Methodologies of international large-scale assessments (ILSAs), and ideologies of the international organizations (IOs) that support them are abundantly studied. However, their links are not well understood. For instance, do IOs with different education doctrines support ILSAs that follow different designs? And if so, do these differently designed ILSAs produce divergent data about the effectiveness of education policies, leading to divergent policy directives and decisions? Framed by statistical constructivism, an article by Manuel Cardoso in Comparative Education Review tackles those questions by describing two interrelated phenomena.

First, documents from OECD/PISA and UNESCO/TERCE show how IOs’ doctrines about the value of education, based on either Human Capital Theory or Human Rights, respectively, shape the design of the ILSAs they support. UNESCO, seeing education as a human right and therefore autonomous from the economy, follows “the grammar of schooling” that involves curricula and grades when designing assessments like TERCE, targeting 6th grade, typically the end of primary school. Meanwhile, PISA, consistent with human capital theory and OECD’s history of adult literacy surveys focused on human capital stocks (IALS/ALL, PIAAC), measures human capital flows by targeting 15-year-olds, at the start of the working population age.

Second, the paper presents quantitative analyses for four Latin American countries (Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Peru), in three assessment domains: reading, science and mathematics. These analyses compare results from PISA and TERCE within each country and domain, showing that differently designed ILSAs disagree on the effectiveness of a specific policy, namely grade retention: PISA, the age-based assessment inspired by human capital theory, yields an achievement gap between repeaters and non-repeaters that doubles that of TERCE, the grade-based assessment inspired by human rights-based approaches. The differences are systematic, substantial, and statistically significant in all twelve cross-assessment comparisons.

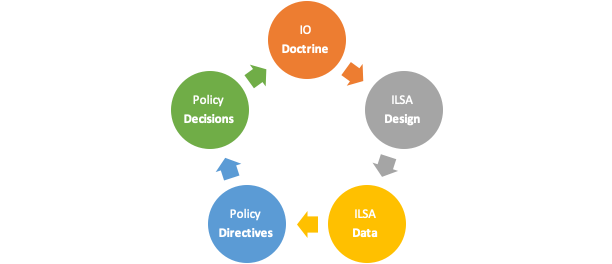

These findings warrant further research. Divergent empirical results could potentially incentivize different education policies, reinforce IOs’ initial policy biases and provide perverse incentives for countries to modulate retention rates or join an ILSA on spurious motivations. Similarly, these findings reinforce IOs’ biases: education policy analyses inspired by human capital theory have historically seen grade retention as “internal inefficiency”; meanwhile, UNESCO sometimes deems grade repetition as a student’s right, particularly in developing countries. In summary, IOs’ educational doctrines shape ILSA designs, which yield different data, potentially inspiring divergent policy directives at the global level and policy decisions at the country level.

Read the full article here.

This article was written as part of the Doctoral Seminar on Academic Writing and Publishing.