Career and technical education (CTE) has long been dismissed by many as non-rigorous programming for students who are not headed to college. Now CTE is making a comeback in American public high schools — but questions remain about its impact on educational equity.

Now a team from Teachers College’s Departments of Education Policy & Social Analysis (EPSA) and Social Studies & Education, consisting of then-doctoral students Elisabeth H. Kim (Ph.D. ’20) and Clare Buckley Flack (Ph.D. ’20), current doctoral student Katharine Parham, and Priscilla Wohlstetter, Distinguished Research Professor in EPSA, have published what Wohlstetter calls “the first systematic literature review in the field of CTE with an explicit focus on equity.” [Read a story about Kim, Flack and Parham.]

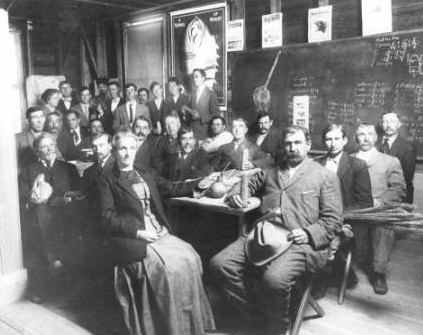

POOR TRACK RECORD The Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 provided states with funding for vocational education in agricultural and industrial trades and in home economics. But vocational education came under fire for tracking low-income students into low-paying jobs. (Photo: FFA.org)

Using a novel framework that they designed, the TC team reviewed relevant studies published between 1998 and 2019 to determine how well secondary CTE programs are working, including for low-income students, those who are Black, Indigenous or of color (BIPOC), English language learners, LGBTQ students and those with documented disabilities.

“In an already under-studied field, research has not kept pace with policy interest or program expansion, particularly in the area of equity,” Kim, Flack, Parham and Wohlstetter write in their paper, “Equity in Secondary Career and Technical Education in the United States: A Theoretical Framework and Systematic Literature Review,” published recently in Review of Educational Research, the American Educational Research Association’s number one-rated journal. “[G]iven CTEs’ roots in vocational education, an academic pathway with a ‘pernicious’ history of limiting the attainment and achievement of marginalized populations, it is important to ask how CTE affects educational equity.”

[G]iven CTEs’ roots in vocational education, an academic pathway with a ‘pernicious’ history of limiting the attainment and achievement of marginalized populations, it is important to ask how CTE affects educational equity.

—from a study of career and technical education (CTE), published by a Teachers College team in Review of Educational Research

More simply, they frame their questions about CTE programs by quoting the sociology researcher Gerhard Lenski: “Who gets what and why?”

As the paper describes, vocational training in the United States, first funded by the federal government in 1917, was adapted from the German industrial education system. It was designed for students who would work in manufacturing, farming, home economics or other trades that did not require a college education.

This stratified tracking system remained basically in place until the 1980s, when an increasingly global and sophisticated labor market began demanding higher-skilled, better-educated employees. The federal government responded by shifting its focus from job training programs to career training and education programs, requiring that these programs improve their academic rigor. The government also introduced “broad curriculum clusters… in place of specialized training for particular jobs.” These measures aligned CTE with post-secondary education and made it “an integral part of the U.S. education system.”

CTE RESEARCH TEAM From left, Elisabeth Kim (Ph.D. ’20), Clare Flack (Ph.D. ’20), current TC doctoral student Katharine Parham and Priscilla Wohlstetter, Distinguished Research Professor. (Photos: TC Archives)

More recently, both the No Child Left Behind Act, passed in 2001, and its successor, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2016, have required school systems to report on how different subgroups of students are performing on standardized tests and the rates at which they are graduating. The so-called “Perkins V” bill, passed in 2018, imposes similar accountability measures for CTEs that aim to identify and improve underperforming student subgroups.

In reviewing literature in the field, the TC team asked: Do secondary CTE programs in the United States meet minimum standards of educational adequacy, such as enabling graduates to actively engage in citizenship, and to “compete effectively in the modern economy”?

But federal law has still “lacked explicit attention to equity” for CTE programs. With that gap in mind, the TC team evaluated 123 published papers on CTE, asking:

- Do secondary CTE programs in the United States meet minimum standards of educational adequacy, such as enabling graduates to actively engage in citizenship, and to “compete effectively in the modern economy”?

- Do students from historically marginalized groups receive equal treatment with respect to the quality and quantity of CTE opportunities and experiences, both within and across schools?

- What do observed differences in academic and social and emotional outcomes across student groups suggest about equality of educational opportunity in secondary CTE?

They learned that:

- CTE programs that integrate academic and CTE content in rigorous, authentic ways and include small-group instruction, opportunities for real-world connections and project-based learning show promise for equity.” But “high-quality teachers” and BIPOC CTE teachers are scarce.

- Barriers to access are particularly high for girls, students with disabilities and BIPOC students. High school girls and students with disabilities are less likely to participate in CTE, particularly in careers in which women were historically underrepresented, “due in large part to discrimination and barriers to access.”

- CTE programs with well-defined career pathways, with aligned core academics, and in which students are placed in smaller learning communities such as career academies have the most positive educational outcomes. But disparities exist in enrollment in, and completion of, these high-quality CTE programs.

The researchers also found little research that compares outcomes for different groups of students. They urge more research on school culture and community-building within CTE programs and within schools. They also highlight a need for more attention to equity in data collection enterprises at the state and federal level.

Ultimately, the article concludes, CTE programs should be held to the same standards of equity in access and rigor as any American high school curriculum. “The OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] and others have shown that centering equity in the pursuit of educational improvement is necessary,” they write, adding that, according to the OECD, “‘there can be no effectiveness without equity.’ A system that does not work for everyone is not a system that works. Practitioners, researchers, and policymakers must remember this as we move forward in a rapidly transforming landscape.”