Writing for the IRB is different from writing for academic papers, courses, and descriptive works. This blog outlines the 5 different types of IRB writers and respective supporting resources (like contacting Teachers College Graduate Writing Center).

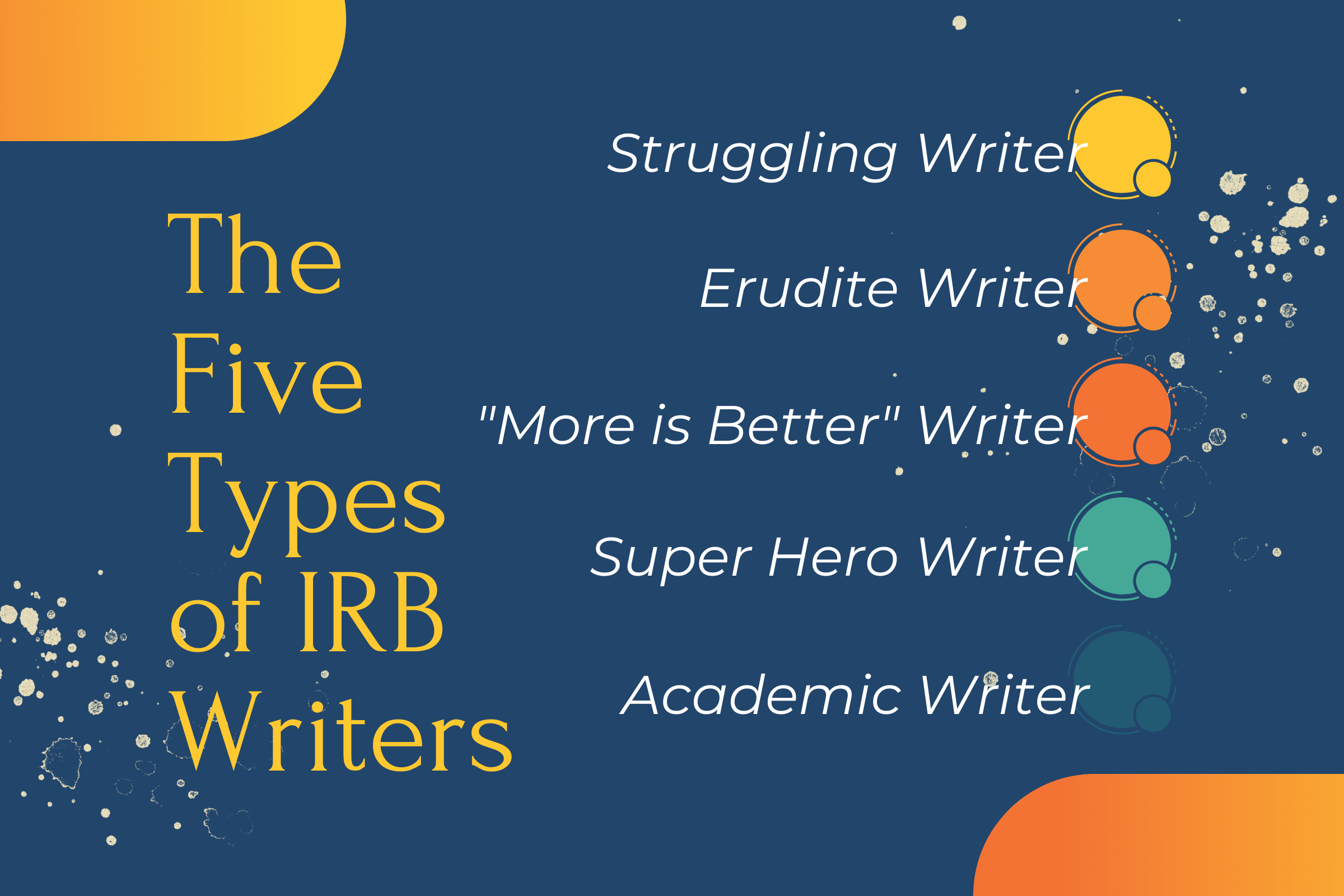

Typically, there are five types of writers TC IRB administrators encounter when reviewing IRB documents: the struggling writer, the erudite writer, the “more is better'' writer, the superhero writer, and the academic writer. Below, you will find the description of each, and resources that can help improve your IRB protocol submission writing.

The Struggling Writer

These writers struggle with grammar, spelling, and punctuation. The documents submitted by struggling writers are often difficult to read and require a large amount of revision.

- Keep in mind: If the IRB reviewer cannot understand what is being asked of participants, the IRB cannot assess the risk of the study or work to mitigate it.

- Resource: Visit 5 Tips for Effective Proofreading to elevate your writing.

The Erudite Writer

These writers typically do well but write far above the general population's understanding. For example, the consent form should clearly convey the study purpose and what is expected from a study participant.

- Keep in mind: For this kind of writer, it is recommended to focus on information-sharing, avoiding jargon, and keeping the writing simple.

- Resource: Visit Writing for an IRB Review to review writing for your audience with cultural competence and evaluate your document’s readability.

The “More is Better” Writer

These writers include far too much information in their documents. These writers typically submit multiple-page documents, explaining every single study activity in minute detail. Too much detail can be overwhelming to an individual interested in your study, and they may become distressed, bored, or experience cognitive overload.

- Keep in mind: If a participant cannot understand what is asked of them, how can they fully consent to be in the study? To support participant understanding, especially if the study is complex, include bullet points in the consent form, use examples, or make references like, "wearing this device is similar to wearing a watch on your wrist.

Resource: 7 Tips for Clear and Concise Writing

The Superhero Writer

These writers tend to think that their study can “save the world.” This view is often problematic, as these writers often overstate study benefits and downplay the risks. These writers need to remember that their research is typically for testing, inquiry, or exploration and that they do not know how their study will end or what their findings will reveal.

- Keep in mind: A general rule of thumb is to inform potential participants about the study risks in a clear and concise way and not to cheer or promote participation. Every potential participant has the right to say “no,” even after they have received information or expressed interest.

- Resource: Understanding Potential Risks for Human Subjects Research

The Academic Writer

These writers often do well when writing for class assignments, journal writing in their field, and overall are content-knowledge specialists. However, this type of writer struggles with taking their elevated knowledge and explaining it to a general audience.

- Keep in mind: When writing, consider using examples that make the study relatable to the general audience. Ask yourself, can my neighbor, grandma, niece, or colleague understand my study activities? If the answer is yes, then your content is written at the appropriate level for your audience.

- Resource: Write for your audience.

When writing your IRB protocol, you can use the TC Reviewer Questions as a guide for what IRB reviewers will look for in your protocol.

For more information on Stephanie's engagement with the IRB and her internship, please review our webpage: Research Writing & Ethics Interns.