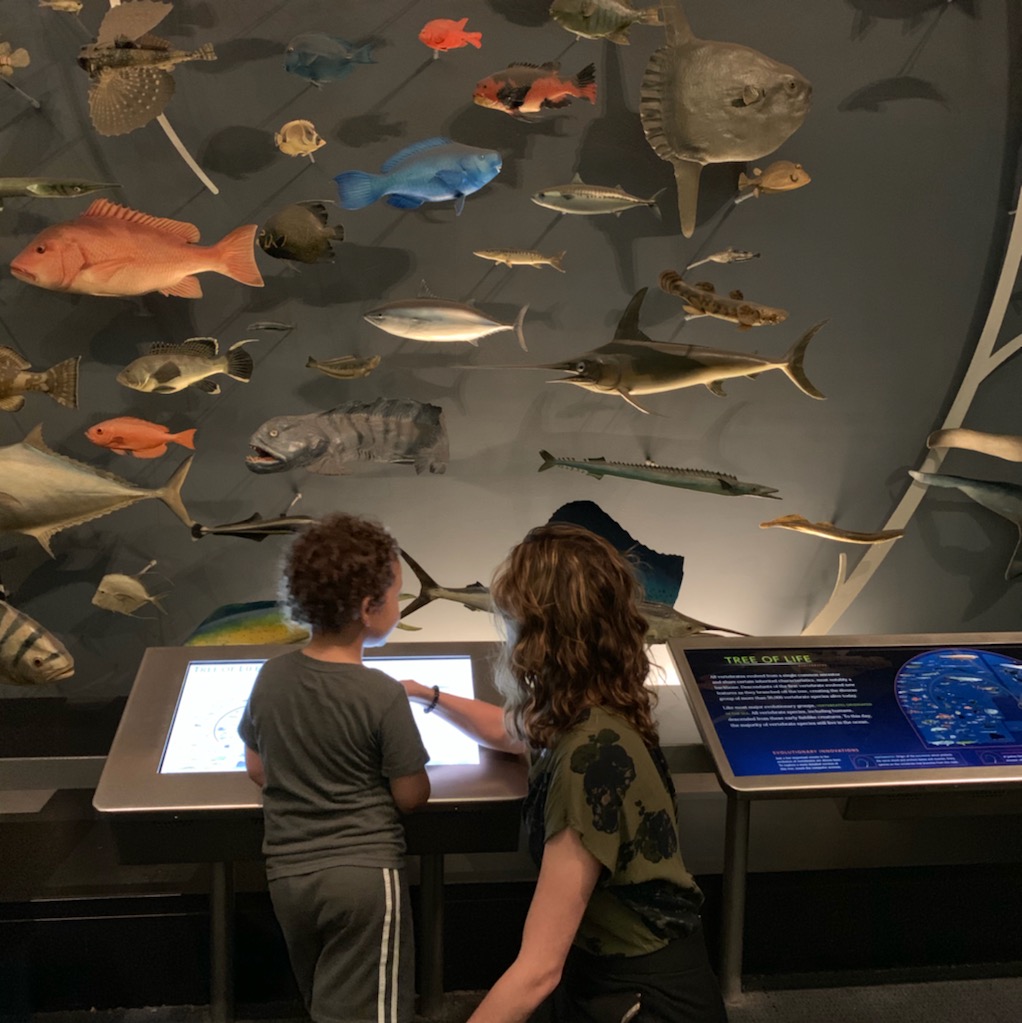

In the Hall of Biodiversity at New York’s American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), 3.5 billion years of evolution are mapped out through 1,500 life-like models. Parents and kids alike examine everything from startling crustaceans to exotic birds with ambitious names.

As a child from outside of Philadelphia, Jacquie Horgan was one of those kids. Years later, she would come back to the same museum — but this time as a doctoral student in Teachers College’s Science Education program, intent on developing science-centered after-school programing to help “kids love science” the way she did throughout childhood.

“It really opened my mind to how remarkable kids are, and how science can just be that source of continued curiosity, creativity and innovation,” says Horgan of her return to AMNH.

With her degree now in hand, Horgan is exploring “an array of possibilities” of how to best pursue this mission next — whether by working in policy, continuing to do research, or pursuing non-profit or university work. Regardless, she will be driven by the belief that, to be effective in the future, science education must properly address and critique the racism that has marred its past — such as faulty applications to justify white supremacy and colonialism, disturbing ventures like the Tuskegee experiments, and less overt behavior that has made the field inhospitable to people of color.

Graduates Gallery 2021

Meet some more of the amazing students who earned degrees from Teachers College this year.

For Horgan, making science more accessible to students of all backgrounds is rooted in “finding a way to educate our youngest students in critically examining science and looking at the ways that science and inequities that are perpetuated in our society are intrinsically connected.” In applying critical race theory to science education, Horgan hopes that young learners can pursue “science pathways as agents of change,” and that more students will feel included enough in the field to continue pursuing it. “My hope — and I know it can happen — is to open up that pathway,” she says.

Horgan cites her dissertation advisor, TC’s Felicia Mensah, Professor of Science and Education, as a key catalyst in her academic journey. “Dr. Mensah is one of the most prolific and amazing people I have ever met in my life,” says Horgan, who served both as Mensah’s course assistant and editorial associate for The Journal of Research in Science Teaching , an experience that allowed Horgan to gain hands-on experience with a variety of students and researchers. “She opened up the scopes of possibilities for me. and also really pushed me. With her mentorship, I was able to develop the critical lens that I have now.”

This work began with Horgan thinking about “frameworks that would have implications for the classroom,” says Mensah, whose teaching philosophy centers upon guiding educators to create environments in which “everything is centered around the student” and teachers engage with the socio-cultural implications of their own identities. For Mensah, this work is critical in fostering educators who can effectively help students “develop their science identities” and “be engaged with science outside of school.”

As Horgan moves forward in her science education career, she acknowledges that some who knew her as a child might be surprised by the path she’s taken. As a kid with social anxiety, she found traditional school difficult. Home-schooling proved to be a better fit, allowing Horgan to “nurture my own science identity.”

“Later on, I was able to look at that retrospectively and say, I wish there was an educator who had noticed what was happening and could have pinned me as not as a child that was just slacking, but someone who had other things to overcome,” says Horgan. “I wasn’t the best student, but I knew I wanted to be a great educator who would be more conscientious about what’s happening in the classroom.”

Which, after all, is a kind of evolution itself.

—Morgan Gilbard