Just over 70 years after Brown v Board of Education, educational equity is still elusive, even more so after a rise in book bans and the end of race-based affirmative action in college admissions. Offering inspiration for the future by looking to the past, this year’s Phyllis L. Kossoff Lecture on Education and Policy, given by Dr. Crystal R. Sanders, draws connections between the historical struggle for high quality education and the current fight for fair and equitable schooling.

Established in 2007 by distinguished alum Phyllis L. Kossoff, the lecture series has provided a platform to further critical conversations on education, policy and research. For the 10th lecture, the first since Kossoff’s passing in 2022, Sanders, Associate Professor of African American Studies at Emory University College of Arts and Sciences, gave an illuminating lecture on an educational migration that occurred during the Jim Crow era.

Her talk, “A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners and Graduate Education During the Era of Legal Segregation,” outlined the myriad difficulties Black Southerners faced as they sought out graduate education in often hostile environments. She focused specifically on “segregation scholarships,” a term originated by Sanders that describes state funding given to Black students to support their studies at Northern colleges and universities in order to maintain segregation in the South.

Find takeaways from her lecture — a preview of her upcoming book, A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUs — below.

(Photo courtesy of Sanders)

Many Black scholars, especially recipients of segregation scholarships, came to TC for their studies

It’s unknown precisely how many Black students came to TC on a segregation scholarship however, according to Sanders, the College’s summer continuing studies program was one of the most popular during that time period. Being a top graduate school of education with a history of accepting Black students certainly played a role, but Sanders cites proximity to Harlem and Mabel Carney’s, head of TC’s Rural Education Department from 1918 to 1941, course on Negro Education as a major draw for scholars.

Existing relationships with Southern educators combined with a willingness to accept Black students, Sanders noted, made TC a top choice for Black educators at the time. The work of professors like Arthur Linden, who ran summer courses for degree credit in Asheville, N.C., further expanded TC’s reach in the South and made higher education more accessible to Southern scholars.

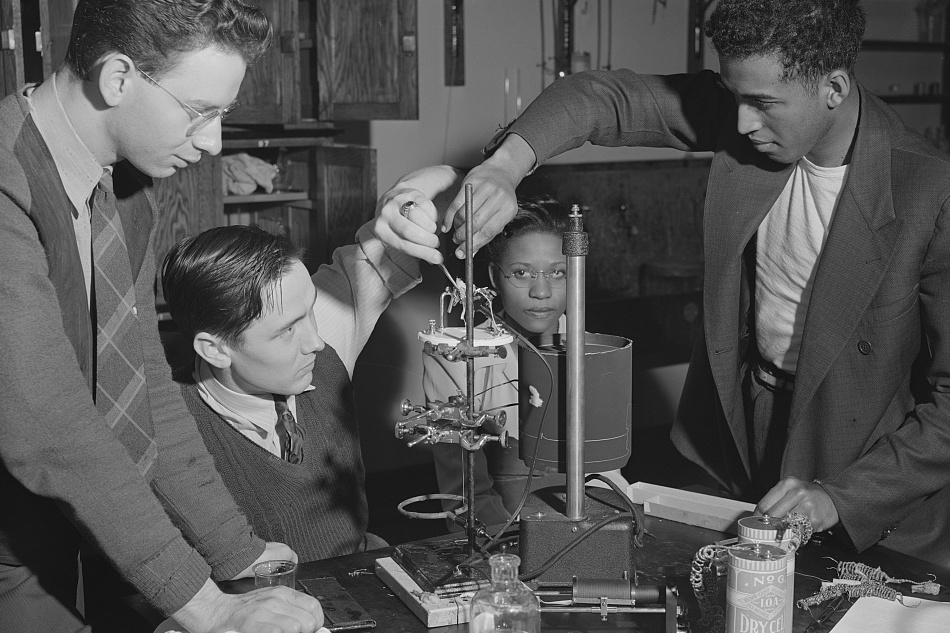

Post-graduate students conducting a lab experiment, 1942. From left to right: J.S. Newcomer, A.E. Bell, Hiss Trondailer Jones and Samuel Massie. (Photo: FAS/OWI Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Segregation Scholarships offered great opportunities, at a high cost

As explained by Sanders, during legal segregation, virtually all Southern schools with graduate programs refused to accept Black students, while Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were often unable to offer graduate programs due to lack of funding from state legislatures. This forced Black students to journey North for their education which was often out of reach financially. To offset the costs, students leveraged the “separate but equal” doctrine, pushing Southern states to pay for Black students forced to study out of state. Sixteen Southern states started segregation scholarship programs between 1921 and 1948, despite these programs being deemed unconstitutional in 1938.

Even though scholarships offered needed opportunity, “most of [the recipients] felt that there was a disadvantage professionally, [and] a disadvantage personally,” said Sanders. Professional degrees received out of state were met with undue scrutiny and created more hurdles, such as law students who had to study legal codes for two states at one time. Students also encountered racism in the North, struggled to find housing and dealt with extreme pressure to “behave properly” at their new school. The isolation students felt was compounded by their inability to visit home during their studies, as scholarships often didn’t cover basic living expenses, let alone travel expenses for a trip home.

Howard University students on campus, 1942 (Photo: Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

Pushing Black scholars to study at Northern institutions created an enormous debt at Southern HBCUs

While they have a rich legacy, many HBCUs have crumbling buildings and small endowments. Consistent underfunding plays a major role in this decay — over the course of 33 years, 18 state-run land-grant HBCUs were underfunded by $12.3 billion, adjusted for inflation — as does the legacy of segregation scholarships. Rather than being paid by the state, scholarships were instead taken from the operating budget of Black colleges and universities.

While individual scholarships weren’t substantial enough to cover each student’s needs, it still cost schools an incredible sum. By Sanders’s calculations, just one year of segregation scholarships cost Mississippi HBCUs $5.3 million dollars in today’s money and they ran scholarships for 20 years. Sanders argued that those funds could have been used to update infrastructure, attract faculty, and support new research. Instead, HBCUs had to foot the bill of segregationist policies.

To address this lack, Sanders proposes that state governments give HBCUs “equity funding” by making an endowment contribution that matches the amount of money spent by each school on segregation scholarships, adjusted for inflation. “Nothing less is acceptable,” she said.

Despite the financial difficulties, isolation and racism scholars faced, they fought for their education out of a desire for a better life, Sanders explains. When they returned home with their hard-earned degrees, graduates set about “using their credentials and their training to create the type of world they want in these Southern communities,” said Sanders.

Sander’s forthcoming book, A Forgotten Migration: Black Southerners, Segregation Scholarships, and the Debt Owed to Public HBCUs, will be published in October of this year.