In October 1997, in televised testimony before President Clinton’s Advisory Board on Race, the multicultural psychologist Derald Wing Sue urged Americans to conduct “an honest examination of racial prejudices, racial stereotyping and racial discrimination” and accept “responsibility for changing ourselves, our institutions and our society.”

Midway through, he dropped the we and our.

“One of the great difficulties with white Americans . . . is that they perceive and experience themselves as moral, decent and fair people — and indeed, they are,” said Sue, whose father emigrated from China to the United States. “Thus, they fail to realize that their beliefs and actions may be discriminatory.” For society to change, he declared, white people must undergo “a personal awakening” and work to “root out these biases and unwarranted assumptions related to race, culture and ethnicity.”

JOURNEY OF SELF-DISCOVERY Sue overcame shame to embrace his Chinese heritage. (Photo: Bill Cardoni)

Sue took pains in his remarks not to blame whites. People are not born racist, he said, but become so “through a painful process of social conditioning.” Yet he was deluged with angry mail, ranging from accusations that he was a “racist of a different color” to threats that his “tenure on this earth” would be “limited.”

“I was stunned,” he recalls. “What I said seemed so mild and was all vetted by the Clinton staff. But my wife, Paulina, said, ‘You’ve been living in a bubble, speaking to other academics. You need to get out there and talk to the public.’”

It was a turning point for Sue, the beginning of his metamorphosis from change agent in his field to a man on a mission to reveal — not to the haters, but to the more reasonable people who vehemently denied the reality he described — how people of color experience racism on a daily basis.

WAKEUP CALL Sue’s 1997 testimony about racial prejudice in America prompted a flood of angry mail and his decision to begin speaking directly to the public.

For some time, he had been pondering the concept of “microaggressions,” a term coined in 1970 by Chester Pierce, a black psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School (and the first African American full professor at Massachusetts General Hospital) to describe the daily insults and dismissals endured by black Americans at the hands of whites. The idea of microaggressions hadn’t gained traction, but for Sue, who, as a youngster, had been shamed by one teacher for speaking Chinese and encouraged by another to study math because “you people are good at that,” it resonated. “I thought, could all these things that I’ve been experiencing be microaggressions? And I began to dissect the meaning of the term. It comes from a person who thinks they mean well, but there is a meta-communication, an invalidation, that’s especially disturbing to the recipient because it’s outside the perpetrator’s awareness. And when I talked to people of color, they understood exactly what I was saying. I didn’t have to explain it.”

I thought, could all these things I've been experiencing be microaggressions? And people of color understood exactly what I was saying. I didn't have to explain it.

—Derald Wing Sue

In the mid-2000s, Sue, Professor of Psychology & Education, and his Teachers College students began reading personal narratives and combing the literature on racism to catalogue microaggressions, which they redefined as the “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.”

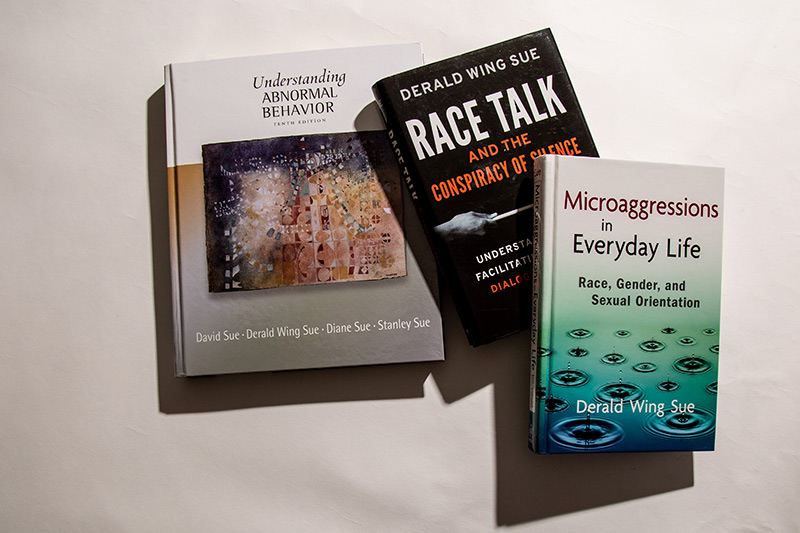

GOLD STANDARDS Sue's books are foundational in multicultural psychology – and Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientations has helped vault him to rock-star status. (Photo: Bill Cardoni)

Microaggressions differ from ordinary expressions of incivility, Sue has since argued, in that they are “continual in the lives of people of color . . . cumulative in nature . . . constant reminders of the recipient’s second-class status in society . . . and symbolic of past injustices directed toward people of color.” And because microaggressions reflect and reinforce society’s existing power structure, only white people, who are dominant, can commit them.

Here is a sampling from the “taxonomy” of microaggressions, quoting directly from the paper that Sue and his students published in 2007 in the journal American Psychologist:

THEME: Alien in their own land (when Asian Americans and Latino Americans are assumed to be foreign-born).

MICROAGGRESSION: “Where are you from?” “Where were you born?” “You speak good English.”

MESSAGE: You are not American.

THEME: Myth of meritocracy (statements which assert that race does not play a role in life successes).

MICROAGGRESSIONS: “I believe the most qualified person should get the job.” “Everyone can succeed in this society, if they work hard enough.”

MESSAGE: People of color are given extra unfair benefits because of their race. People of color are lazy and/or incompetent and need to work harder.

The impact of this work, and of Sue’s subsequent book, Microaggressions In Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation, has been seismic. The 2007 paper has received some 3,700 citations on Google Scholar, and Sue’s work overall has been cited 41,000 times. There have been over 25,000 publications on microaggressions, most since 2007, spanning psychology, business, law, sociology, education and political science. The Merriam-Webster dictionary added the word “microaggression” in 2017.

Meanwhile, Sue has soared to a rock-star status that few academics ever attain. He has logged countless miles to address conventions and meetings, to conduct trainings for corporations, universities and other organizations, and to speak on television and radio. His books have been translated into several languages. He advises a UNESCO effort to foster racial, ethnic and multicultural tolerance among children.

FINDING HIS VOICE As a young faculty member at the University of California at Berkeley, Sue participated in the Third World Liberation movement, a five-month strike by minority students that helped establish the field of ethnic studies. (Photo: Garth Eliassen / Getty Images)

In 2011, in a 40-page tribute in the journal The Counseling Psychologist, Thomas Parham, an authority on racial identity development, wrote that Sue has “literally changed the face of the psychology and counseling professions” through “a Martin Luther King-like call to serve people of color.”

This past summer, the American Psychological Association presented Sue with its Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contributions to Psychology, the highest honor it bestows. Past recipients include B.F. Skinner, Kenneth Clark, Judith Rodin, Albert Bandura, Beverly Daniel Tatum and Martin Seligman. At the APA annual meeting, APA President Rosie Phillips Davis told Sue that he has “made the invisible, visible.”

And at 77, Sue isn’t slowing down. This year, he and his students published a much-discussed paper on “microinterventions” — the powerful real-life responses of ordinary people to microaggressions — that provides “a strategic framework” for moving “beyond coping and survival to concrete action steps and dialogues.” The TC team was given a two-hour slot to discuss their work at this summer’s APA meeting, and the journal The Counseling Psychologist has approved their proposal to produce a 130-page manuscript on microinterventions.

Where He’s Coming From

One of Sue’s favorite responses, when people have complimented him on his own English, is, “Thanks, I should — I was born here.”

Still, he’s traveled a long way.

He grew up in poverty in Portland, Oregon, where his family lived on welfare briefly and picked beans and berries to supplement their income. Sue and his siblings were high achievers (all four brothers became psychologists), with Derald winning a statewide essay contest and becoming the first in his family to earn a Ph.D.

At some point, I changed – I realized, it's white ethnocentrism, or white supremacy, that's the enemy, not white people – and that has lowered resistance to me.

—Derald Wing Sue

Yet while his parents were proud of their Chinese heritage, he felt shame. After his elementary school teacher admonished him, “You’re in the United States — speak English!” he told his mother he would never speak Chinese again “because that’s why people don’t like us.”

Sue’s political awakening owed much to his sense of kinship with black people. In grade school, he sided with black children when they were teased “because I had been teased, too,” and eventually he, too, identified as non-white. In college, his heroes were Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Huey Newton and H. Rap Brown — “because of their ability to speak out so forcefully about prejudice and oppression.”

BROTHER ACT Sue’s three brothers (including Stanley, with whom he founded the Asian American Psychological Association) are also psychologists. He has co-authored books with all of them. (Photo: Bill Cardoni)

He channeled his own activism into changing academia and psychology. As a young faculty member at the University of California at Berkeley, Sue participated in the Third World Liberation movement, a five-month strike by minority students that ultimately helped establish the field of ethnic studies. In 1972, he and his brother Stanley cofounded the Asian American Psychological Association, and in 1981, he and his brother David published Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice, now standard in most multicultural counseling programs.

And in 1999, in the field’s equivalent to Martin Luther nailing his 95 theses to a church door, Sue and others cofounded the National Multicultural Conference and Summit, an independent group sponsored by four divisions of the American Psychological Association. The conference’s stated purpose is “to remind us that psychologists must always be mindful of the impact of discriminatory environments and that we ourselves are not exempt from discriminatory views.”

SUE’S CREW Sue co-authored his breakthrough 2007 paper on microaggressions with (from left) then-students Christina Capodilupo Schwefel, Gina Torino, David Rivera, Aisha Holder and Kevin Nadal (not pictured here). He has continued to work closely and co-publish with them. (Photo: Bill Cardoni)

Sue says he was, and still is, influenced by the “marvelous militancy” of the ’60s and ’70s. But he’s also come to understand just how threatened whites can feel in conversations about racism.

“In workshops I conducted decades ago, white people felt that I was against them and blaming them, and they may not have been incorrect,” he says. “When they challenged me, I’d feel angry — I’d want to hurt them. But at some point, I changed — I realized, it’s white ethnocentrism, or white supremacy that’s the enemy, not white people — and that has lowered resistance to me.”

Ongoing Struggle

And yet, one has only to pick up a newspaper to find ongoing hostility to Sue’s ideas.

Since the end of Barack Obama’s presidency, the nation has been rocked by police shootings of young black men, the resurgence of the white supremacy movement and anti-Semitism, and the federal push to scale back immigration and deport the “undocumented.” Many observers speculate that Donald Trump’s appeal stems partly from his unrepentant deriding and baiting of minorities and women. In findings that National Public Radio termed a “warning to Democrats,” a recent NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll reported that 52 percent of Americans, including a majority of independents, are against the country becoming more politically correct and feel there are too many things people can’t say anymore.

The latter critique has been echoed by psychologists, free speech advocates and legal scholars.

NEWEST COLLEAGUES Sue’s current students have been co-authors on his recent publications on "microinterventions." From left: Narolyn Mendez, Cassandra Calle, Elizabeth Glaeser and Sarah Alsaidi; Not pictured: Michael Awad. (Photo: Bill Cardoni)

Writing in The Atlantic in 2015, Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at NYU, and Greg Lukianoff, President of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, warned of “a movement to scrub campuses clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense.” Its focus, they said, is on crying “microaggression” and demanding “trigger warnings” for potentially upsetting course content — including such staples as Chinua Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart (it describes racial violence) and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (it portrays misogyny, physical abuse and microaggressions).

Haidt and Lukianoff warned of a “vindictive protectiveness that violates the Socratic method of teaching students how to think rather than what to think,” and of handicapping young people in a world that “often demands intellectual engagement with people and ideas one might find uncongenial or wrong.”

Sue has other critics. The sociologists Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning have argued that microaggressions research has created “a culture of victimhood” in which people are so intolerant of even unintentional insults that they turn to courts and the media. Campbell and Manning see a regression from past “honor cultures,” in which slights were redressed through fighting, and “dignity cultures” where “insults might provoke offense” but no longer called into question the recipient’s reputation for bravery.

And the Emory College clinical psychologist Scott Lilienfeld argues that “there is scant real-world evidence that microaggression is a legitimate psychological concept.” In 2017, Lilienfeld called for a moratorium on microaggression lists and training programs: “No one has shown that [microaggressions] are interpreted negatively by all or even most minority groups. No one has demonstrated that they reflect implicit prejudice or aggression. And no one has shown that microaggressions exert an adverse impact on mental health.”

Microaggressions, Lilienfeld concluded, “necessarily lie in the eye of the beholder,” and “it is doubtful whether an action that is largely or exclusively subjective can legitimately be deemed ‘aggressive.’”

Sue has tacked his published responses to these critics to his office door. To some extent, they follow the standard “is not, is too” pattern of much academic debate, citing research showing that microaggressions do indeed increase recipients’ depression and affect emotional well-being; that in fact, because recipients endure them day in and day out, they inflict a kind of death by a thousand cuts, creating “a chronic state of racial battle fatigue” that siphons energy from studies or work.

But in refuting Lilienfeld’s “insufficient evidence” charge, Sue indicts western science itself.

Lilienfeld “fails to realize that there is more than one way to ask and answer questions about the human condition, that what constitutes evidence is often bathed in the values of the dominant society, and that scientific methods we employ often shortchange real-world contexts,” Sue says.

Citing the African proverb that “the true tale of the lion hunt will never be told as long as the hunter tells the story,” Sue asserts that microaggressions are indeed “about experiential reality,” and more pointedly, about “listening to the voices of those most oppressed, ignored and silenced.”

Such work “does not lend itself easily to objectivity and control of variables without separating people from the group, science from spirituality, thoughts from feelings, observer and observed, and man/woman from the universe.” Yet psychology has tried to style itself in the mode of the physical sciences, Sue says. To illustrate what such western empiricism misses, he recounts a parable told to him long ago by a Nigerian scholar:

A white teacher asks her class: “Suppose there are four blackbirds sitting on a tree branch. You take a slingshot and shoot one of them. How many are left?”

A Nigerian immigrant boy answers “zero,” prompting the teacher to suggest he study harder. But, Sue writes, “if the teacher had pursued the reasons behind the Nigerian student’s answer, she might have heard the following: “‘If you shoot one bird, the others will fly away’ — an answer based upon lived experience, a known relationship among birds, and an understanding of how the real (not hypothetical) world operates.”

People say, ‘Well, that’s your opinion.’ But social psychologists will tell you that the most disempowered groups have the most accurate understanding of what's going on

—Derald Wing Sue

That understanding, Sue argues, is the crux of the issue. Microaggressions may not meet some scientists’ criteria for being “real,” yet nonwhite faculty and students in Mississippi, Utah, Los Angeles and elsewhere report experiencing them regularly. In a two-week study of Asian Americans, nearly 80 percent reported experiencing a racial microaggression, and in an APA study, 75 percent of African Americans reported being subjected to daily discrimination.

And in the Personality and Social Psychology Journal, Keon West, a researcher at the University of London, has published a paper, summarizing three recent studies, with the self-explanatory title “Testing Hypersensitive Responses: Ethnic Minorities Are Not More Sensitive to MIcroaggressions, They Just Experience Them more Frequently.” West writes that “this current research takes an important step toward allaying” concerns raised by Lilienfeld and Haidt. In light of these findings, he writes, “our efforts seem better spent investigating ways of reducing these subtle, but harmful behaviors, than attempting to make ethnic minorities less sensitive to them.”

For Sue, these reports confirm a self-evident truth. “I like to ask: When you talk about racism, whose reality is the real reality? Social psychologists will tell you that the most disempowered groups have the most accurate understanding of what’s going on. The oppressed have to understand white institutions in order to survive, but white workers don’t have to understand what it’s like to be African American. So, it’s common sense — if you really want to understand racism, who are you going to ask, white people or people of color?”

Difficult Conversations

But do most white people want to understand racism?

No, says Sue, at least, not to the point of undertaking real self-scrutiny and behavioral change.

In a 2017 paper, “The Challenges of Becoming a White Ally,” Sue concurs with Beverly Daniel Tatum’s assertion that “active racists” are walking fast on a metaphorical conveyor belt in accordance with an ideology of white supremacy, and passive racists, though standing still, are on that same moving walkway.

HIGHEST HONORS In August, Rosie Phillips Davis, President of the American Psychological Association, presented Sue with the organization's Award for Outstanding Lifetime Contributions to Psychology. Past recipients include B.F. Skinner, Kenneth Clark, Judith Rodin, Albert Bandura, Beverly Daniel Tatum and Martin Seligman. (Photo: Gold Grid Studios)

Becoming a true “white ally,” Sue believes, requires developing authentic relations with people of color and an awareness of white privilege; taking action when microaggressions and other injustices occur; and, ultimately, fighting for change on a societal level.

White people who undertake such work are, literally, comfortable in their own skins. They acknowledge their inherent biases and limitations. And they are so rare that Sue, in a half-serious aside, wonders if they are born and not made. But in the next breath, he underscores the necessity of cultivating more of them.

“We fail to prepare our White brothers and sisters for the alternative roles they will need to play to be effective,” he writes. “We do not provide them with the strategies and skills needed for antiracist interventions; and we do not prepare them to face a hostile and invalidating society that pushes back hard.”

Will enough whites ever reach “ally-ship” to make a difference? Sue acknowledges that each conversion amounts to “a monumental task and lifelong journey.”

Still, he keeps at it, despite family and friends who ask why he doesn’t simply pass the torch and retire.

It’s common sense – if you really want to understand racism, who are you going to ask – white people or people of color?

—Derald Wing Sue

“I actually have minimal racial battle fatigue,” he says. “Early in my career, it was a struggle, and I’d get tired. But now I feel invigorated. The work I’m doing provides me with so much satisfaction and meaning and such a sense of liberation.”

Sue has come to accept that he can’t change everyone. “A third of people in workshops are receptive to the message, another third can be reached with a lot of work, and the rest are so difficult to reach that if you focus on them, you hinder everyone else. So I target the middle.” Meanwhile, it’s clear that people of color appreciate his efforts. In October, not long after the APA honored him, he received another lifetime award — this one emblazoned with the logos of psychological associations representing the country’s major ethnic and cultural groups. “I think,” he said, his voice catching, “that this one is the most meaningful of all.”

— Joe Levine

We want to hear your thoughts on this piece. Please write to us at newsyoucanuse@tc.columbia.edu.