By Jen Lee, Media Producer

When Professor Ansley Erickson asked the Digital Futures Institute to collaborate with her and the New York City Civil Rights History Project (NYCCRHP) on a set of videos that would convey the power of engaging with primary sources, we developed an approach meant to bring viewers as close as possible to that experience while ensuring those being filmed were as comfortable as possible.

Project background

Often when we think about learning history, we imagine learning from a textbook. That’s what it looked like for many of us. But how much more would the events of the past come to life if we went directly to primary sources, to examine them for ourselves and draw our own conclusions?

This is what the New York Civil Rights History Project (NYCCRHP) makes available to us. Their website has located and licensed scores of primary sources, collecting them into a searchable online library.

When the Digital Futures Institute (DFI) media team partnered with Teachers College Professor Ansley Erickson in her work with the NYCCRHP, the project had an additional aim: to create videos that modeled what a “close reading” of these sources might look like. The idea was to film people from various backgrounds and positions interacting with a primary source and bring viewers into the experience.

A media producer’s perspective

This was a video production goal that needed some planning and creative thinking. One thing I’ve often contended with during my background as a documentary filmmaker is the way we often ask the people being featured to “just act natural”, while surrounded by strangers, in the beam of bright lights, and with a camera lens pointing directly at them. It would be a challenging task for many of us.

When designing the approach for these videos, I wanted to eliminate all the variables I could that might cause self-consciousness or distraction. Our team often films in an interview format, with the person on camera directing their words to an off-camera interviewer. But even this brings an element of performance into the on-camera presentation. The person speaking will likely try and project their voice at a certain volume to be heard by the person sitting a few feet away, for instance.

But in line with the aims of this project, I wanted to capture something more intimate. I wanted to feel, as a viewer, that I wasn’t just watching a person encounter a primary source–I wanted to feel as though I was inside the experience they were having. Even if I was hearing their voice, I wanted to feel as though I was inside their thoughts as they were having them.

Videography techniques that connect the speaker and viewer

I proposed an unusual approach. We could film the on-camera person (or, “the subject”) through a window, from the studio next door. That way our crew and cameras would be out of sight. Inside the room where the on-camera person was sitting were accessibility staff when needed, and a member or two from the project itself, to provide thought prompts when necessary. We asked our subjects to speak as if only to themselves. We put a microphone on their collar or lapel to capture the quiet quality of their voices, as their heads were often tilted downward toward the primary source in front of them.

Kadiatou Tubman, wearing a lapel mic, reflects on digital primary source materials

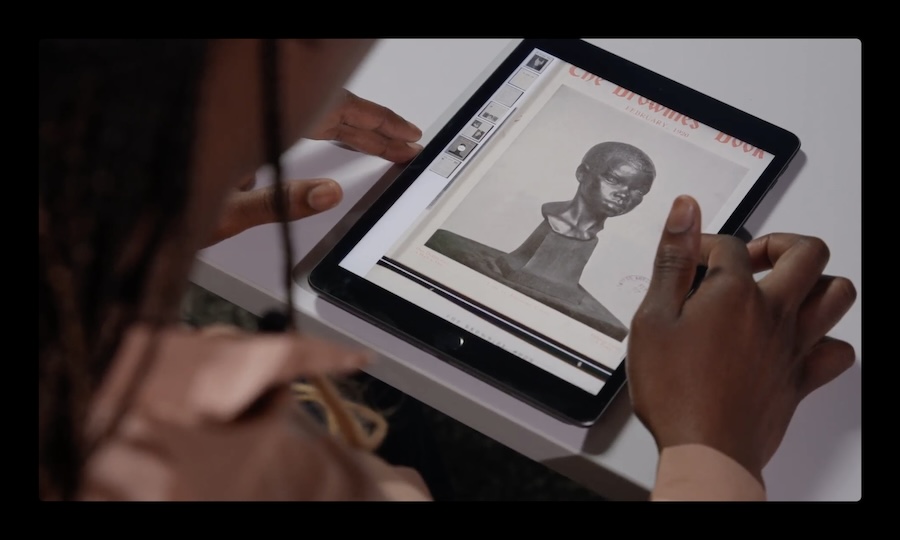

To create the feeling of being inside their thoughts and experience, we also filmed footage of them silently reading or interacting with the primary source when it was first presented to them, before they started speaking. The camera captured their expressions and silent reactions, along with passages they noted or highlighted. Later, if they mentioned those moments in their reflections, we cut in that footage on top of their voice, which gives viewers that feeling of being inside thoughts and an experience.

A zoom-in on the primary source material, from Kadiatou Tubman's perspective, to provide more access to their point of view

Conclusion: A video series & history comes to life

The final result was a series of videos that are quietly dramatic. A diverse collection of people whose feelings and thoughts were captured with little interference from production crew or equipment. Encounters that are deeply personal, resonant, and powerful.

It was exciting to bring these primary sources to the foreground and to watch people engage with them, and to be moved by them. We hope they will help viewers get a sense of how they might explore the primary sources on the NYCCRHP site and have close reading experiences of their own.

This project is in partnership with the NYC Civil Rights History Project through DFI’s Transmediation Fellowship.