Since the 1970s, which marked the era of a new feminist movement and the federal Title IX requiring equal opportunities for women in higher education, there have undeniably been more opportunities for women to teach or launch successful careers in the so-called STEM fields — science, technology, engineering and math — in which a female presence had once been nearly invisible.

Yet to the women who’ve been on the cutting edge of progress in the STEM professions, the storyline of that half century is still dominated by the routine, frustrating obstacles of a culture that continues to be dominated by men. For TC’s Marie L. Miville, Professor of Psychology and Education and Vice Dean for Faculty Affairs, these structural barriers are epitomized by the story she was told by a female professor who landed a prestigious university post and then wasn’t told when department meetings were held – or even given a key to its offices.

Miville, a leading authority on gender and racial differences in academia, said “there are individual success stories, laws that have been passed, and all sorts of scholarship and fellowship programs that have occurred in the last 50 years that have given a lot of individual girls and women a boost up. But sometimes girls and women are finding that still the glass ceiling — some of those structures — are still stubbornly there.”

The tension between the green shoots of progress for women in the STEM fields and the deep structural barriers that remain in place and have discouraged some from pursuing career dreams are at the heart of a new book by Miville and three female co-authors.

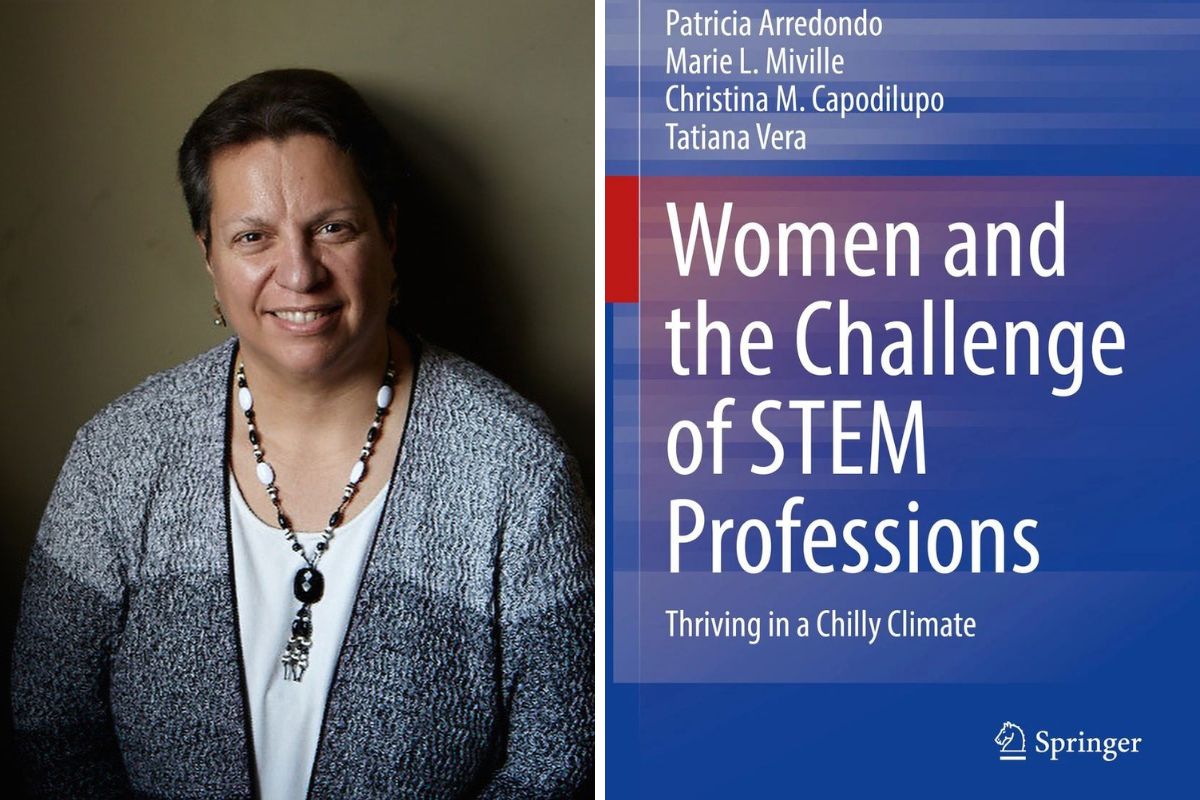

Marie L. Miville, Professor of Psychology and Education and Vice Dean for Faculty Affairs, and her latest book. (Photos courtesy of TC Archives and Springer)

Women And The Challenge of STEM Professions: Thriving In a Chilly Climate, published by Springer, is indeed an overview of the many hurdles faced by female scientists, mathematicians and engineers — particularly in the campus environment — in areas such as advancement, or simply achieving recognition for their work. But the book also places an upbeat emphasis on success stories and positive strategies of women who’ve launched fulfilling careers and found happiness despite those lingering barriers.

Miville said in an interview that the project came about during the depths of the pandemic. It started with discussions she’d been having with Patricia Arredondo, a psychologist based at Arizona State University, around statistics showing that many girls who start their schooling with an interest in the STEM fields eventually abandon them by college, despite the decades-long push for female empowerment.

Miville and Arredondo would go on to strengthen the project’s ties to TC, bringing on alumna Christina Capodilupo — a member of the President’s Advisory Council and an adjunct assistant professor specializing in data research — and then one of Miville’s doctoral students, Tatiana Vera. Vera not only helped organize the effort but brought a much needed youthful perspective about the lingering roadblocks faced by women entering the field. Miville said both the presence of three Latina co-authors — versed in the ways that racial and cultural issues can intersect with gender — and their grounding in psychology aimed to bring some fresh perspectives to the ongoing conversation about the slow pace of progress for women in STEM.

The book’s core case could certainly be made through statistics. It notes that the number of U.S. women in engineering has not increased since the early 2000s and the rate of female deans, department heads, and faculty at universities has hovered at barely more than one-third. But at the center of the book is a focus on the experiences of 10 women and the ups and downs of their careers in STEM.

For example, a postdoctoral researcher named Emma told the authors she felt discouraged from pursuing a traditional career in STEM: “I would have scientific ideas, talk about them with my PI, get little feedback on whether or not they were good. But then I’d hear that they were using those ideas that I had talked about and were being done by someone. I was like, wait a minute. I talked about that with him.”

But Emma also reported finding her path forward with the help of mentorship, which the book finds often was critical for those women who do ultimately find satisfaction in their STEM careers. Other best practices described in the book include strategies for more assertiveness and for overcoming the negativity of their male colleagues whose competitiveness often has the effect of stifling female empowerment.

“I hope girls and women and all the readers take away a hopefulness from the stories that they read,” Miville said of the book. “So it is challenging – but also not just possible but very likely that you can successfully navigate your own pathway to success, wherever that takes you.”