In this blog post, Hira Shahbaz, Research Writing & Ethics intern continues her blog series on Culturally Responsive Research in a 45-minute interview with a member of the Teachers College research community. Her interviewee, Jonthon Coulson, offered interculturally sensitive ways to engage in research across borders.

Jonthon Coulson is a doctoral candidate in the Curriculum & Teaching department of Teachers College, Columbia University. He is currently based in Indonesia, where he explores educational spaces continually shaped by coloniality and increasingly affected by both foreign entrants and governmental decentralization. His particular focus is on the role pedagogy plays in the forging of identities and the sustenance and revitalization of local wisdom.

Path to Research Questions

Jonthon is currently conducting research with Bajau people he first encountered while completing a writing fellowship in Indonesia. Though the origins of the Bajau people remain unknown, the Bajau continue to reside in parts of Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and East Timor. "It's an open question," Jonthon said, "but what's clear is that they have been traveling around on boats and living a mostly seafaring nomadic lifestyle until about 100 years ago, and especially at the onset of the post-colonial era, when nations used schools and their militaries to began to sedentarize Bajau communities and otherwise exercise power in their periphery." Jonthon explained the tensions between state-imposed education and the knowledge transmission methods of the Bajau people, stating "the people in the [Bajau] community are teachers by way of cultural upbringing, but because [the Bajau] "didn't go to school, don't get the degrees that allow them to teach," they are largely restricted from teaching in schools. Instead, teachers are outsourced from land-based communities.

These teachers often have preconceptions and biases about the Bajau people. "Plenty of them have a very strong deficit view lens, viewing the Bajau as illiterate, incapable, or otherwise stupid or backward." He told me, "in many Bajau communities assigned teachers are just in absentia. Once they get placed there, they just don't come. They have a thousand reasons not to go out to a floating village in the middle of the ocean." This observation led Jonthon to ponder and eventually focus his research on the Bajau episteme, "how folks there make use of the [school] buildings and how they educate outside of those buildings and [...] to think with them about what it will mean in the next generation for them to go to college and get that degree, get that certificate, to be able to teach in their own community, for Bajau kids to be taught by Bajau people." He posited the question, "How will they do that in the face of a national curriculum and a national examination in ways that are still sustaining or revitalizing their cultural wisdom?"

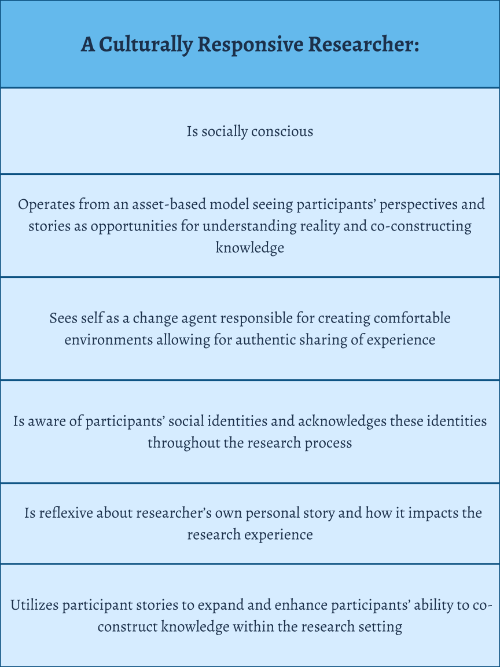

Sustaining and revitalizing cultural wisdom is a critical tenet in culturally responsive research. Berryman et al. (2013) argue that research frameworks of the West have historically "given little regard to participants' rights to initiate, contribute, critique, or evaluate research," promoting the power to define to groups of outsiders who subsequently "re-story and ‘other’" participants (Berryman et al., 2013, pp. 3). Students interested in international research may consider the following:

Accessible Infographic of A Culturally Responsive Researcher

IRB Preparation & Submission

Jonthon spoke about his strategies for preparing a research protocol. "My process of filling out IRBs has been an iterative attempt at renegotiating power relationships between my participants, my co-conspirators, and powerful institutions," he told me. He shared insight gleaned from a qualitative research methods course at TC: "[We] read a paper by Professor Knight-Manuel et al.… [which] talked about having things in size ten font, what it means to have an undocumented person sign a document, all these various contexts in which it's like this document of power brings with it so many assumptions that affect to negate whole ways of being, eliminate whole fields of potential participants in research and thus whittle away at our ability to know." Jonthon spoke of how this course impacted his own IRB consent process: "I made it clear in my [IRB] documents that I have forms that I can hand out to people but that I will read through the forms with people while they are being audio or video recorded and that they can give their consent verbally." Jonthon also back-translates his materials from Indonesian and writes in vignettes.

Insights to Minimize Extractive Research

Berryman et al. posit that "being culturally responsive requires the researcher to develop context within which the researched community can define, in their own ways, the terms for engaging, relating, and interacting in the co-creation of new knowledge" (Berryman et al. 2013, p. 4). Jonthon offered insights on how to promote a collaborative process of knowledge creation and minimize extractive research, stating, "Let people see what you're writing… make it clear to people who you are, why you're there, have conversations about your identity before you start hitting the record button and putting people on the spot." Elevating opportunities for foreign researchers, too, is essential. He explained, "How are you trying to find ways to put them on budgets and funding so that they can be engaged in the same kinds of research as you, even if they don't necessarily have national access? When publication opportunities present themselves, are you the first author all the time, or do you find ways to share and share alike? Are you willing to jump in and be an editor for their paper or to review stuff that your friends have written, even though you're not going to be listed as an author, so that they can get the credentialing they need to rise in their institutions?" He remarked that, "one would hope that if I were to become known in my small niche of the academic world, some of the other people in that conversation would be networked similarly." In closing out his thoughts, Jonthon offered this sentiment: "The best way to combat epistemicide is for academics to bring people together and set some ground rules for talking about how to work together and to be active about the preservation of knowledge without needing to coordinate all of the activity."

Advice for Future International Researchers

Jonthon posited the following advice to students interested in conducting international research: Be as honest and transparent as you can in your documents. “Don't hesitate to reach out to Myra and to other members of the team, especially the IRB interns who are students just like you, to have conversations." He also noted that "To the extent that you're going to use a protocol template, be mindful of the fact that you're making promises to an institution, not only on your own behalf, but also on the behalf of whoever would be willing to share their time and to trust you with their world." Flexibility, too, is vital: "The documents that you do submit… be ready to make changes and to amend and do whatever else on the back end that actually happens in the work that you do, because your ethical compass necessitates you do so. Take the time to write the amendment." Students interested in conducting international research should remember that upholding the rights and welfare of human subjects is a fundamental tenet of responsible research and the IRB office offers guidance to ensure students are compliant.

Further Reading on Culturally Responsive Research

- Culturally Responsive Methodologies, by Mere Berryman, Suzanne SooHoo, and Ann Nevin

- Decolonizing Methodologies, by Linda Tuhiwai Smith

- Ethics in social science research, by Maria K. E. Lahman

References

Berryman M., SooHoo S. & Nevin A. (2013). Culturally responsive methodologies (1st ed.). Emerald.

Rodriguez, Katrina & Schwartz, Jana & Lahman, Maria & Geist, Monica. (2011). Culturally Responsive Focus Groups: Reframing the Research Experience to Focus on Participants. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 10. 10.1177/160940691101000407.