Previously in this space, I have presented the arts as agents of thought-in-action — natural proclivities of the human mind that shape the making and receiving of richly diverse culture(s) — and called for a re-envisioning of schools within clusters of cultural institutions in which the arts serve as extended “texts” for revitalizing learning. In this essay I offer an example of the power and richness of such learning in which a group of high school students speak out using the arts to highlight a social injustice and frame their perception of an ethical failure on the part of adults in their lives.

Early one summer a few years ago, a visit by a Homeland Security detail to New York City’s Heritage School in East Harlem resulted in a female student being escorted from campus. The occurrence was a mystery, the reason not immediately known but subject to conjecture. A swift incursion by the press precipitated a school-wide gag order and police surveillance of the school.

PREACHING ART'S POWER Judith Burton, TC's Macy Professor of Education, believes education that gives the arts real parity can give students a genuine sense of agency. (Photo: TC Archives)

In brief, it emerged that the girl’s family was under a deportation order and had been obliged to attend a Homeland Security interview that morning. However, the girl, who was deeply engaged in a class project, chose not to accompany her parents to the interview, thus setting in motion her removal from the school. She subsequently was flown to a detention center in Texas. With the gag order on students and faculty remaining in effect for the entire summer, no discussions could be held to clarify the situation for the Heritage community or help young people work through their fears and confusion.

At most public schools, the incident might have remained entirely sub rosa, but Heritage, at that time, was not most schools.

Founded in 1996 as a joint effort between New York City and Teachers College, Heritage was an experimental initiative that, for the first decade of its existence, gave the arts full parity within an interdisciplinary curriculum that embraced a broad range of the city’s cultural institutions, whose resources were understood as “texts for learning.”

Founded as a joint effort between New York City and Teachers College, Heritage was an experimental initiative that, for the first decade of its existence, gave the arts full parity within an interdisciplinary curriculum that embraced a broad range of the city’s cultural institutions, whose resources were understood as “texts for learning.”

This was a radical approach, because the arguments intended to place the arts in parity with other disciplines are often pitted against each other and undercut by prevailing narratives of schooling. The arts may be cast as elitist, only for the talented few. It may be argued that creativity and imagination should be subsumed within other disciplines. More disparagingly, the arts may be characterized as frills, unnecessary in schools obsessed with an assessment-driven academic curriculum. In financially strapped times, art is often dismissed as an activity better done after school, in a club, or at home.

The Heritage curriculum refuted all of those arguments. It accommodated a number of extended projects which allowed for considerable border crossing of disciplines. Here, young people learned to draw upon and intermingle multiple strands of experience, engaging in close group collaborations that taught them to dialogue, listen, negotiate and work through contradictions.

The school also was open and responsive to parental needs, input and participation. Community leaders, artists and crafts-persons participated as mentors and advisors. Every student in the school engaged in visual, musical, dance and theater arts learning as disciplinary features of the curriculum. Yearly assessment, as conducted both by Heritage and TC and by standardized testing, revealed that students flourished as a consequence of this dynamic form of learning: In 2005, for example, 90 percent of incoming ninth graders at the school were performing below grade level in math and English. Yet by the end of 10th grade, 83 percent of Heritage students had passed the Math A Regents Exam with a score of 65 or higher, and by the end of 11th grade, 83 percent had passed the English Regents Exam with a score of 65 or higher. And in 2003, in what was a typical year, 42 of the 44 graduating seniors went on to college — 70 percent to four-year institutions, including Columbia, the Honors College at Baruch, and SUNY Binghamton. It was also clear that parents understood more fully how to support their students and that faculty were energized by interactive work with colleagues. Happily, the school was consistently voted one of the best start-up schools during its first decade.

Perhaps the signature quality this approach reinforced among Heritage students was a sense of personal agency in the world. Art education embraced and intermingled the development of personal expressivity and group work, one informing the other. Students were encouraged to engage fully with the materials of each discipline through processes of exploration, reflection and imaginative extension and by drawing upon their aesthetic sensibilities in shaping outcomes that gave presence to their learning. Contexts for teaching and learning were derived from sensitive understandings of student experiences of self and other in the every-day world as shaped through focused dialogue and sharing of ideas.

Perhaps the signature quality this approach reinforced among Heritage students was a sense of personal agency in the world.

All teaching was through dialogue, and students learned to listen and negotiate with each other, and to respect different points of view, understandings and skills.

They also learned to develop and test personal goals for their own learning. Each year student projects were exhibited in the school and also at local venues such as libraries, banks and supermarkets so that the community at large could share in students’ learning. Each year, too, a public symposium was held at which faculty, other educators and interested politicians considered the work of the school. The sessions of the symposium were chaired by students who spoke to how the school was challenging them as learners and preparing them for the future.

As a result, students developed a great deal of autonomy and faith in their own expressive and constructive abilities.

As one example: they began to take the initiative of developing and writing grant proposals offered though the public schools and the City of New York.

In fact, one group’s proposal was selected to create a freestanding sculpture for a well- known bank in lower Manhattan. Excited and proud, the group added more participants and began work.

And then came the Homeland Security visit and their fellow student’s deportation.

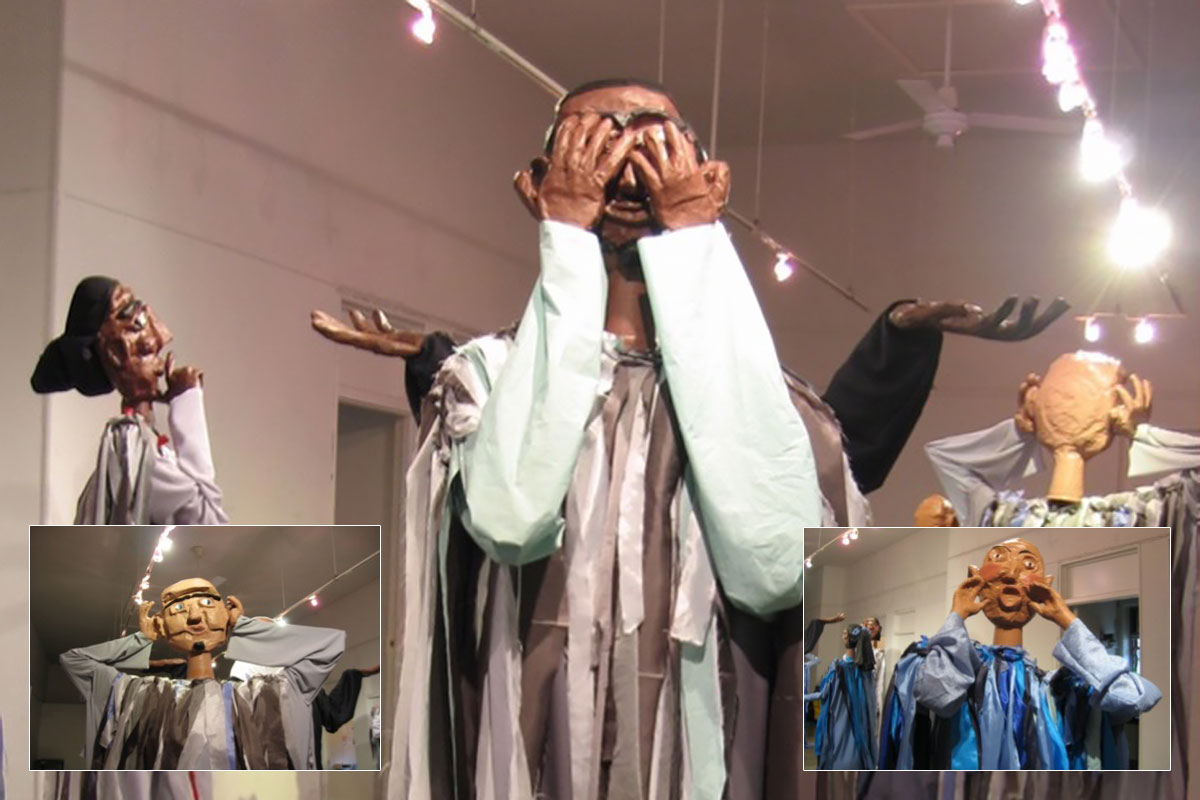

At that point, the group decided to regroup — if not through words then through their art. After much deliberation and adopting the theme of hear no evil, speak no evil and see no evil, which they had worked on previously, they made a group decision to create an installation to express their concerns. Using considerable ingenuity, they dipped into their grant money to buy and collect materials and then designed a free-standing larger than life sculptural group expressing their disquiet with the grown-up world. As the work got underway it attracted offers of help from other students and continued independently of any adult supervision. Three large free-standing figures emerged: one with hands over eyes, another with hands to ears, and a third with hands over mouth. The figures were constructed with chicken-wire and papier-mâché and draped with long strands of cloth. These figures were positioned around a central figure of the girl herself, dressed dramatically in black, with a white head covering. The three surrounding figures were all positioned with their backs to her.

The value of our experiment endures — because the students we prepared are now adults, making their mark upon the world, and because we showed, for a brief time, just how powerfully the arts can transform education, invite new ways of conceiving knowledge and empowering young people to apply their learning toward making a better world.

Upon completing the work, the students elected representatives who were charged with contacting the granting agency and the bank for which the sculpture was intended to explain the new direction their proposal had taken and why. Their idealism was crushed by the adult world: Their petition was rejected and the bank refused to put the work on display.

But hearing of this, the Art & Art Education Program of Teachers College stepped in and offered to display the work in TC’s Macy Art Gallery for an extended period over the summer. In situ, the work powerfully showcased the students’ abilities to marshal their resources and exercise their own agency. It spoke volumes about an event in their lives of great concern to them, in a way that carried their feelings beyond words. The work garnered much attention that summer, with articles appearing in the press and journals. The students wrote poems and narratives, gave interviews and offered presentations about their work.

Some while after the event and the closure of the Macy Art Gallery exhibition, the students sat down to discuss the work and the courage it took to speak out bravely. They credited their school for giving them the autonomy and experience to go it alone. They recalled several class-museum dialogues during which they had encountered the 17th-century Japanese maxim of seeing, hearing and speaking no evil and considered this an appropriate metaphor for “turning a blind eye.” Indeed, in social studies they had discussed the many times that history had been shaped and re-shaped by individuals and groups willing or unwilling to stand their ground at moments of crisis. In mathematics they had also made an extensive study of proportion linked to the aesthetics and uses of the Golden Section — a ratio that creates a pleasing aesthetic through the balance and harmony it creates — in painting, sculpture and architecture.

Also, at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, they had spent time critiquing the model of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais and learned something of the 14th century struggles between France and Great Britain to which this gave testimony. Students recounted how they had reviewed their journals extensively, discussing, combining and rejecting ideas and designs, building their structures bit by bit, and acquiring skills by trial and error. Working without much of a budget, they learned to d use scrap and found materials and “make them speak” in ways that articulated and framed their vision. Students credited their ability to sustain the planning- design-construction process of the work to their in-school extended day periods and their comfort with working in and through collaborative processes understanding that everyone’s contribution added something special to the final outcome.

There were two significant postscripts to this story.

On the positive side, many months after the creation and display of the sculpture, the girl in question was quietly returned to Heritage to complete her education which, happily, she did and subsequently garnered a place at an Ivy League University.

Less happily, after a decade of great success, Heritage came under new leadership and rigid mandates from the City, and turned back to traditional 45 minute in-discipline teaching periods, based on uniform and formalized standards with teacher-proof instruction. The school remains in operation today, but it is an entirely different institution, and no longer the focus of a collaboration with the Arts & Humanities Department at TC.

For those of us who had poured our hearts and souls into making Heritage what it was, this was indeed a dispiriting turn of events. Such are the slings and arrows of American education, which itself, far too often, follows the maxim of seeing, hearing and speaking no evil. But the value of our experiment endures — because the students we prepared are now adults, making their mark upon the world, and because we showed, for a brief time, just how powerfully the arts can transform education, invite new ways of conceiving knowledge and empowering young people to apply their learning toward making a better world.

In the arts, as the filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard said, “It’s not where you take things from — it’s where you take them to.” In these challenging times, perhaps the moment is ripe for others to revisit what we accomplished.

Judith M. Burton is Teachers College’s Macy Professor of Education