Fast Facts

- The U.S. inflation rate hit 8.2 percent in September — the highest seen since the 1980s

- Rising prices for food, gasoline and energy are among the areas where consumers are seeing the most significant day-to-day impact

- Despite efforts to cool inflation by raising rates and the Inflation Reduction Act, new projections solidify the likelihood of a recession within the next 12 months

Potential economic slowdown and rising inflation pose far-reaching challenges for numerous sectors of American life, including education, food access and mental health. Here’s what research tells us could lie ahead.

Inflation vs. Education

From budget strains and school supply costs, inflation is posed to cast a shadow across multiple sectors of education. But for TC’s Samuel Abrams, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Education, “the most salient impact of inflation on education stands to be the pain it causes teachers.”

“For decades, the pay of teachers relative to the pay of other college graduates has been slipping, so much so that teachers across West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma, and Arizona famously walked out in 2018 in protest against this shrinking purchasing power,” reflects Abrams, who is currently serving as a Fulbright Visiting Professor at Finland’s University of Turku.

“Teachers are now in a particularly tough spot for two reasons: first, their pay is determined by contracts negotiated for several years at a time, with only marginal year-to-year adjustments pegged to projected cost-of-living increases; second, teachers, like most workers with modest incomes, spend a disproportionate amount of their paychecks on such essentials as rent and groceries, which have spiked in cost. Inflation has accordingly made the teaching profession both less attractive to those thinking of entering the field and less viable for those already in it.”

Abram’s projections — if realized — could likely collide with the ongoing teacher shortage, meaning that public officials and teacher unions would likely have to work even harder to fill staffing gaps and meet demand.

The Chicago Teachers Union march in fall 2019. (Photo by Charles Edward Miller/Wikimedia)

In addition to inflation’s effect on teachers, student loan debt is continuing to raise challenges for students pursuing higher education, particularly those from lower-socioeconomic backgrounds.

"Most students struggling with debt today are from low income or middle class families,” says Henry Levin, the William Heard Kilpatrick Professor Emeritus of Economics and Education. “These students often use their loans to support family members with expenses.”

As inflation trends upward, the pressure to surreptitiously use more of these loans may be even greater, says Levin, who adds that students frequently utilize their loans for additional expenses, including automobiles, electronics, and necessities.

But students are faced with an even greater challenge in navigating today’s job market, which continues to fluctuate in a post-pandemic world. Graduates, Levin says, often overpredict the simplicity of securing a job, making it even more difficult to account for loans. "Students are remarkably naive regarding the meaning of debt and repayment; they often view the future as far more profitable and immediate upon graduation."

Upon these obstacles, many find themselves asking: ‘what's next?’ According to experts like Levin and Abrams, a predicted “downward push” in spending and purchasing power is near.

Inflation vs. Food Access and Nutrition

Inflation compounds existing inequity in America’s food system, explains two experts from the Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education and Policy: Pamela Koch, the center’s Faculty Director and the College’s Mary Swartz Rose Associate Professor of Nutrition and Education; and Jen Cadenhead, Tisch’s soon-to-be Executive Director.

“The people who are wealthy in this country are going to be just fine. The people who are feeling the brunt of it are the people who are poor and the people who have kids,” says Cadenhead. “After rent, heat, etc., food is the last thing that people pay for, and federal waivers [providing free school meals] have just expired. What does that mean? At the same time that food prices are going up, key government support has fallen away. It’s really going to be very sad.”

But inflation won’t just hit the dinner table. School meal programs will also likely shift to adapt to costs, and with the simultaneous end to the pandemic-era federal program that issued universal free meals, schools will be tasked with combating social stigma, supply chain issues and challenges in maintaining food quality.

“If a family is counting on their kid having the lasagna they love on Thursdays, and that kid doesn’t get that meal, parents are going to be upset.” says Cadenhead, emphasizing that the strength of the system is built on trust.

(Photo: iStock)

“School meals are the healthiest meals that Americans eat. School meals are not what they were 20, 30 years ago. Even if there are differences in services, giving school meals a second look is important,” says Cadenhead, whose research examines the complex relationship between diet and health issues. “It’s really the only place where kids get their fruits and vegetables where people are experiencing food deserts. You can trust school meals.”

Food and nutrition inequity will also likely be further compounded by inflation’s effect on government assistance programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Koch explains: “SNAP benefits are not adequate for eating healthily…and unfortunately, even though the benefits were adjusted to address inflation in 2021, it’s now getting behind again. It can’t adequately support healthy eating.”

But what could alleviate these risks? For nutrition advocates like Koch and Cadenhead, the hope of passing Child Nutrition Reauthorization may be at risk if it fails to happen before this congressional session ends in December. Properly funding food access and nutrition programs would face greater barriers with a fiscally conservative majority, explains Cadenhead. “It shouldn’t be partisan to feed kids.”

Inflation vs. Mental Health

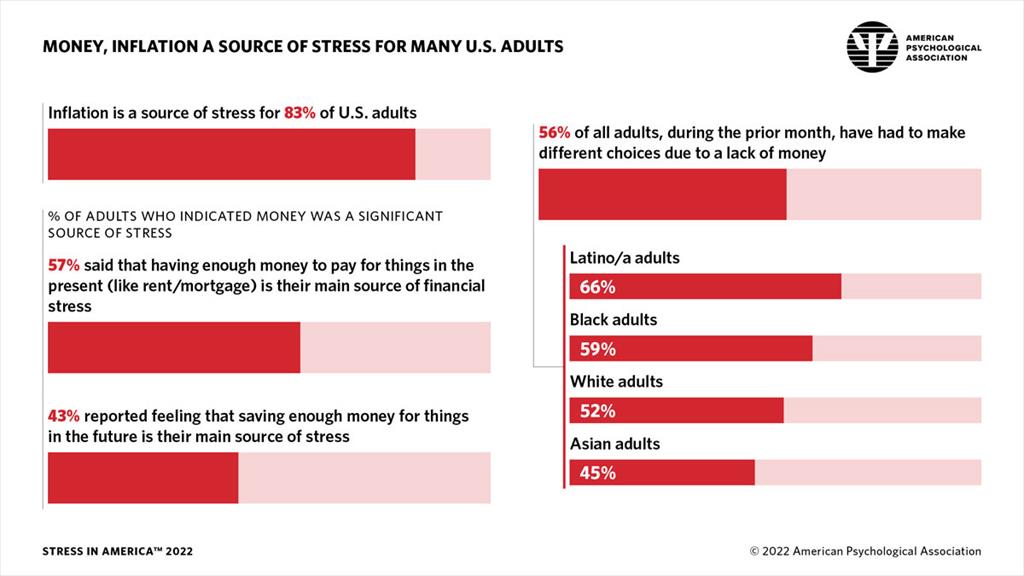

A new survey from the American Psychological Association reports that 83 percent of adults cite inflation as one of their most significant sources of stress. As Americans grapple with a shifting economy, kids are likely to experience compounding effects.

“It’s like anything; when parents have stressors, kids can feel that tension and anxiety,” explains Cindy Huang, Assistant Professor of Counseling Psychology. “When parents are stressed, it impacts how they are with their kids; they might have decreased patience, they might be more irritable. Any of the ways humans show their stress, that transfers to our kids.”

Minimizing the adverse effects of this stress starts with developmentally appropriate communication, Huang advises: “Let them know about what is going on in a way that does not increase anxiety. Stick to the facts. And emphasize that it's not because the child did something.”

Inflation is a source of stress for 83% of U.S. adults, according to new research from the American American Psychological Association.

But when parents fail to communicate in a developmentally appropriate way, children will often respond in two key ways: they’ll internalize the issue, blaming themselves, or they’ll externalize the problem and act out.

“Kids feel what is happening. Period. And when things are vague, meaning they don’t know why their parents are tense, or worried, they may internalize or act out in reaction to their parents’ stress. And that’s how we see this trickle-down effect,” says Huang, noting that financial stress can affect families at all socioeconomic levels.

In addition to openly communicating in a developmentally appropriate way, Huang advises that parents regularly engage in “self-checks” when stressed to help them process their emotions. “Taking a moment to acknowledge how you feel can be a first step,” says Huang. “Parenting is tense enough already and your kid annoyed you by asking for something you can’t give them, and then you snapped at them…Those immediate reactions are part of not realizing how tense you feel.”