“Education data” is not a phrase that makes many hearts beat faster – but Alex Bowers believes it could if the rest of us saw what he sees.

Sixteen years ago, as a cell biologist for a pharmaceutical company, Bowers was spending his days sifting through the just-released Human Genome Project, looking at billions of base pairings of nucleotides to identify genetic targets for new cancer drugs. He quit to teach science at a local community college, earned an education degree and is now Associate Professor of Education Leadership at Teachers College. But he brought one extremely transferrable skill with him: an ability to create “visualizations,” or graphic representations that make overlooked patterns leap out from masses of data. For his dissertation at Michigan State University’s Graduate School of Education, for example, he used a technique called cluster analysis to predict which elementary school students in a local district were at risk for failing to graduate from high school.

Alex Bowers (Photo: Morgan Gilbard)

Today, Bowers is focused on converting teachers to believers in the power of data science. It’s a daunting challenge in an era when, for many educators, “data” has become synonymous with standardized testing, narrow definitions of intelligence and achievement, and punitive evaluations. Others complain that the reports they receive on school and district “data dashboards” are incomprehensible, or that by the time they receive them, their students have moved on to the next grade.

To all of them, Bowers is selling a very different vision.

“Using evidence in schools is about building relationships,” he says. “It’s not about ‘doing data’ to teachers, but instead about creating honesty, trust and capacity.”

Three years ago, backed by a three-phase $500,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Bowers entered into a partnership with New York’s Nassau County Board of Cooperative Educational Services (Nassau BOCES), which provides shared educational programs and services (including data warehousing) to the county’s 56 public school districts.

Using evidence in schools is about building relationships. It’s not about ‘doing data’ to teachers, but instead about creating honesty, trust and capacity.

—Alex Bowers

Phase I of the grant focused on educators’ perceptions of data and data use. Bowers surveyed teachers and administrators in all 56 districts on whether and how teachers were using data. The teachers and administrators were in near-unanimous agreement that the teachers do rely on pop quizzes and other student data that they themselves collect. But nearly half of the teachers reported that they didn’t use data about their students’ performance on state mathematics and reading tests, even as 86 percent of the district’s administrators reported that their teachers were major data users. That was a key finding, because the survey also revealed that teachers who do use that data are those who feel supported by the school administration.

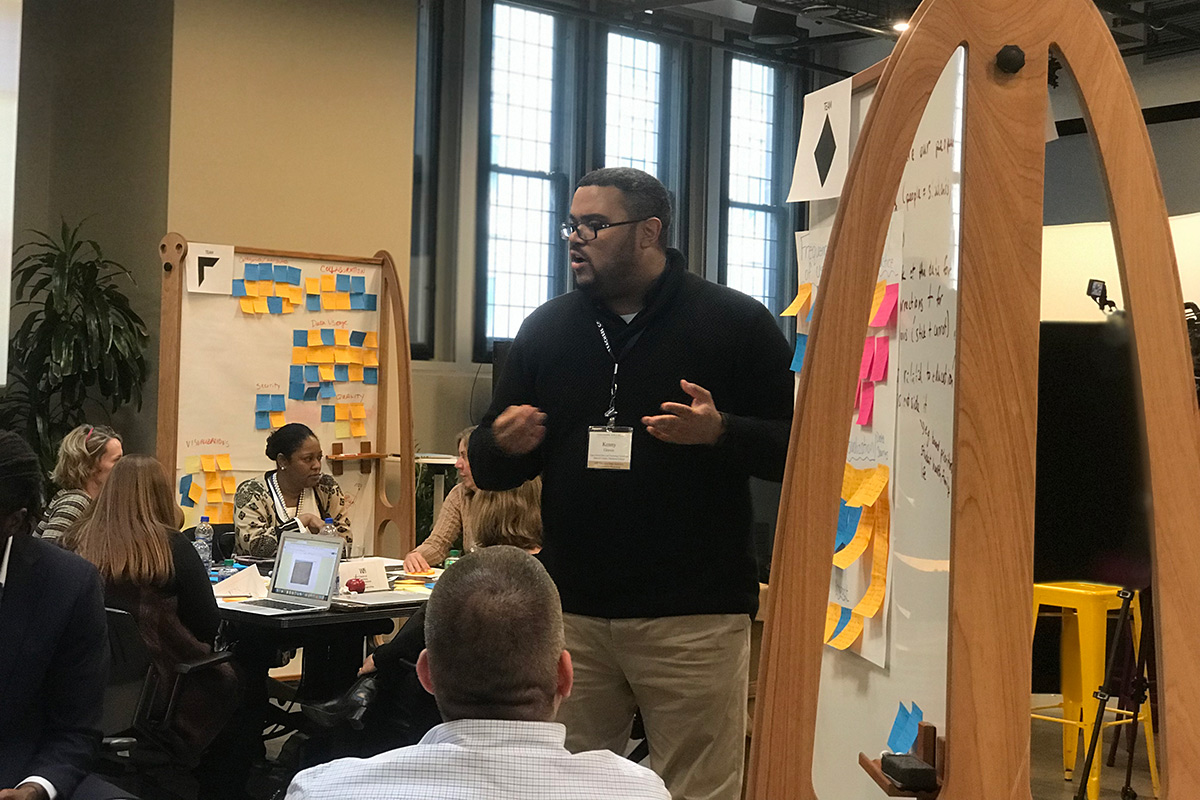

PARTNER ON THE FRONTLINES The TC conference on education data use was co-facilitated by Kenneth Graves (Ph.D. ’19), who is Upper School (9-12) Ethics & Technology Coordinator at New York City’s Ethical Culture Fieldston School. Graves, whose dissertation advisor was Alex Bowers, is also an adjunct professor at TC’s Klingenstein Center for Independent School Leadership and at Boston College. (Photo: Alex Bowers)

The second phase of the grant focused on how the educators actually use data. Bowers and his team examined a year’s worth of log files and data clickstreams for all Nassau County educators who use the Nassau BOCES Instructional Data Warehouse – the first such study ever conducted.

“State and district-level data dashboards were originally built for policymaking, under NCLB [the federal No Child Left Behind Act] so we wondered, to what extend were educators using those systems?” Bowers says. “And companies keep building large data dashboards for schools without talking to teachers, and then everyone wonders why no one uses them.”

Companies keep building large data dashboards for schools without talking to teachers, and then everyone wonders why no one uses them.

—Alex Bowers

Phase III of the grant took place at Teachers College in early December, when Bowers held a conference that drew 80 attendees -- primarily educators from Nassau County, but also top data scientists from around the country. Representatives from major data companies, including IBM, were also there.

Keynote speaker Richard Halverson, coauthor of Rethinking Education in the Age of Technology: The Digital Revolution and Schooling in American Education (Teachers College Press 2018), forecast a new era in which educators and students take control of data (rather than merely generating it for use by higher-ups) to personalize learning and improve their own skills. Halverson is Professor and the Associate Dean for Innovation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Education.

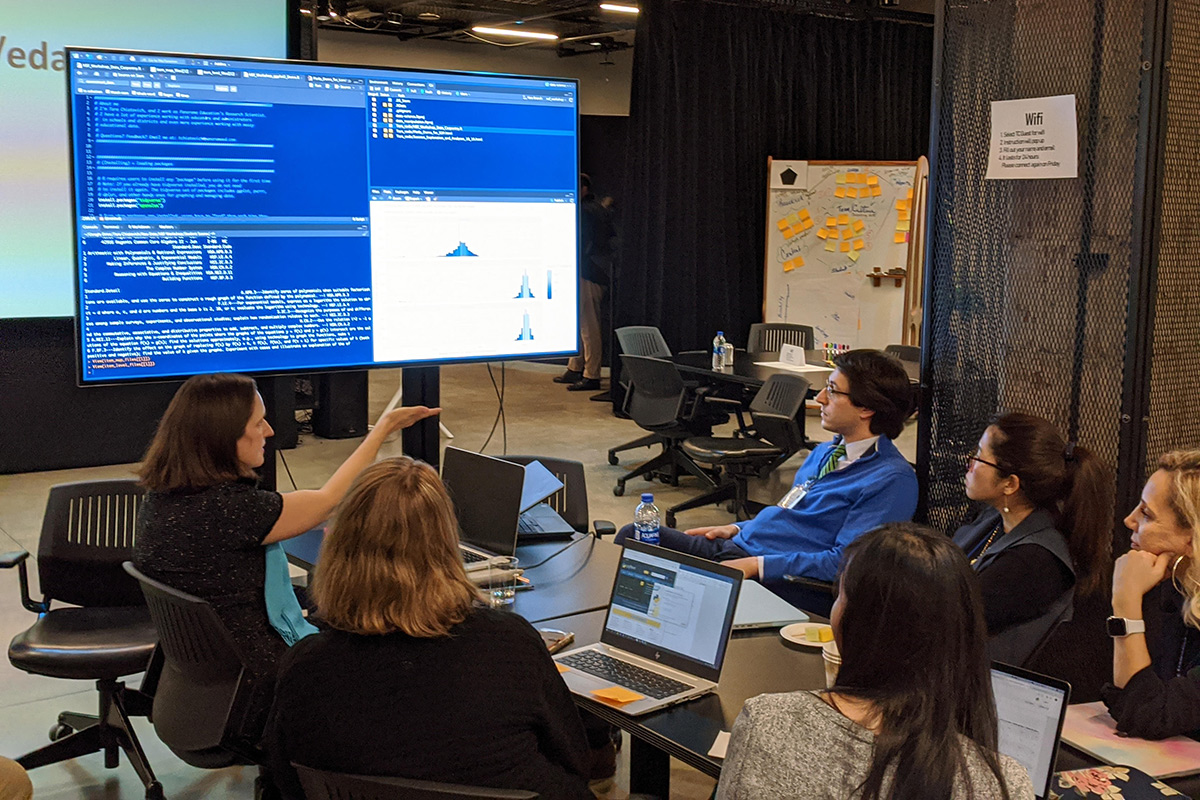

Then, over the course of two days in TC’s Smith Learning Theater, 11 sprint-data teams comprised of educators and data scientists created visualizations of data that the educators said they wanted and would use. The scientists began building these new tools on the spot via open-source software for use nationwide. The conference’s second day included a morning “expo” in the Learning Theater in which the participants walked around to take a look at all the different projects in the works. Never one to pass up a new data-gathering opportunity, Bowers gave each person an electronic tracking chip so that he could subsequently graph which projects attracted the most traffic.

(Photo: Alex Bowers)

“I actually wrote this part of the grant around the Learning Theater,” he says. “I really wanted to take advantage of the awesomeness of TC’s facilities.”

During 2020, Bowers will release an e-book from the meeting with coding for the new tools. His hope is that the tools will find widespread uptake through Cognos, a backend data system used by one-fifth of all school districts in the United States, including those supported by Nassau BOCES. Meanwhile, it’s clear that his Nassau County partners are pleased.

I actually wrote this part of the grant around the Learning Theater. I really wanted to take advantage of the awesomeness of TC’s facilities.

—Alex Bowers

“This was fantastic, because our ability to provide our teachers with useful data really depends on the input they give us,” said Meador Pratt, Supervisor of the Nassau BOCES Instructional Data Warehouse. “And on top of that, we got input from data scientists, whom we rarely have the opportunity to talk to.”

Currently data use within district schools is “hit or miss,” Pratt said, but contrary to what one might expect, the big users aren’t all younger teachers.

“Our number one biggest user in the whole county is Fred Cohen, and he’s 75,” he said, pointing to a man typing away on his laptop. “He’s a retired deputy superintendent and former English teacher. He had concerns about the quality of the data that we were providing to teachers – that it wasn’t information that teachers could easily link to action in the classroom – so we said, come work for us. So our biggest user is probably the oldest guy in the room.”

Bowers is steadily adding to the ranks of converts by teaching a non-credit course on educational data use through TC’s Continuing Professional Studies arm. He’s also designing a new icon for schools’ data dashboards that will enable teachers, administrators and others to jump directly to whatever information is currently trending highest among all who are working in similar roles.

“It will be similar to the way Netflix recommends movies for you, based on data about what you’ve already been watching,” he says. “The key is help you find the data you want.”