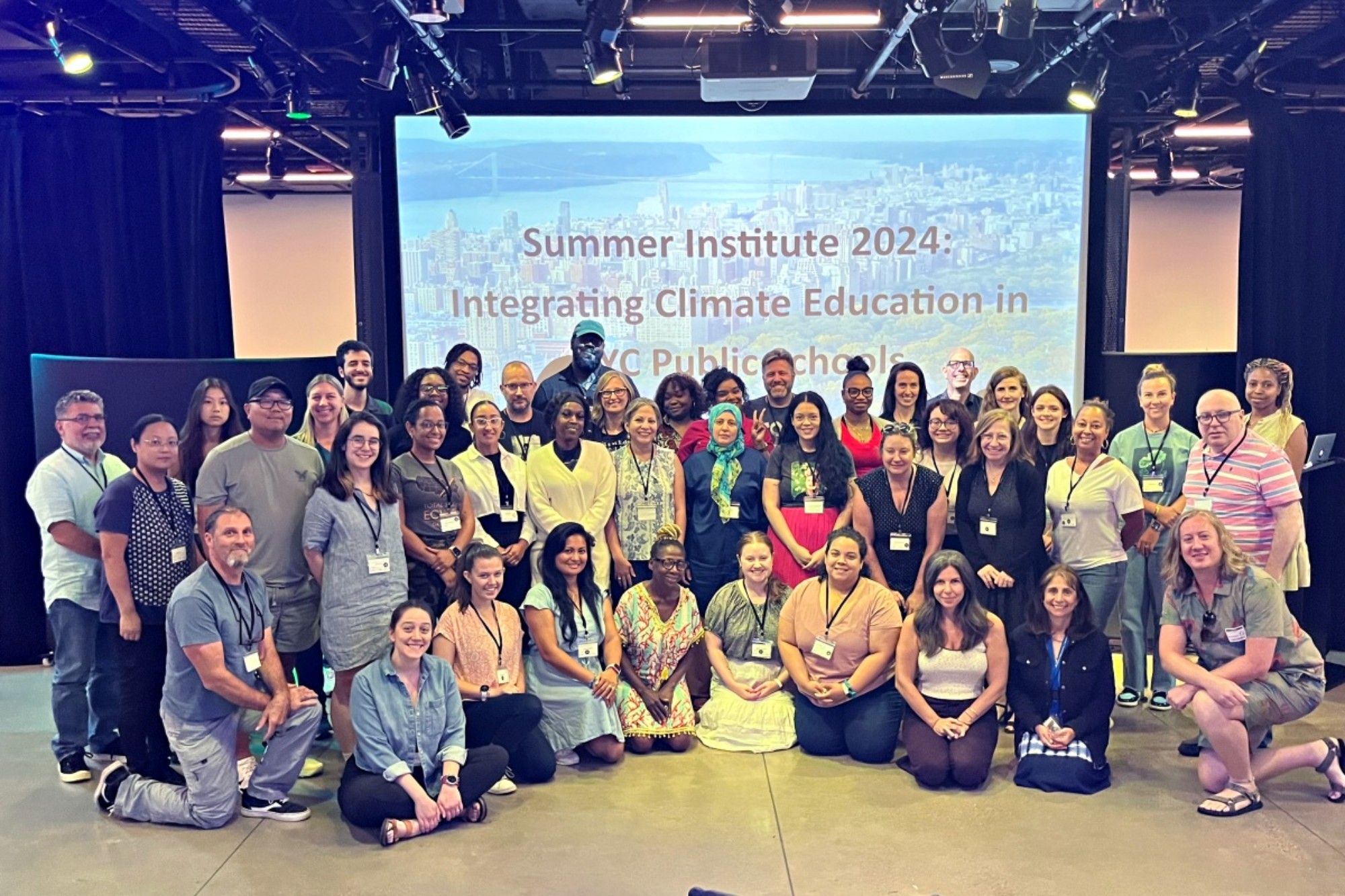

Some of the future’s most critical players to alleviating climate change are still growing up. That’s precisely what drove 40 middle school educators to Teachers College this July to participate in the 2024 Summer Climate Institute: Integrating Climate Education in NYC Public Schools.

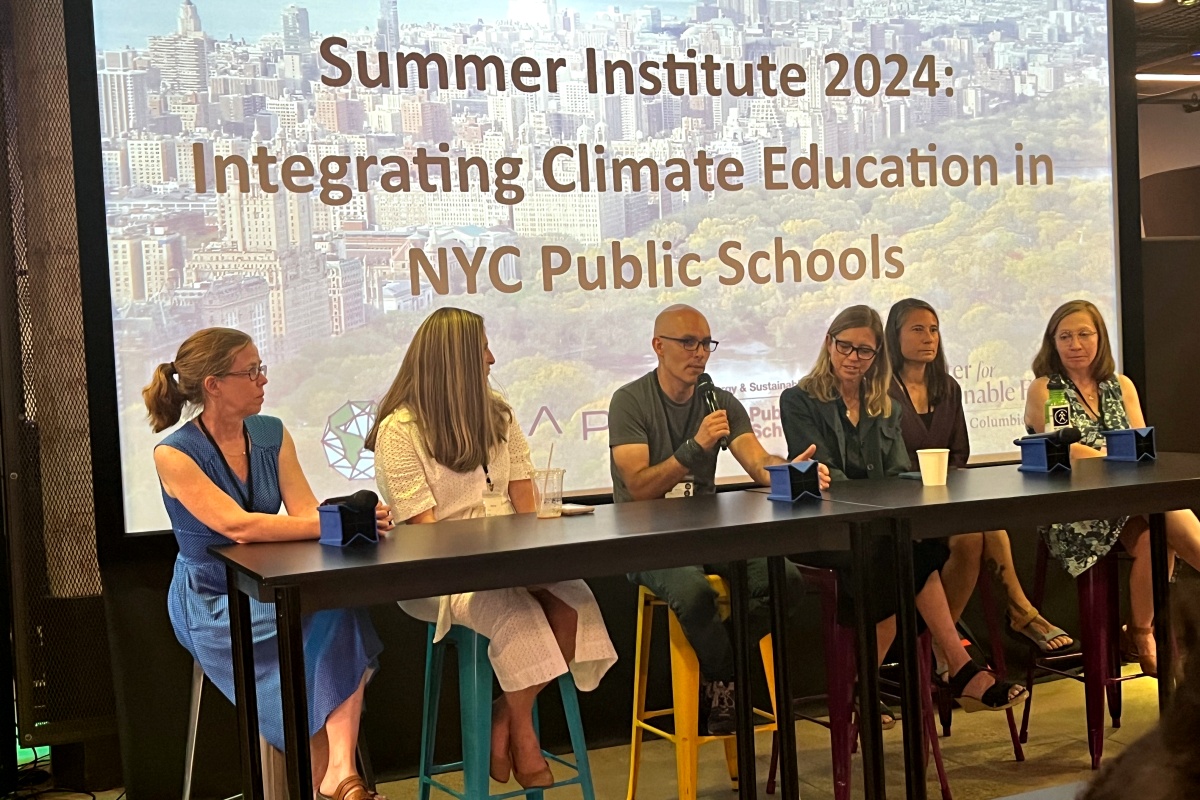

Hosted at the College’s Smith Learning Theater, the week-long professional development program returned to immerse participants in practices of climate change fundamentals, interdisciplinary pedagogy, student engagement and more. A partnership between TC’s Center for Sustainable Futures, the LEAP (Learning the Earth with Artificial Intelligence and Physics) Center at Columbia University, and the Office of Energy and Sustainability in New York City Public Schools (NYCPS), the Institute was created as part of a $25 million National Science Foundation grant in 2021. This year’s programming was the second in an initial, four-year Institute for elementary, middle and high school educators.

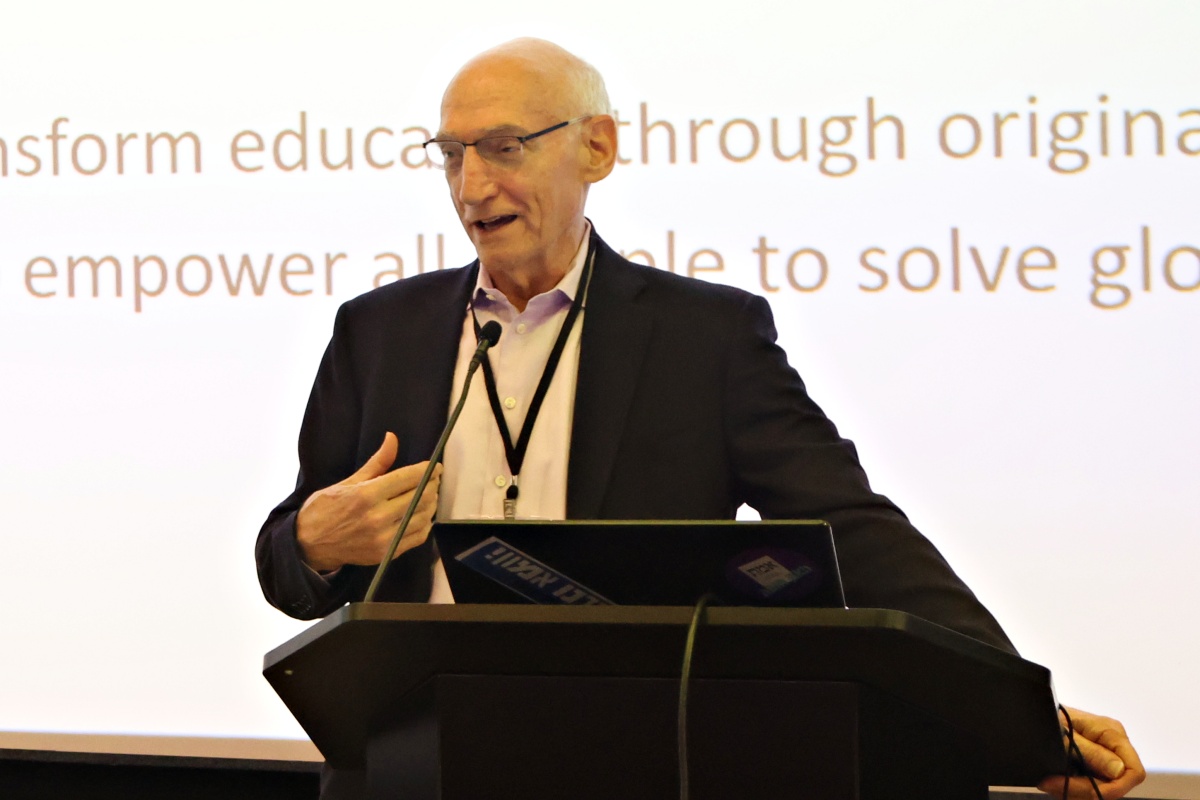

“Education is crucial for mitigating the impacts and risks of climate change, and as guardians of today’s students, teachers and educators play an essential role in preparing them for a challenging future,” said Oren Pizmony-Levy, Associate Professor of International and Comparative Education and Director of the College’s Center for Sustainable Futures. “Our work together in the Summer Climate Institute — as researchers, scientists and educators — continues long after the last workshop, and the teachers who joined us this summer are now part of a robust learning community dedicated to addressing one of the most profound issues of our time.”

Incorporating climate change into everyday learning is nuanced enough. Middle school teachers, the Summer Climate Institute acknowledges, must further contend with a unique set of challenges — most notably, the complexities of “fitting” the topic into an already packed curriculum. Nevertheless, educators walk away from the Summer Climate Institute with a robust understanding of how to integrate culturally-sensitive learning on climate causes, impact and responses into their classroom practice — despite constraints.

“The places to talk about climate are everywhere,” attests Ann Rivet, Associate Director of the Center for Sustainable Futures and Associate Professor of Science Education. Rivet co-designed the Institute’s programming to immerse educators in ways to talk about climate change across art education, English language arts, mathematics, social studies and (of course) science.

This interdisciplinary approach aligns with the College’s efforts to prepare teachers as critical first responders on the front lines. The Public Good Initiative, launched by President Thomas Bailey last year, aims to coalesce scholarship and action across four key areas, including sustainability, the future of teaching, mental health and wellness, and digital innovation.

“We recognize the value of K-12 schools, teachers, students, and their local communities in helping advance solutions for the challenge of climate change and sustainability,” President Bailey told educators in his welcoming remarks. “Together, you will form a learning community as you incorporate the very real challenge of climate change into your classrooms, across a whole range of subject areas…Thank you again for your commitment and your care.”

In addition to cultivating interdisciplinary instruction, teachers can also help students develop the tools needed to effectively contribute to the world around them. “[In middle school,] you’re beginning to see teachers connect knowledge and action in ways you don’t see in elementary school as much,” explains Rivet, also Associate Professor of Science Education. “Here are action-oriented things in their local communities and on the national level that students can do, and teachers can help give them power and agency to do something. We know from research that this approach results in deeper, more meaningful understandings of the concepts that students can then apply elsewhere.”

We’re not going to deal with climate change if the scientists, social scientists and mathematicians aren’t working together.

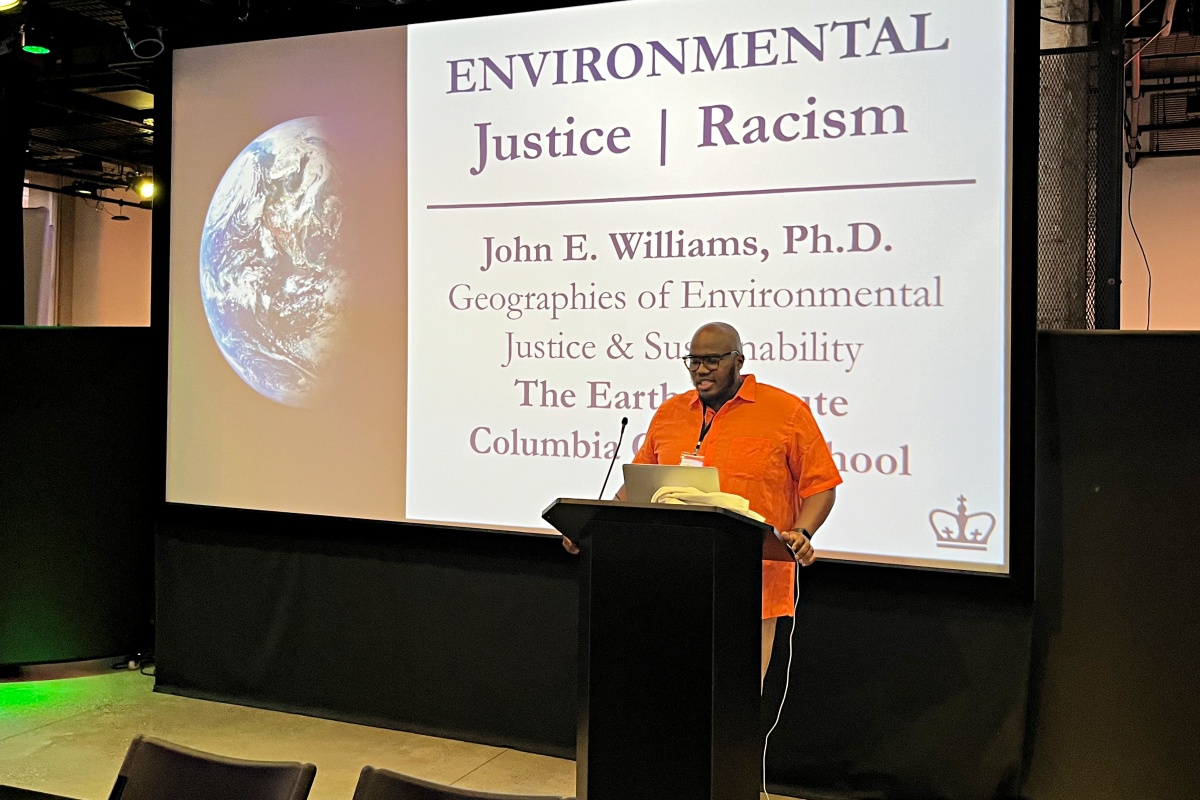

To fully empower students as agents of change, educators must also take a culturally-inclusive approach to climate education — acknowledging the racial and socioeconomic impacts of the crisis in order to more effectively prepare and connect with their students. For New York City public school teachers, this approach is particularly relevant and essential. Nearly 73 percent of its students are economically disadvantaged, and more than 80 percent are children of color. Simultaneously, TC alum John E. Williams (M.A. ’19, Higher and Postsecondary Education) explains, many students deal with the very tangible impacts of environmental racism daily — such as living in the formerly redlined neighborhoods next to the Bronx’s “Asthma Alley.”

“Those topics are hard to talk about, but once you talk about it, people have a better understanding of American history and it helps you understand other parts of life,” explains Williams, who hosted the Institute’s session on environmental racism — drawing from his experience as the Director of Student Affairs and Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion at the Columbia Climate School. “Teachers are creating tomorrow’s climate leaders who will be doing this kind of work. Making connections between policy and the environment helps people understand how we ended up at this place, and environmental justice can help you inform the forefront of decision making. Because as you become a leader, you know that these kinds of decisions made these kinds of problems.”

Discussions of diversity, equity and inclusion permeated more than just Williams’ session — as teachers are consistently confronted with the real-world impacts of climate change on their students, with one educator noting the increasing frequency of climate events like last summer’s extremely unhealthy air quality amid the Canadian wildfires and last September’s extreme flooding in Brooklyn.

“The more teachers understand and are able to talk about climate change more holistically, the more confident they’re going to feel in working with diverse students in this instruction,” explains TC doctoral candidate Christina Torres, a research associate at the Center for Sustainable Futures. “It doesn’t matter how much knowledge you have on climate or pedagogy if you don’t feel empowered to bring it into your classroom or your schools.”

Fueled by dynamic presentations and coaching sessions, we teachers were able to offer support and practical creative imaginings to each other. It's not often I get to have those kinds of community conversations.

The TC, LEAP Columbia and NYC Schools program — a special partnership that allows the Institute to consider the “multidimensional challenges that it takes to implement this in the classroom,” notes Torres — will continue next summer when the Institute opens its doors to high school educators, with intentions to continue and expand the program in the coming years through additional funding.

“We recognize both the need and the opportunity to build a scalable and sustainable model to support New York City teachers around this,” says Pizmony-Levy, noting that Institute leaders are looking for additional support to continue and expand the Institute. “Forty teachers is a drop in the bucket across NYC schools. We’re taking this as an opportunity to better understand how to help the teachers across the city moving forward.”

A Teacher’s Perspective

Meet Jeremy Amar

Media Arts Teacher, Corona Arts & Sciences Academy

What’s Next: Collaborating with 10 colleagues from the Summer Climate Institute on developing creative ways to incorporate climate science across a variety of subjects, including media arts — a discipline Amar sees as essential to helping students express themselves and explore the world around them.