The success of the interventions in an early career project that improved learning by students in rural India sparked a new idea for TC’s Alex Eble.

“What if we found a place where there was a huge, unmet need for teaching people very basic numeracy and literacy skills,” said Eble, an Assistant Professor of Economics & Education. “And what if our work there had the transformative potential to move the needle further than we ever thought possible.”

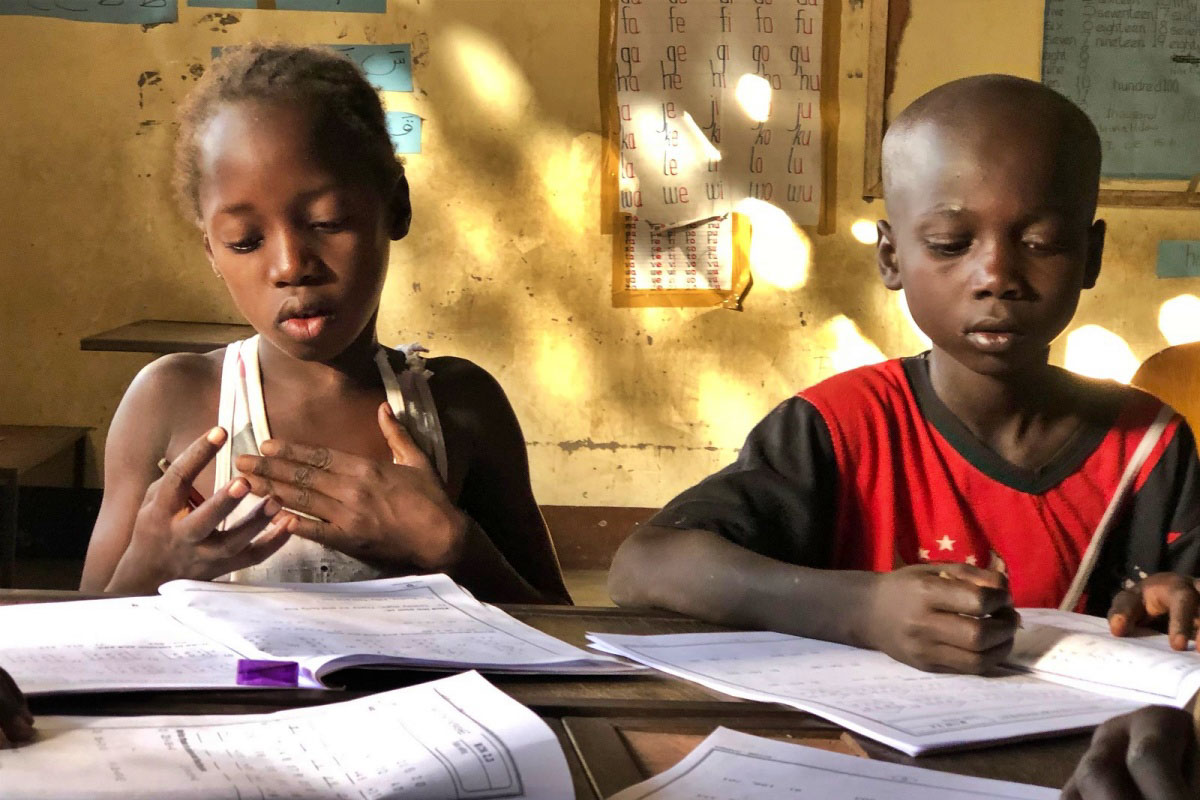

The question pointed Eble toward Gambia, an impoverished West African republic where the vast majority of third grade children are unable to read and where fewer than 60 percent reach the Gambian equivalent of high school.

Alex Eble, Assistant Professor of Economics and Education. (Photo: TC Archives)

Funding from private donors in the UK created an opportunity for Eble and a team to develop after-school programs that empowered “community educators” to bolster child learning through an intervention which brought together multiple prongs – such as teacher professional development, learning materials and data-driven analytic tools – known to raise learning in isolation.

With the support of the Gambian government, the team introduced this “well-oiled machine” to children between the ages of six and eight in a randomized evaluation, covering 169 villages spread across the central region of a country where electricity, technology and printed publications are often in short supply.

"Then we let it rip for three years," said Eble.

The community educators over that period delivered after-school instruction from scripted lesson plans developed by educators and pedagogical experts.

Eble got an inkling of what lay ahead while monitoring student progress. The young people enrolled in the after school programs, he discovered, could readily solve the same fundamental math problems that stymied control groups in non-participatory villages.

“The kids who didn't get interventions looked at me like I came from Mars,” Eble recalled.

The anecdotal evidence was born out when researchers evaluated cumulative test data.

Alex Eble (center) pictured, meeting with local experts in The Gambia. (Photo courtesy of Eble)

Gambian children in villages with the after-school programs scored 46 percentage points higher on combined literacy and numeracy measurements than counterparts in non-participatory villages. (A smaller project yielded similar outcomes in a second West African nation, Guinea Bissau.)

“Our results demonstrate that...aggressive interventions can yield far greater learning gains than previously shown,” Eble and co-authors wrote in a paper published in January by the Journal of Development Economics.

“The hallmark of a good research question is when what you find is interesting, no matter the outcome,” said Eble. “But when the research strikes on something both a scientist and a policymaker would want to know, we need to get on top of it.”

Which was exactly Eble's intent as he and his team crunched the numbers and began to author their findings in 2019. The project provided an unequivocal answer to his question about the difference intentional interventions can make in the lives of young people in underserved nations.

The plan was to return in 2020 when students in the study groups entered fifth grade – a plan Covid wound up “blowing out of the water.” Eble views the subsequent health precautions and travel bans as a temporary setback.

The question now isn't if the work will continue. But when.

“It was a big loss,” Eble says of the timely opportunity stolen by the pandemic. “But our work is transformational. Come hell or high water, I'm going back to Gambia.”