"/imagine [PROMPT]": A Chat with @MidJourneyBot, or 10 Provocations for the Future of Media Literacy

- Ioana Literat

Associate Professor of Communication, Media and Learning Technologies Design

Introduction

hey @MidJourneyBot, how are you?

let’s do something a little different today…

i’m gonna tell you all about media literacy and misinformation, and share 10 provocations for the field going forward

and you're gonna help me imagine these visually, ok?

i mean, no offense, but bots like you, artificial intelligence, yada yada… you play a big role in both the present and the future of media literacy and misinformation, so might as well humor me in having this conversation, right?

right. then let's get started.

#1 /imagine: what would it look like to stop treating media literacy like a panacea?

media literacy is often touted as THE solution to our current crisis (crises?), especially when it comes to youth (although they might not be the demographic that needs it most -- but that’s another story for another time…)

and of course it does help in many ways, especially “as a flexible response for both teachers and students following current events, as a method of linking critical thinking and behavior change for youth, and as a foundation for accurately digesting partisan content” (Bulger & Davison, 2018)

but this media literacy “solutionism” is dangerous (Buckingham, 2017), in that it presents “narrow versions of media literacy and critical thinking [as] the solution to major socio-cultural issues.” as boyd (2018) emphasizes, media literacy is “not a panacea for what ails our democracy or news environment.”

and oh man, do our problems run deeeeeep.

“current divisions in liberal democracies are not just about policy priorities or sectoral interests; they are divisions about values, moral universes, and epistemological frameworks, i.e. about the ways in which we understand the world” (Gerodimos, 2022, p. 104)

we cannot fact-check our way out of these problems -- and, as we’ll talk about later, these deep moral and epistemological divisions also problematize the practical implementation of media literacy.

so all this is to say: we need to be real about the kinds of challenges media literacy can and cannot tackle.

/imagine PROMPT: what would it look like to stop treating media literacy like a panacea?

#2 /imagine: what would it look like to move beyond individual responsibility and hold the big players accountable?

and part of why media literacy is not and can never be a panacea is because the current framing of media literacy puts the onus squarely on the individual

if you look at the definitions of media literacy, it's all about personal responsibility... "the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication” (NAMLE, n.d.)... "the ability of a citizen to access, analyze, and produce information for specific outcomes” (Aufderheide, 1993)

“the onus is on the public to interpret what they see. To self-investigate… It’s up to each of us as individuals to decide for ourselves whether or not what we’re getting is true” (boyd, 2018, n.p.)

because [gestures wildly around me].... neoliberalism !

but the problem is that this focus on personal responsibility can not only give people a false sense of confidence in their skills, but it also takes the pressure off media creators, social media platforms, or regulators, who should also be doing their part (Bulger & Davison, 2018)

we need to more vocally, urgently, effectively push for institutional and corporate accountability when it comes to misinformation

so, @MidJourneyBot…

/imagine: what would it look like to move beyond individual responsibility and hold the big players accountable?

#3 /imagine: what would it look like to -- earnestly, openly, bravely -- interrogate the relationship between media literacy and epistemology today?

here’s where it gets really tricky (and kinda sad)

a long-held assumption behind media literacy education is that “it works by helping students understand certain truths about mediated communication, and the world in general” (Friesem & Friesem, 2021, p. 125)

but this implies a certain stability of truth, of facts, of “evidence.” it is NOT where we are today.

(see, this is where the sad part comes in:) we are now, unfortunately, in the era of “alternative facts.” where the meaning of evidence is contested. where “truth” is a source of division rather than something held in common.

the field of media literacy needs to contend with this new reality. asking students to support their answers with evidence is naive in a world where “evidence” is interpreted -- and used and, sometimes, weaponized -- so differently.

“I’m not convinced that we know how to educate people who do not share our epistemological frame,” boyd (2018) wrote. and i agree. i’m not convinced either.

this might be uncomfortable, but a self-reckoning is in order -- and, as part of this self-reckoning, we need to ask the big, tough questions about the relationship between media literacy and truth itself.

/imagine: what would it look like to -- earnestly, openly, bravely -- interrogate the relationship between media literacy and epistemology today?

#4 /imagine: what would it look like to stop pretending that media literacy is apolitical?

let’s just put it out there: as a practice, and as a set of values and skills, media literacy is couched in “decidedly liberal narratives” (boyd, 2018)

explicitly or -- most often -- implicity, “we imply that to be media literate one needs to pass an ideological litmus test” (Rogow, 2016, n.p.)

Rogow (2016) argues that the way to avoid this is to focus on skills and dispositions instead of ideology: “teach students to identify the sources of their ideas, provide evidence and logical argument to back up their interpretations, and respect differing interpretations as long as they are reasonable and evidence-based” (n.p.)

this sounds good in theory, sure, but increasingly idealistic in practice. (not to mention that, once again, it places faith in narrow, individual-level solutions…). plus, what happens when “differing interpretations” are NOT “reasonable and evidence-based”?

looking ahead, we will have to contend with the liberal slant of media literacy, as a practice and as a field. we will have to make a choice between embracing it and doubling down on the social justice values that have defined media literacy from the get-go (more on that below), or, conversely, downplaying it in an effort to make media literacy education more palatable?

i think you know where i stand.

but i've never been one to prioritize palatability.

/imagine: what would it look like to stop pretending that media literacy is apolitical?

#5 /imagine: what would it look like to broaden the media literacy discourse beyond fake news and (re)center social justice?

you know what really bugs me these days? the fact that media literacy has become associated almost exclusively with fake news. or rather, that “fake news” has eclipsed the whole conversation about media literacy.

yes, yes, i know there are upsides too. i realize this is an opportunity to get stakeholders excited and aligned. i'm grateful for the extra funding and attention that has been poured into our (historically underfunded and underlooked) field.

but media literacy is so much more than just fake news.

the history of the field is intimately tied to questions of social justice, power, identity and representation (Kellner & Share, 2007). these continue to be vital, perhaps now more than ever.

we shouldn’t forget about the “critical” in “critical media literacy”: “critical media literacy asks us to not only access, analyze, evaluate and create, but to critically interrogate the power media has in shaping our lives, values, and experiences, while opening up the possibility to critically create new narratives, representations, and structures” (Critical Media Project, n.d.).

indeed, you cannot teach any kind of literacy, including media literacy, without teaching about values of social justice, and the way power and oppression work in the world (Bali, 2018)

so how about we bring that all back please?

/imagine: what would it look like to broaden the media literacy discourse beyond fake news and (re)center social justice?

#6 /imagine: what would it look like to foreground voice and action, while grappling with the complexities of youth online participation?

and speaking of the need to shift focus, here’s another issue… much of media literacy research and practice still privileges processes of interpretation

remember the NAMLE definition we talked about earlier? media literacy as "the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication” (NAMLE, n.d.)?... well, it’s time to really drill down on those last two verbs: create and act. the fact that they always appear last in various definitions of media literacy should not signal that they’re less significant (though in practice it kinda does)

as Mihailidis (2018) put it so eloquently (as he always does), we need to urgently reimagine media literacy interventions as “intentionally civic.” AMEN. and to do so, we must “develop curricula for addressing action in addition to interpretation” (Bulger & Davison, 2018, p. 20)

in the age of social media, this also means “teach[ing] for online public discourse” (Middaugh, 2019, p. 27). after all, as Allen & Light (2015) remind us, a civic voice must be honed and learned.

but here’s the tough part: (most) young people are already really skilled at exercising their civic voice online and -- we might not want to hear this -- it’s not always in service of “good” engagement or “good” citizenship.

if we’re going to focus on action and reimagine media literacy as intentionally civic, we need to ask ourselves: what kind of engagement should be valued, and what is corrosive to democracy – even when it’s done by youth? how can we help youth hone voices that are prosocial and prodemocratic?

/imagine: what would it look like to foreground voice and action, while grappling with the complexities of youth online participation?

#7 /imagine: what would it look like to learn from the COVID crisis and immunize against misinformation?

media literacy education has been applied and studied widely in health-related contexts (see, e.g. Vahedi, Sibalis, & Sutherland, 2018, for a youth-focused overview); that has always been a fertile ground for media literacy research and practice.

but the COVID pandemic was something else altogether. It was also, in the (in)famous words of the WHO, an “infodemic” (which btw, in terms of my pure hate for the term, is right up there with “digital natives.” seriously, stop calling youth “digital natives.” just. stop.)

the pandemic laid bare how vulnerable we are to mis- and disinformation, while foregrounding important distinctions between them

it showed how even a public health topic can be politicized in a divided, polarized, hyperpartisan climate -- and, in many ways, it made media literacy feel real. more than an abstract concept, media literacy was now about bodies, about health, about life and death -- nothing more real than that.

tt also “turned many myths about digital media on their head,” challenging protectionist arguments based on the concept of “screen time” (Jenkins, 2020) and reinforcing the significance of media literacy in our daily lives

but now that we’re in Year 3 of the pandemic, how do we build on what we’ve learned about media literacy during COVID? How might we think of immunizing against misinformation, just like we immunize against the virus? And how do we ensure that the rollout of this media literacy “vaccine” is equitable and unmoored in politics -- two fronts on which the COVID vaccine rollout failed terribly?

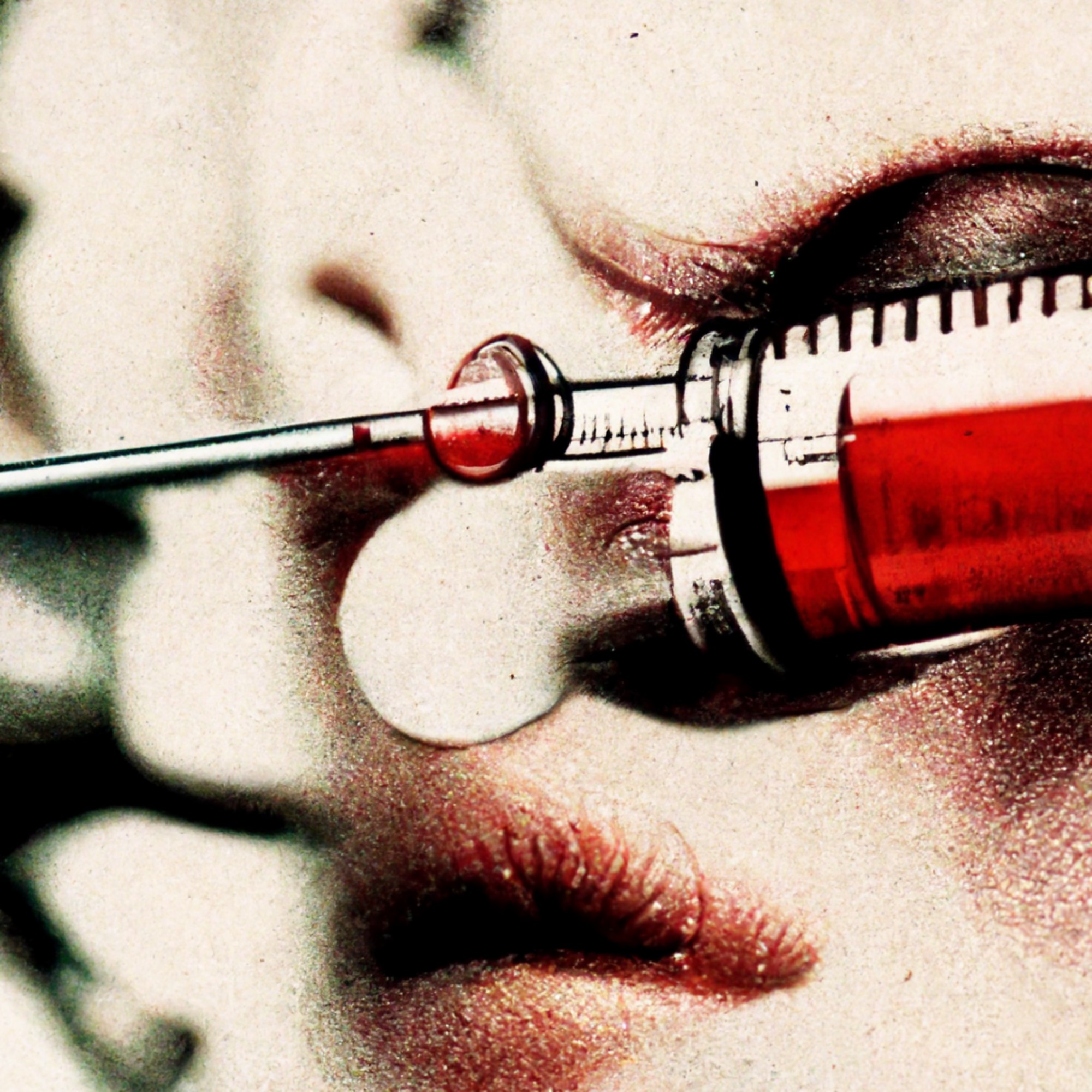

/imagine: what would it look like to learn from the COVID crisis and immunize against misinformation?

#8 /imagine: what would it look like to talk *to* each other rather than *at* each other, and move toward interdisciplinary harmony?

one thing you should know about the media literacy field, dear @MidJourneyBot, is that we’re an unruly bunch

call it conceptual cacophony… or the more euphemistic “theoretical disorganization” (Wuyckens et al., 2022), if you will

we have different terms with boundaries unclear and overlapping: media literacy, information literacy, news literacy, and digital literacy (Jones-Jang et al., 2021)... and the list is constantly growing.

“much work remains to be done to map the specificities of these concepts, their boundaries and the ways in which they overlap” (Wuyckens et al., 2022, p. 177)

this is not only important in a theoretical sense, but in a very practical sense too, as the multiplicity and blurriness of concepts affects how media literacy is operationalized and how “effectiveness” is assessed

Sure, this “theoretical disorganization” can be explained in part by the diversity of disciplinary and theoretical backgrounds that characterizes the field… but as media literacy pioneer Renne Hobbs (2018) put it, we must ask ourselves whether this diversity is ultimately “a source of strength or weakness”

maybe, just maaaaybe, the current attention to “fake news” is an opportunity to create disciplinary bridges, paving the way for more “cross-disciplinary collaboration and therefore greater coherence within the field” (Bulger & Davison, 2018)...

/imagine: what would it look like to talk *to* each other rather than *at* each other, and move toward interdisciplinary harmony?

#9 /imagine: what would it look like to fearlessly (self-)interrogate and, yes, criticize media literacy?

you probably noticed i’ve been bringing up boyd’s infamous critique of media literacy a lot in this chat. well, it’s because it really resonated with me.

but what i haven’t really emphasized enough is what a big deal it was in the field. some called it a paradigm shift (Friesem & Friesem, 2021). others called it d-r-a-m-a. “media literacy Twitter” in early 2017 was on fire. everyone had their popcorn out.

but there’s a bigger point here. the backlash to boyd’s argument also felt like nobody could or should criticize media literacy. at the risk of ruffling some feathers, i say: the reaction to boyd’s critique reinforced her point about media literacy being seen as a “sacred cow”

as Mihailidis has argued, we need to keep interrogating what media literacy “is doing at various points, both in education and in public life (quoted in Hobbs, 2017). while not without its faults, boyd’s critique was incredibly necessary and bold, pushing us to think deeply about media literacy’s core assumptions, context and implications.

to put it bluntly, we need to stop idealizing media literacy and ask the hard questions -- questions about feasibility and efficacy, but also values, epistemology, politics…

asking such questions doesn’t indicate a lack of trust in the potential of media literacy, nor a lack of respect for those who have passionately paved the way

and we shouldn’t shy away from asking these questions just because we don’t have clear answers. constructive criticism is great and all, but destabilizing a paradigm is pretty badass if you ask me.

so…

/imagine: what would it look like to fearlessly (self-)interrogate and, yes, criticize media literacy?

#10 /imagine: what would it look like to find that perfect mix of pragmatism and optimism that allows us to move forward?

well, we’ve reached the end of our chat, dear @MidJourneyBot, so i guess it’s time to get personal and end on a wistful note…

here’s something i’ve been struggling with: when it comes to the future of media literacy, given the seemingly insurmountable (sociopolitical, epistemological, technological…) challenges we’re facing, *how do we not fall into an abyss of desperation?*

how does one walk the line between hopefulness and resignation, proactivity and pessimism? I’m not sure i’ve figured this out yet.

when i read commentaries by the luminaries of media literacy -- Renee Hobbs (2018), Faith Rogow (2016), Paul Mihailidis (2018) -- i’m struck by the undeniable current of optimism that runs through their words, and their work.

Rogow (2016), for instance, writes: “In my vision of a media-literate nation there isn’t political uniformity… But everyone will be able to trust that opponents are well-informed and understand what’s at stake. Disagreements won’t dissolve into demonizing. And when elections are over, we will find common ground and work together to make the nation a better place. We’re not there right now, but we can get there.” i want to ask her if she still believes this today, in 2022. maybe i should. maybe i will.

here’s another question: do we need optimism to keep going? is idealism a feature, not a bug, of media literacy work?

“being optimistic about the future of education — and the future of our society and our democracy– is a choice we make that enables us to press on against great odds,” Hobbs (2018) wrote. and I made a similar point, writing on research as a form of civic imagination: “optimism is fuel to my research and inextricable from it. I need to be hopeful, because it is hope that drives me” (Literat, 2021, p. 110).

so i leave you with this final prompt:

/imagine: what would it look like to find that perfect mix of pragmatism and optimism that allows us to move forward?

- Allen, D., & Light, J. S. (Eds.). (2015). From voice to influence: Understanding citizenship in a digital age. University of Chicago Press.

- Aufderheide, P. (1993). Media literacy: A report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. Aspen, CO: Aspen Institute.

- Bali, M. (2018, March 18). Too critical, not critical enough [Blog post]. Reflecting Allowed. Retrieved from https://blog.mahabali.me/social-media/too-critical-not-critical-enough/

- boyd, d. (2018, March 9). You think you want media literacy... do you? Retrieved from https://points. datasociety.net/you-think-you-want-media-literacy-do-you-7cad6af18ec2

- Buckingham, D. (2017). Fake news: Is media literacy the answer? Retrieved from https://davidbuckingham.net/2017/01/12/fake-news-is-media-literacy-the-answer/

- Bulger, M., & Davison, P. (2018). The promises, challenges, and futures of media literacy. Data & Society Research Institute. Retrieved from https://datasociety.net/library/the-promises-challenges-and-futures-of-media-literacy/

- Critical Media Project (n.d.). Media literacies. Retrieved from https://criticalmediaproject.org/media-literacies/

- Friesem, E., & Friesem, Y. (2021). Media literacy education in the era of post-truth: Paradigm crisis. In Research anthology on fake news, political warfare, and combating the spread of misinformation (pp. 589-604). IGI Global.

- Gerodimos, R. (2022) Media literacy, values, and drivers of youth civic engagement: Reflecting on two decades of research. In de Abreu, B.S. (Ed.), Media Literacy, Equity, and Justice (pp. 98-105). New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Hobbs, R. (2018, March 10). Freedom to choose: An existential crisis. Medium. Retrieved from https://reneehobbs.medium.com/freedom-to-choose-an-existential-crisis-f09972e767c

- Hobbs, R. ( 2017, January 10). Response to danah boyd's "Did Media Literacy Backfire?" [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqOvXv-wOUc

- Jenkins, H. (2020, October 26). Covid-19, participatory culture, and the challenges of misinformation and disinformation [Blog post]. Confessions of an Aca-Fan. Retrieved from http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2020/10/23/covid-19-participatory-culture-and-the-challenges-of-misinformation-and-disinformation?rq=misinformation

- Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T., & Liu, J. (2021). Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(2), 371-388.

- Kellner, D. and Share, J. (2007). Critical media literacy, democracy, and the reconstruction of education. In Macedo, D. and Steinberg, S. (Eds.), Media literacy: A reader, pp.3-23. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Literat, I. (2021). On research and hope, in an America aflame: sketching youth civic futures as a mother and a researcher, Journal of Children and Media, 15(1), 109-111, doi: 10.1080/17482798.2020.1858904

- Middaugh, E. (2019). More than just facts: Promoting civic media literacy in the era of outrage. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(1), 17-31.

- Mihailidis, P. (2018). Civic media literacies: Re-imagining engagement for civic intentionality. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(2), 152-164.

- NAMLE. (n.d.). NAMLE’s history. National Association for Media Literacy Education. Retrieved from https://namle.net/ about-namle/namles-history

- Rogow, F. (2016, December 4). If everyone was media literate, would Donald Trump be president? [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://medialiteracyeducationmaven.edublogs.org/2016/12/04/if-everyone-was-media-literate-would-donald-trump-be-president/

- Vahedi, Z., Sibalis, A., & Sutherland, J. E. (2018). Are media literacy interventions effective at changing attitudes and intentions towards risky health behaviors in adolescents? A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 67, 140-152.

- Wuyckens, G., Landry, N., & Fastrez, P. (2022). Untangling media literacy, information literacy, and digital literacy: a systematic meta-review of core concepts in media education. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 14(1), 168-182.